Killer whale calls altered by whale-watching boats

Killer whales of the Pacific may be changing their tunes in response to the noise from whale-watching boats.

Scientists from the University of Durham in England studied three groups of killer whales off the coast of Washington state and found that the whales lengthened a call by about 15 percent when whale-watching boats were near. In earlier studies, scientists had documented changes in humpback whale songs due to sonar signals and birds that sang at higher pitches near heavy traffic, but the killer whale study may show the first animal reaction to a certain threshold level of noise. Studies of earlier periods of whale-watching activities with fewer boats did not show that orcas changed their call lengths.

Killer whales live in groups, called pods, which consist of females and their offspring of both sexes. The young whales may remain with their mother for 30 years or more. Each pod has a series of calls, and scientists have noticed that these calls remain the same for decades or longer, and each pod seems to have a favorite call.

The scientists—Andrew Foote and Rus Hoelzel of the University of Durham and Richard Osborne of the Whale Museum in Friday Harbor, Washington—studied three pods off the coast of Washington. One pod’s primary call sounds like a train whistle, another is like the mew of a kitten, and the third pod’s favorite call sounds like a slide whistle. They compared recordings of calls from the different pods both with and without boats present in three time periods—from 1977-1981, 1989-1992 and from 2001-2003. They found no difference in the length of the calls from any pod that was in the presence of boats during the first two periods, but from 2001-2003 all three pods whistled calls that were 15 percent longer when boats were around.

The researchers pointed out that the average number of whale-watching boats increased almost five times from 1990 to 2000. Of a current fleet of about 72 commercial whale-watching boats in Puget Sound, an average of 22 followed killer whale pods during daylight hours. Because of the apparent change in whale behavior with an increased number of boats, the researchers suggested that there might be a level of underwater noise that forces the orcas to lengthen their songs to communicate, much as a person has to yell to be heard in a noisy place.

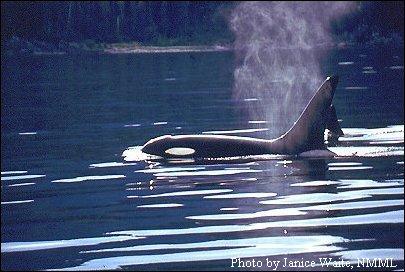

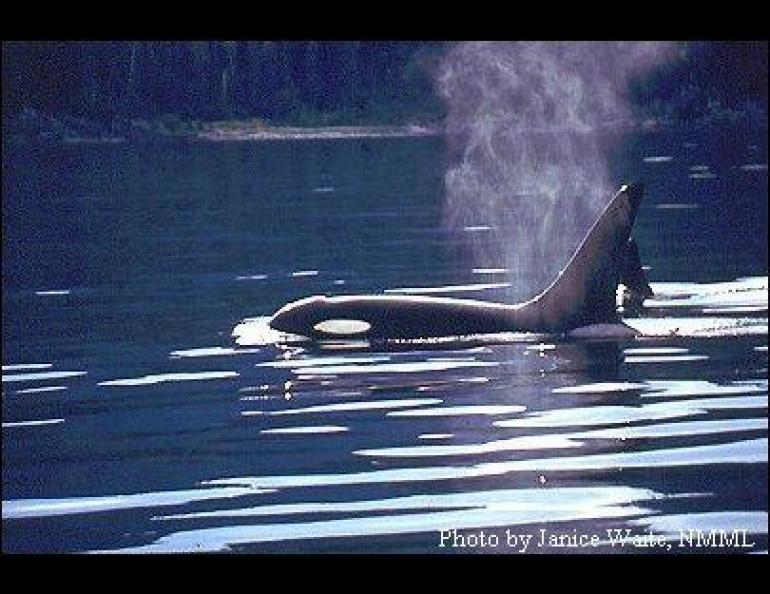

The killer whale is not a whale but really the largest member of the dolphin family. Found in all the world’s oceans and seas, killer whales can be seen in Alaska’s waters in places like the Inside Passage, Prince William Sound, the Kodiak archipelago, and Glacier Bay and Kenai Fjords national parks. Recently, researchers have questioned whether killer whales have been responsible for declining numbers of sea otters and Steller sea lions off the coast of Alaska. The top predator in Earth’s oceans probably uses its calls to communicate, and the interference caused by the noise of boat engines might compromise that ability. Even so, the British researchers are not against the practice of whale watching.

“Whale watching helps to promote conservation, and gives the public a rare opportunity to observe this impressive animal in the wild,” Hoelzel wrote in an email message. “Like any similar activity, we need to ensure that we do it in a way that avoids harming the subjects of our attention.”