If a mountain fell in the Alaska wilderness . . .

Jackie Caplan-Auerbach was checking earthquake activity at Alaska volcanoes from her Anchorage office on September 14th, a routine she performs every day at the Alaska Volcano Observatory, when she noticed a strange seismic signal on Mount Spurr.

A large shock to the earth—not as abrupt as an earthquake—had happened somewhere in Alaska. When Caplan-Auerbach saw the odd signal was even stronger on Mount Wrangell, she suspected there was a great avalanche somewhere in the restless corner of Alaska where the panhandle of Southeast meets the rest of the state.

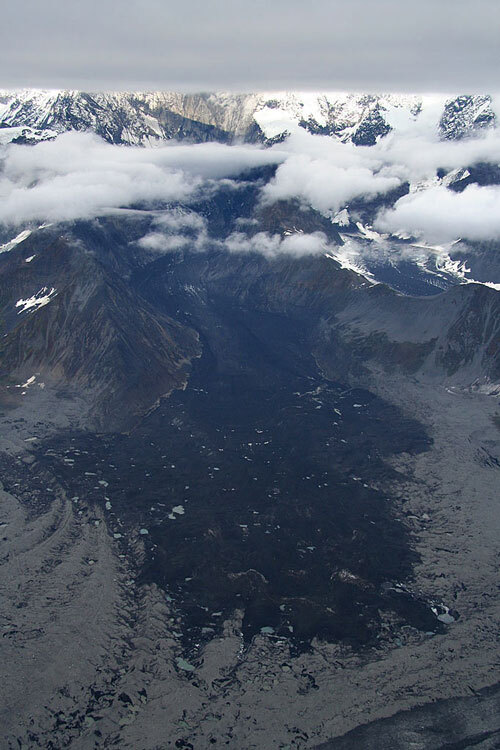

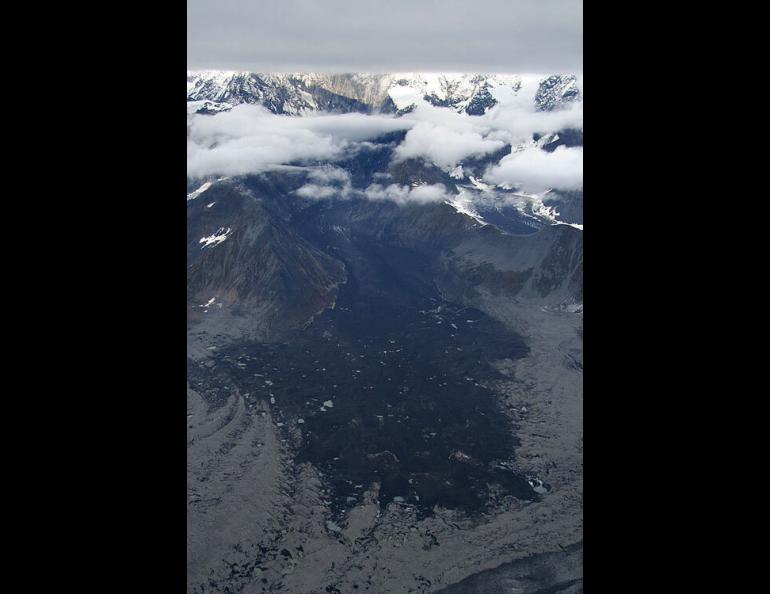

There was. A good chunk of Mount Steller, a razorback 10,000-foot peak about 80 miles east of Cordova, had collapsed onto Bering Glacier. Rocks and ice from the mountain tumbled 8,000 vertical feet, spilling out in a chunky black delta that reached six miles from the mountain. Christian Huggel, a Swiss avalanche specialist who happened to be visiting the Alaska Volcano Observatory in Anchorage, estimated that the amount of rock and ice that shook loose was equal to a pile one mile long, one-third mile wide, and 50 yards high.

Caplan-Auerbach studies avalanches on Iliamna Volcano, but the largest recorded avalanches there are about one-fifth of the size of the recent event at Mt. Steller.

“We’ve seen big ones, but we’ve never seen them generate seismic signals like this,” she said. “It’s a monster.”

Scientists at the Alaska Tsunami Warning Center in Palmer also noticed the avalanche when it happened. They called the Alaska Earthquake Information Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks to confirm.

“It showed on all our instruments on mainland Alaska,” Natalia Ruppert of the earthquake information center said, adding that the amplitude of the event was about equal to a magnitude 3.8 earthquake, and more than 200 seismometers all over the state picked up its vibrations.

Scientists who monitor infrasound waves—signals with frequencies too low for humans to hear, generated by blasts from underground nuclear bombs and winter storms in the Gulf of Alaska, among other sources—also detected the avalanche from Fairbanks, 330 miles away from Mount Steller.

“It was a nice big signal here,” said Daniel Osborne of UAF’s Geophysical Institute.

Sometimes large earthquakes trigger massive avalanches, as happened in 2002 when the Denali Fault earthquake shook acres of rocks over Black Rapids and other glaciers, but Mount Steller broke for reasons unknown.

“It’s one of those big puzzles,” Caplan-Auerbach said. “A lot of these (steep mountains) probably sit right on the verge of failure.”

In her studies of Iliamna Volcano, Caplan-Auerbach has found that avalanches like the one on Mount Steller sometimes rumble one-half hour to two hours before they collapse, possibly due to the fracturing of ice at the base of the avalanche material. She just submitted a paper on the curious tendency of some avalanches to move before they collapse.

“I don’t think anyone’s ever seen avalanches that give warnings,” she said.

One of the unique features about the giant avalanche of September 14, 2005 on Mount Steller was that perhaps no one saw it or felt it. The nearest settlements, tens of miles away, were too far for people there to feel the rumbling.

“It shows how wonderful Alaska is,” Caplan-Auerbach said. “Places like Iliamna could break in half and nobody would be killed.”