First International Polar Year was an edgy affair

During the first International Polar Year of 1882-1883, an American stole food from his comrades, and it wasn’t the first time. The act was all trip leader Adolphus Greely could stand. He ordered three other men, two with bullets in their guns and one with a blank cartridge, to aim at the chest of their comrade and pull the trigger.

“This order is imperative and absolutely necessary for any chance of life,” Greely wrote. His men carried out the command, and Greely’s scientific party, conducting a scientific mission in Canada’s high Arctic and starving on the retreat, was down to seven men. Two years earlier, when the group had set out for the Arctic, it numbered 25.

The first International Polar Year in 1882-1883 had a mission similar to the fourth, which began March 1 and extends to March 2009: An effort of scientists to monitor the Earth’s polar regions.

A lieutenant of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, Karl Weyprecht, thought up the first polar year. A polar explorer, Weyprecht argued that it was time to fill in the gaps of the map of the Arctic. Cartographers then drew Greenland with no northern boundary.

“Decisive scientific results can only be attained through a series of synchronous expeditions, whose task it would be to distribute themselves over the Arctic regions and to obtain one year’s series of observations made according to the same method,” Weyprecht wrote.

Weyprecht said previous polar expeditions became nothing more than polar highmarking, where explorers would try to reach the farthest north point without achieving anything more of scientific merit. Ironically, Greely also registered the farthest north spot during his first polar year expedition. His men, stationed at Lady Franklin Bay on Ellesmere Island, made it to 83 degrees north before bad times set in.

Greely’s station on northern Ellesmere Island was the farthest north camp of the 12 established during the first International Polar Year. The other American post was near Barrow. The leader of a schooner expedition to Barrow in the 1880s was U.S. Army Lieutenant P. Henry Ray, another explorer/scientist who would later leave his name in Alaska on the Ray River and Ray Mountains northeast of Tanana.

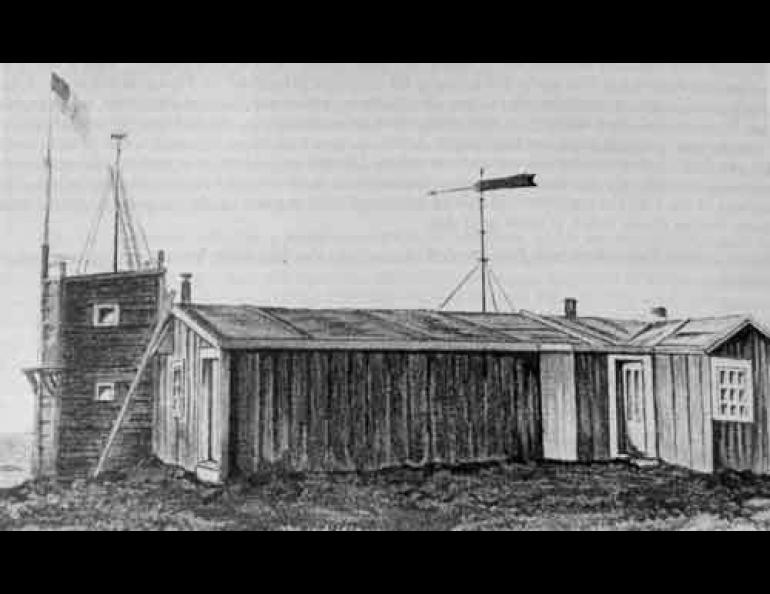

Ray established an observatory building near the site of today’s Barrow. Unlike Greely, Ray and his men had the good fortune of having open ice leads that allowed relief ships to bring them supplies during their two-year stay at the top of Alaska. Like many successful arctic explorers, Ray adapted his men to the ways of the Eskimos, once traveling with them by dog sled to an area around Prudhoe Bay.

“It is very doubtful if this vast stretch of country contains anything that will ever render it of any commercial value to the world,” Ray wrote in 1885.

After 27 months, including two winters in Barrow, Ray sailed back to San Francisco with all his men in good health. His expedition got little press because of the tragedy of “the reckless attempt to add something more to the cause of science,” as the Evening Telegram of St. John’s Newfoundland described Greely’s mission. Reporters overlooked the fact that Greely came back with two years of scientific observations.

“Collections from the station at Lady Franklin Bay were jealously guarded by Greely throughout his ordeal and brought safely back south,” wrote William Barr in “The Expeditions of the First Polar Year.”

Like Ray, Greely would also leave many footprints in Alaska after surviving the first polar year. He was head of the Army Signal Corps in 1900 when the corps strung telegraph lines from Valdez to Eagle and west to St. Michael at the mouth of the Yukon, a feat that would be tough to pull off today.