High-altitude ice core reveals secrets of Alaska's past

China may be fertilizing Alaska.

Some of Alaska’s high mountains might have been ice-free as recently as 1000 B.C.

Mount Churchill might not be the source of two immense volcanic eruptions that left blankets of ash over eastern Alaska.

These are some of the curiosities emerging from ice cores pulled from a high saddle in the St. Elias Mountains in eastern Alaska. In summer 2002, Lonnie Thompson of Ohio State University completed a mission to drill ice from a platform 14,500 feet above sea level in a pass between Mounts Bona and Churchill.

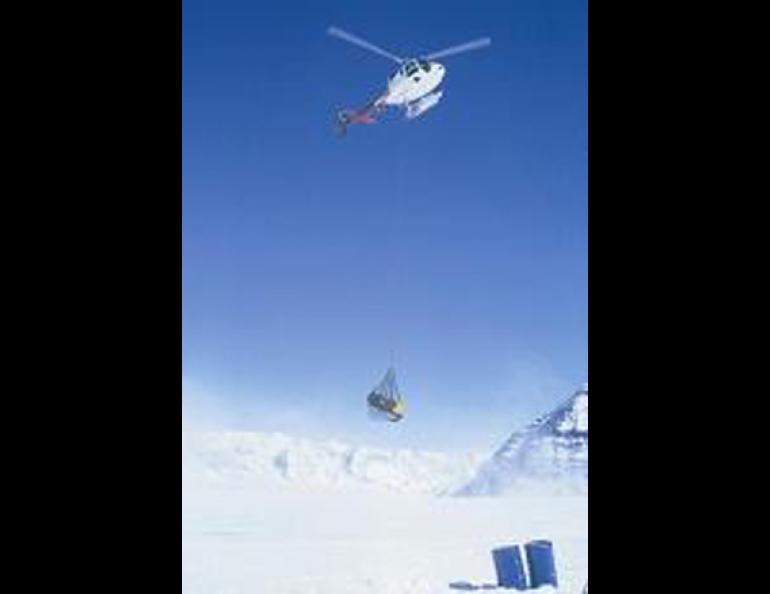

Two summers ago, Thompson and his crew trucked six tons of drilling equipment from Columbus, Ohio to Chitina, Alaska. With the help of a helicopter piloted by Lambert DeGavere of ERA Aviation and a turbo Otter piloted by Paul Claus, they returned home with 10 tons of freight, including more than one-quarter mile of Alaska ice. Within that ice is a record of what floated in Alaska air during the last 2,500 years.

Thompson and his colleagues set a record for deepest ice core retrieved from a mountain when they drilled 1,500 feet through the ice down to solid rock on Bona-Churchill. Within that core are layers that represent each year of snowfall at the spot, which has remained below freezing for thousands of years.

“It turned out to be a marvelous record,” Thompson said. “It’s probably the longest annually resolved record ever to come out of a mountain range.”

Thompson, who has drilled ice cores on lofty sheets of ice from Africa to Antarctica, reports three intriguing results from the Bona-Churchill ice core, which he and his colleagues are still interpreting. One was the relative absence of the “White River ash,” a thick layer of volcanic ash found all over eastern Alaska and the Yukon Territory. Geologists have traced the ash to large eruptions in the Wrangell-St. Elias mountain ranges in about A.D. 180 and A.D. 700, and some pointed to Mount Churchill as the source. Thompson came to Alaska armed with special drill bits designed to penetrate several feet of ash, but the drill bits only pulled up ice.

“Could you have an eruption of that size 500 meters away (from the drill site) and not see any evidence of it?” Thompson said.

The temperature of the ice, minus 3 degrees Fahrenheit (-19.8 C) at 1,500 feet below the surface, is another clue that Mount Churchill might not be the source of the White River ash. The mountain would probably be warmer if such large eruptions happened there, Thompson said.

A second surprise in the Bona-Churchill ice core is the high level of potassium found in snow layers from the 1960s.

“Potassium is not something you usually find in an ice core,” Thompson said.

His guess is that the potassium is from China, where wind lifted it from fertilized dry fields and carried it across the Pacific to settle in Alaska and elsewhere in North America. Thompson said he doesn’t know if the level of potassium is high enough to boost the growth of Alaska plants.

A third question raised by the Bona-Churchill ice core is why the ice from 1,500 feet down in the core fell as snow in 1,000 B.C., which suggests that no ice existed on the mountain before then. The current theory of Alaska’s past is that glaciers have covered at least the mountainous parts of the state for at least 12,000 years, when the last Ice Age started to wane. Though Thompson said volcanic heat might have affected the Bona-Churchill ice core, it shows no evidence of this.

“Is it possible that the ice totally disappeared, and these glaciers are a function of climate in the last 5,000 years, in the cooling period that started in the middle of the Holocene (the last 11,000 years of Earth’s history)?” Thompson said. “To me, it’s a very important story to unravel.”