Grades keep slipping on Arctic Report Card

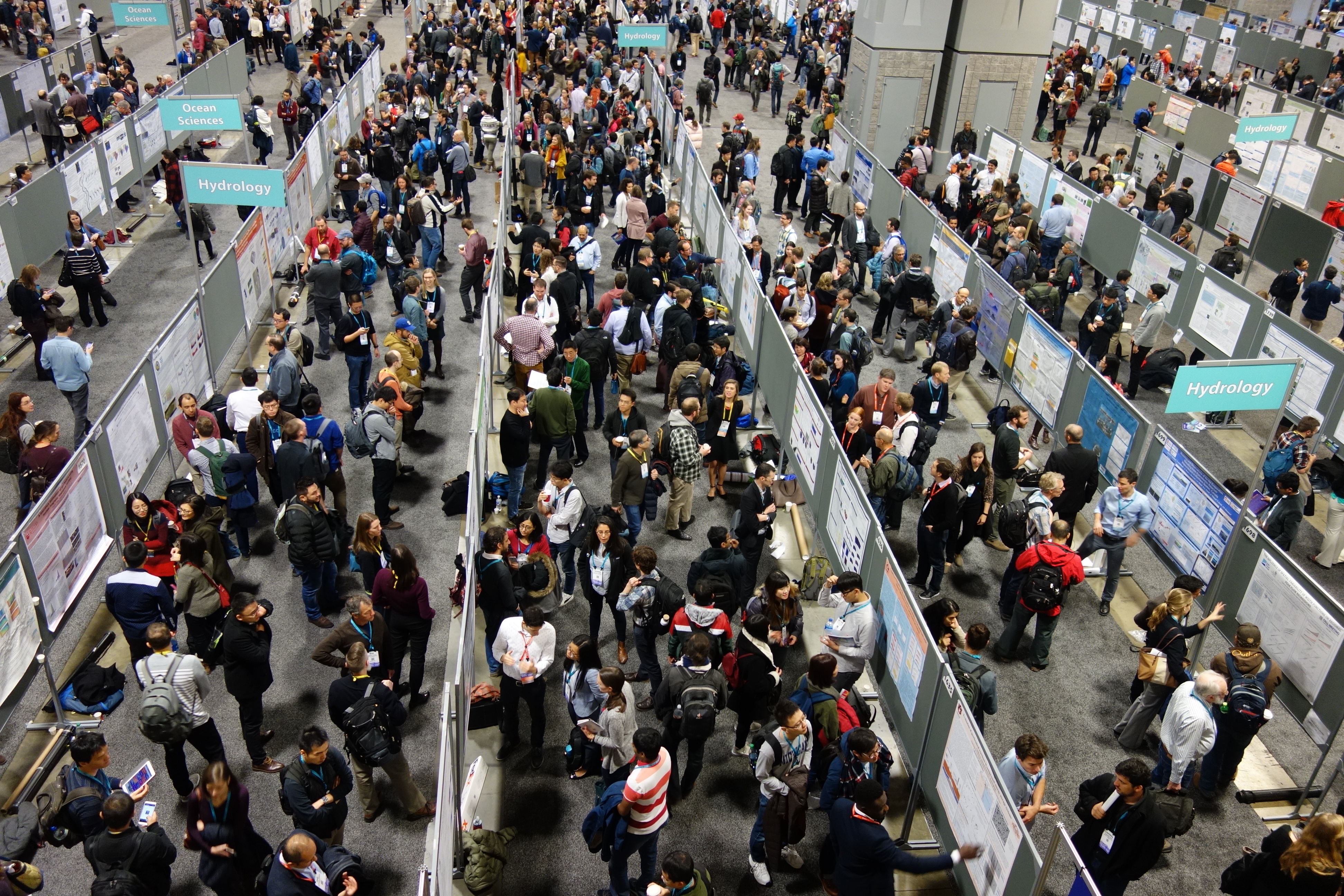

WASHINGTON, D.C. — At this annual gathering of thousands of scientists that has grown in step with the increasing number of people on Earth, researchers at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union again sounded the alarm for a quiet place — the top of the world.

At a press conference devoted to the changes in the Arctic, expert panelists spoke of dwindling northern sea ice, its probable connection with severe weather down here, decreasing caribou populations (with a notable exception in Alaska) and the discovery that the Arctic Basin has “a higher concentration of microplastics than anywhere else in the world.”

This was the 13th consecutive year of the December release of NOAA’s Arctic Report Card, a series of essays written by scientists.

Sea ice, which floats on the Arctic Ocean and is now expanding in sheets during the cold, dark polar night, has always been the leadoff topic of the press conference at AGU’s fall meeting.

This year, Don Perovich of Dartmouth College spoke of how thin that ice is over much of the Arctic Ocean, unlike a few decades ago when lots more of it survived the heat of summer. Now, sea ice constructed of slabs more than four years old makes up just one percent of the total ice cover.

Why does that matter? Younger ice is less likely to survive the heat of the summer. That means more open ocean on top of the world. That dark water absorbs heat from the sun that ice would have reflected away. More ice melts, and the Arctic becomes a less effective air conditioner for the rest of the world.

Perovich also noted the remarkable lack of sea ice in the Bering and Chukchi seas off the west coast of Alaska (a missing patch the size of Idaho) in early 2018. The ice extent there from a satellite image taken in late November 2018 is the lowest of the satellite era, since about 1978.

Less sea ice and the amount of heat it has introduced into the north has affected Alaskans from Utqiaġvik, where the local climate has changed to resemble that of a Scandinavian coastal city, to Fairbanks, where our above-zero winter seems more like Anchorage, where everyone now owns a pair of ice skates.

Just two caribou herds of 23 north of the Arctic Circle have been stable or increased from their maximum numbers, said Howard Epstein, an ecologist at the University of Virginia. The Porcupine Herd in Alaska and the Yukon and the Lena-Olenyk Herd in Russia are the only bands that don’t seem to be getting smaller. Populations of caribou and reindeer over the north have decreased from 4.7 to 2.1 million animals, possibly due to warmer conditions, he said.

Karen Frey of Clark University in Massachusetts spoke of tiny pieces of plastic now swirling in the salt waters of the Arctic. Microplastics — fragments of fishing gear, bottle caps, cigarette butt filters, elements of ship paints and other things — have been found all over the Arctic Basin.

In a 2018 study of 11 different fish species in the Bering and Chukchi seas, Chinese researcher Chao Fang found microscopic pieces of plastic in every one of more than 400 fish. Frey, a geographer and arctic specialist, said the plastic in northern oceans flows up on ocean currents.

“All roads in the global ocean lead to the Arctic,” she said.

The press conference room in Washington was filled with many of the same people who were there in 2006 on the same December day in San Francisco when the first report card came out. Including me. I did not need reading glasses then, nor did I have a daughter (who is now a pre-teen). But the message was the same and is even more convincing now.

“It’s one of the biggest global change signatures that’s undeniable,” said Jim Overland, an arctic researcher from the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle who sat in the audience for the packed press conference. “The signal is out of the noise these days.”

Overland is one of the scientists who initiated the Arctic Report Card 13 years ago, when the news from this conference was that computer models predicted the Arctic Ocean could be ice-free in summer by 2040.

“I’m one of the people who now think we’re looking at an ice-free summer by 2030,” Overland said Dec. 11. “I don’t see any reversal.”

Judging by the amount of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gasses we have already released into the atmosphere, the stage is set, Overland said. But there is a chance to turn things around.

“It’s going to take a lot of small steps, things like wind farms and better insulation in houses,” said Overland, who first visited the Arctic in 1968, when he drifted around on sea-ice islands used as study platforms when he was a student at the University of Washington. “We need to start now to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It won’t influence us, but it will greatly influence our grandchildren.”