Largest earthquake on the planet, until proven otherwise

What’s this? Another aftershock?

That’s hundreds now, each more faint than the last.

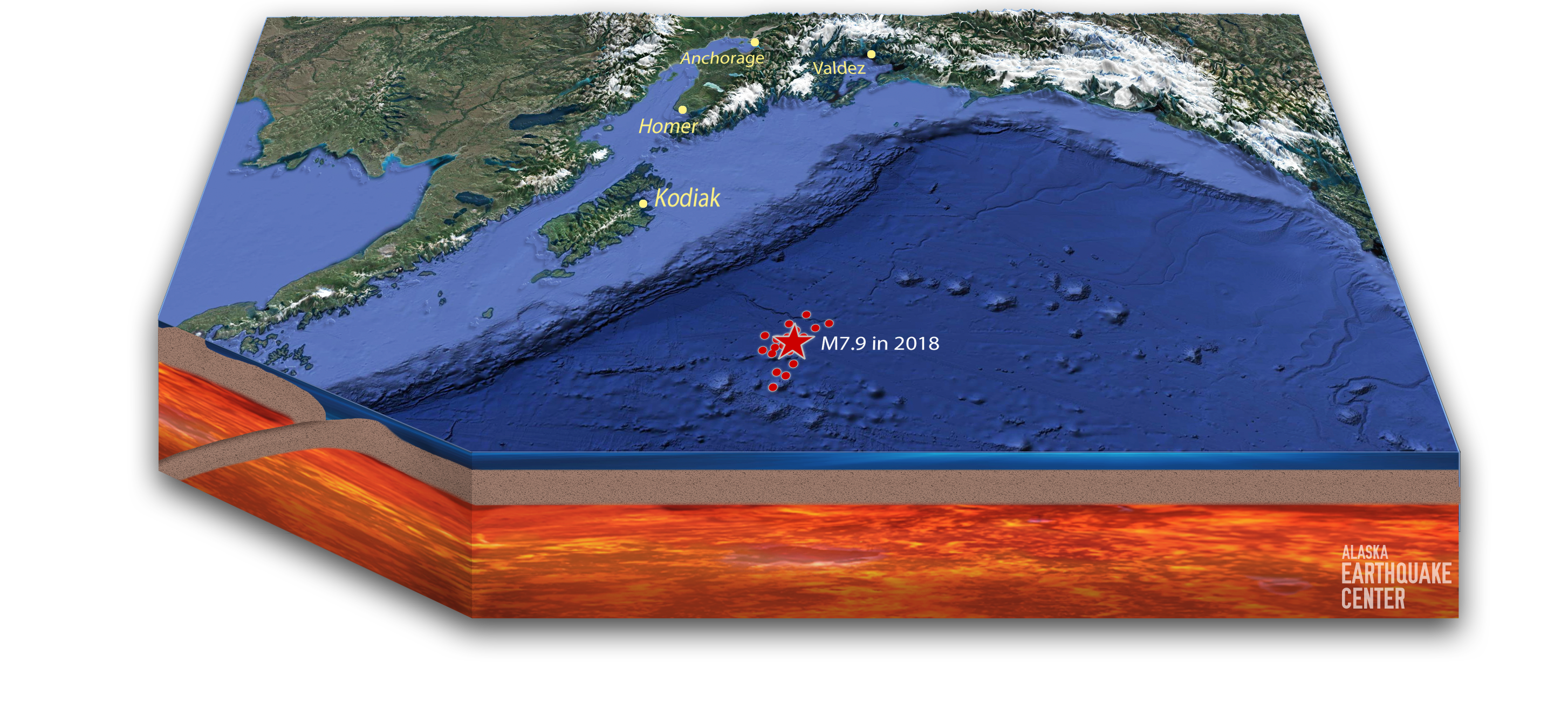

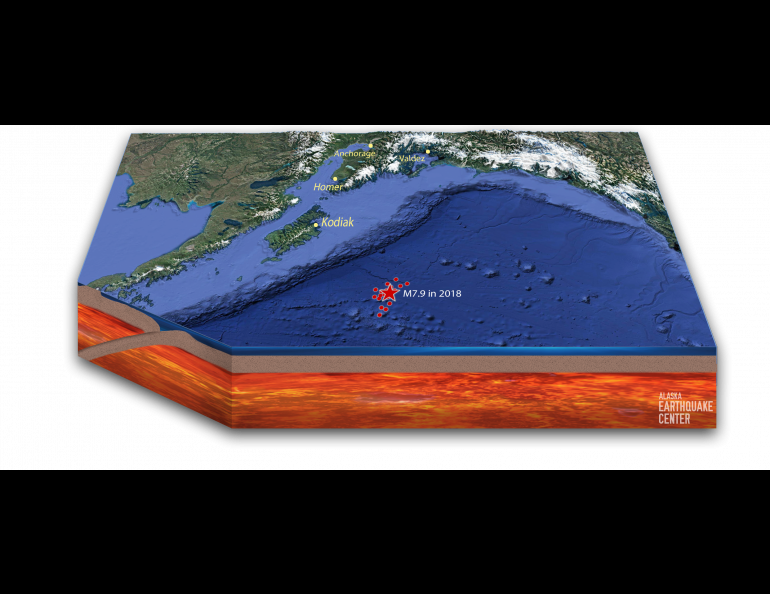

Sorry, I guess I’ve moved on. I should pay more attention, given that you — a 7.9 deep in the seafloor not far from Kodiak — are the most powerful earthquake on the planet since one off Mexico last August.

It’s just that you’re so mysterious, hard to define. And you got buried in my news feed.

But you did create a stir. You rousted hundreds of Alaskans. People felt the shake, saw alert messages on their phones. Feet hit the floor. They grabbed what they could and drove to high places.

The all-clear came two-and-a-half hours later, when your harmless waves lapped at Sitka, 530 miles away, earlier than they reached Kodiak, 180 miles away. This proved again that tsunamis travel faster in deeper water, and the abyss lurks just beyond the Continental Shelf.

A few who study tide gauges and buoys saw the bumps. The largest wave, which arrived at Homer, was less than a foot high.

You didn’t generate a massive wave because you did not shove the seafloor toward the sky. You were more like two freight trains passing too close, grinding past one another, flashing sparks and smelling of burned metal.

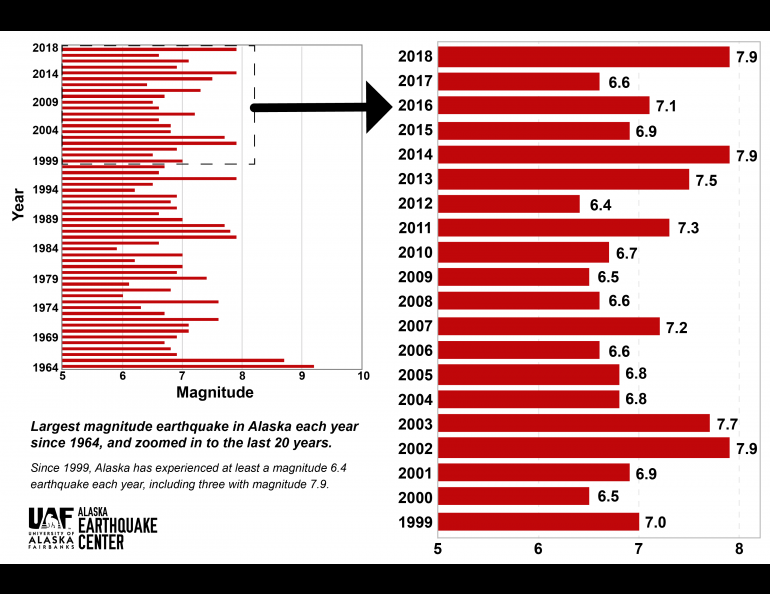

There’s no argument, a 7.9 is impressive. Even in Alaska, we’ve felt only three in the last 20 years. Each of them was 15 times more powerful than the 7.1 Iniskin earthquake that in 2016 snapped gas lines in Kenai and burned down four houses.

One of those 7.9s was a celebrity: the 2002 Denali Fault earthquake. The third, kind of like you, was distant, bashful. That one struck three years ago, deep beneath the far Aleutians, swaying the rusted anti-aircraft guns on Kiska. Like you, it did not kick away masses of water or leave a scar.

The Denali Fault earthquake ripped a 200-mile frown across the middle of Alaska, shaking people out of their daily routines and snapping the frozen asphalt of two roadways.

Scientists called it once-in-a-lifetime. Compared to you, the Denali Fault was easy to study. Drive down the Parks Highway, hike a few hundred steps off the road. Set up seismometers and GPS units.

A month after it shook Alaska, the Denali quake had its own session at the earth-science conference in San Francisco. For a few hours during a poster session, white-haired scientists nodded and smiled. Thirty years earlier, they recommended setting the Trans-Alaska Pipeline on long rails, right above where they had seen ancient wounds in the ground.

There in the Alaska Range, they found a weak splice in Earth’s crust cutting across the pipeline’s path. The rails allowed the pipe to skitter sideways 60 feet on its Teflon shoes. The pipe almost walked off the beams, but it did not snap.

But you — what the seismologists are calling the Offshore Kodiak Magnitude 7.9 Earthquake — were pretty much invisible, 12 miles beneath the inky ocean, 180 miles from land.

You came just after midnight. If the skipper of a pollock trawler was drifting above at 12:31 a.m. January 23, he sensed nothing unusual: Frothing green waves, no lights on the horizon. Darkness, pitch and roll.

To the surprise of seismologists who blinked at their phones and saw the number 8 (soon after adjusted to 7.9), you were not centered on the great suture at the bottom of the sea. Too far south. Too far east.

The Aleutian Megathrust, the underwater arc where the Pacific Plate bulls beneath the North American Plate on which we sit, was the logical place for an earthquake of your stature.

But you were 100 miles away, bursting on the Pacific Plate well before it dives beneath the continent. By far the largest of 3,000 earthquakes detected in Alaska so far this year, you are the most enigmatic.

An earthquake of magnitude 7.9 most often leaves a mark, more than 100 miles long, oddly straight. You were a “complex rupture,” the result of crisscrossing weak spots in the earth failing within seconds of one another.

“It’s a mess of a fault system,” said seismologist Stephen Holtkamp, who with his colleagues is still trying to make sense of you. Two days after his eyes popped open after midnight, he spoke at a lunchtime debrief at the Alaska Earthquake Center, part of the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Though you are a puzzle, one thing is obvious: You have a much gentler character than the famous March 1964 earthquake that shattered the megathrust a few hundred miles away. During that magnitude 9.2, the Pacific Plate lurched under the North American Plate, tearing and lifting and dropping and throttling, for a terrible four minutes. Predictable and rogue waves leapt from the deep, raced to shorelines. Within six hours, a dozen people died in California.

But you are not the Great Alaska Earthquake. People don’t appreciate what you did, ringing the planet like a hammer striking a keg of beer. But your waves, flowing through liquid earth, stirred a rocky pool 2,000 miles away in the Nevada desert. You caused a sieche, standing waves in a calm body of water. In the turbulence, within Devil’s Hole, part of Death Valley National Park, male pupfish flashed blue, their spawning color.

Maybe you are weird enough that you will live on longer than the Rat Islands 7.9 of 2014. You just released pressure on a portion of the great megathrust. You also added stress to other segments, possibly shaving a few years off the interval between 1964-strength earthquakes.

I’m sorry I lost interest. Forgive me. But don’t forget: This year, until some desert shrubland or undersea canyon fractures with a magnitude 8.0 — something that happened only once in 2017 and not at all in 2016 — you are still No. 1.