Heating today with an idea from yesterday

With the rising price of heating oil, some people are looking to the past for ways to heat their homes.

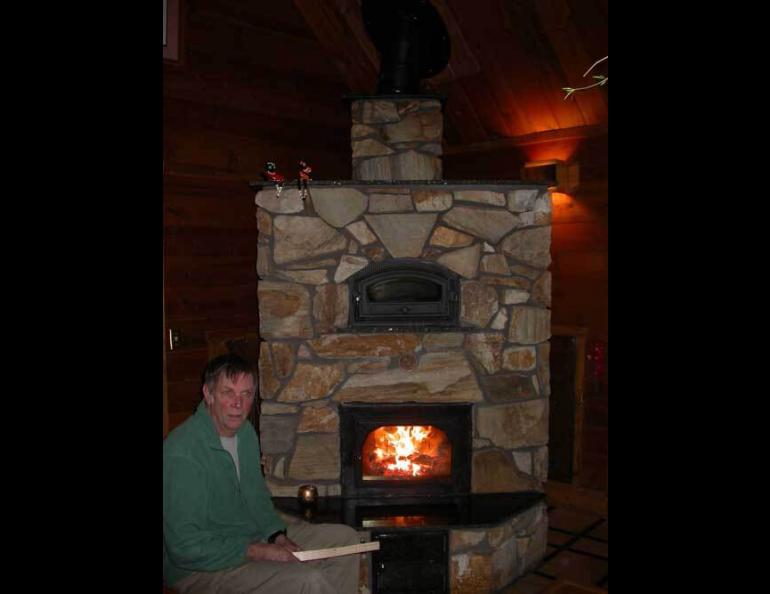

Masonry heaters, huge masses of stonework wrapped around a sinuous channel through which hot gases flow, are now appearing in Alaska homes. The clean-burning, efficient heaters existed for centuries in Europe and Scandinavia, but didn’t reach the shores of America until after the oil crisis of the 1970s.

Bill Reynolds and his wife Brenda Norcross of Fairbanks have heated their 1,400-square-foot house with a masonry heater for more than two winters. Reynolds said they have used two-and-one-half to three cords of wood per year to heat their home, which stays at a constant 70-to-72 degrees Fahrenheit in winter.

A masonry heater looks kind of like a traditional fireplace, but it fires like a wood stove, only faster and hotter. Reynolds fires his heater once a day if the temperature is warmer than minus 10 degrees Fahrenheit outside and twice if it’s colder. He stacks an armload of dry wood in the firebox and lights a golf-ball size piece of paper beneath the wood. Air drafted from outside his home gets the fire going like a blast furnace. After his wood disappears in about an hour, the stonework slowly releases the heat, warming the house for the next day or so. When he is firing the heater, the stovepipe leading from his house emits no smoke, just squiggly air distorted by heat.

Reynolds, the owner of Solutions to Healthy Breathing, a company he designed to improve the air quality of peoples’ homes, said his wife has asthma, which made it difficult to use a traditional wood stove.

“In two years (of using the masonry heater), she’s had no (asthma) attack,” he said. “I couldn’t open a wood stove door in the past.”

He likes the heater for other reasons, too.

“Not only is it efficient, it’s a clean way to heat and it’s a work of art in your home,” Reynolds said.

Dan Givens of Stonecastle Masonry in Ester built Reynolds’ masonry heater, and he has built 27 others. When called on his cell phone recently, Givens answered from a large Fairbanks home in which he and a partner were installing two masonry heaters.

Dave Misiuk, the Wood Energy Specialist at the Cold Climate Housing Research Center in Fairbanks, said more people are stopping in all the time to see the masonry heater just inside the entrance to the center. Givens also built that one.

“A lot of young couples are coming in, thinking of designing their houses,” he said.

Masonry heaters are so large (typical models weigh from 4,000 to 12,000 pounds) that it is often easier to build houses around them than to add them to existing homes, said Misiuk, who designed his own house with a masonry heater in the center and an open floor plan.

Europeans historically used smaller masonry heaters to heat portions of their homes while closing off certain rooms during the winter, Misiuk said. Americans tend to want larger masonry heaters that can heat the entire home, but Misiuk said he sees masonry heaters as “a really good component of an integrated heating plan” that would also include a back up heat source and possibly other renewable energy systems.

Because they burn so hot (with the stonework remaining cool enough to touch), masonry heaters are extremely clean and are among the most efficient ways to get heat from cordwood. They are also expensive (Givens has charged between $8,000 and $20,000 for his masonry heaters), and materials for them are spendy even for do-it-yourselfers.

“The refractory concrete for the firebox sells for $22 a bag in the Lower 48, but costs $117 a bag up here,” Misiuk said.

The Cold Climate Housing Research Center is now sponsoring a design contest to make masonry heaters viable for more Alaskans.

“We’d like to try and create a more affordable masonry heater for Alaska,” Misiuk said.