Life on ice, two miles thick

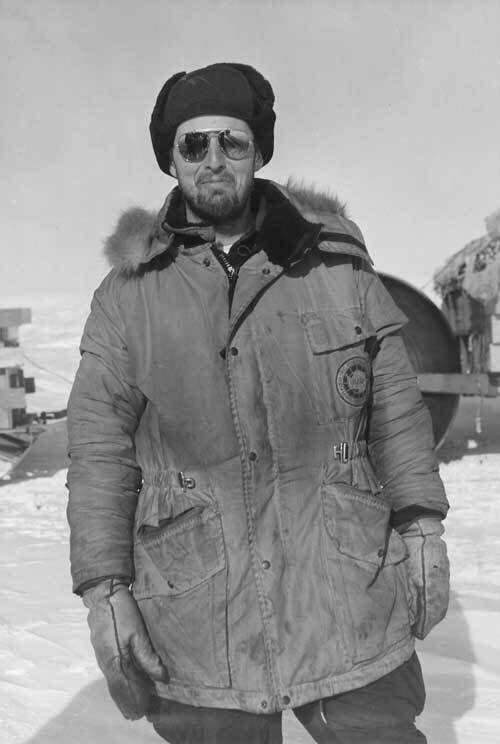

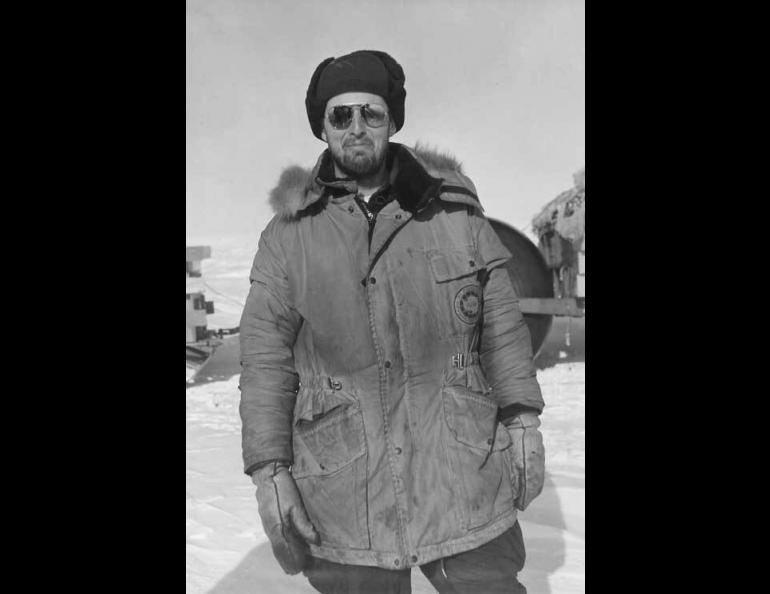

Fifty years ago, Charles Bentley and five other young men chugged across the ice of Antarctica in three tracked vehicles, exploring the mysterious white continent. In those days when frontiers existed on the planet, Bentley and his comrades saw a mountain range ahead of them that had Rocky-Mountain-size peaks with no names.

“We were the first ones to see almost all those mountains,” Bentley said during a recent trip to Fairbanks. “We were traveling about 24 miles a day, and we thought each day, ‘tomorrow, we’ll get to the mountains.’ But they were 200 miles away. It was quite a sight to watch these magnificent mountains gradually come up on the horizon.”

He and his traveling companions gave a few of the peaks their names, which remain on today’s map

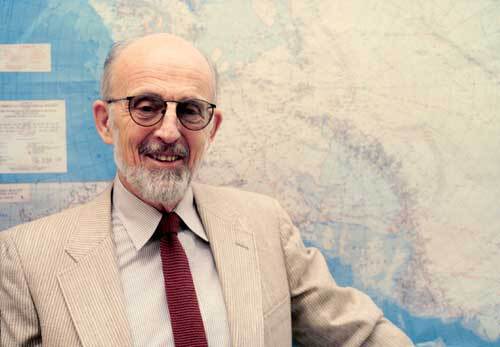

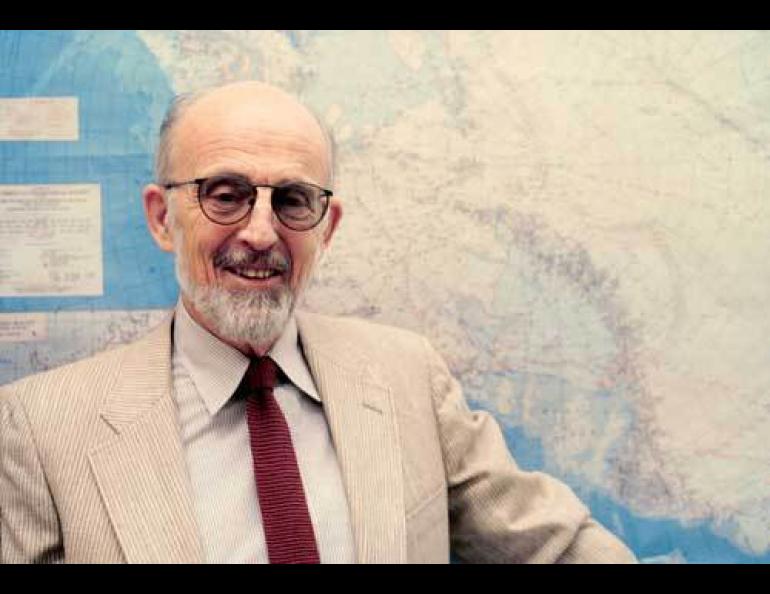

“I thought we were playing a joke (naming the mountains after themselves),” he said. But the names stuck. Bentley, now 78 and a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, now has two features named after him in Antarctica: Mount Bentley, about 14,000 feet above sea level, and the Bentley Subglacial Trench, 8,327 feet below sea level, the lowest point on Earth’s surface not covered by ocean (because ice fills it). Mexico could hide in the under-ice canyon that bears Bentley’s name.

“I claim to be the only person with a hill and a hole named after him,” Bentley said.

During that first traverse across Antarctica in 1957, Bentley and his partners made another discovery, perhaps more startling than the unknown mountain range—in some areas, Antarctica was so thickly covered with snow and ice that it was two miles down to bedrock.

“The general belief at the time was that all of West Antarctica was a mountainous land (covered by snow and ice), and that as soon as we got off the ice shelf, the mountains would come up,” Bentley said. “Instead, (the bedrock level) went down, and was thousands of meters below sea level. That was totally startling.”

The researchers made the discovery by drilling holes in the ice, dropping in a pound of explosives, and seeing how long it took for the seismic signal to return from bedrock. Up to three miles thick in places, ice burdens the “isostatically depressed” continent so that if it melted, the land beneath would rise about 1,500 feet. The thickest ice on Antarctica—and in the world—is about 15,700 feet thick.

Bentley was so intrigued with the extent of the ice that he signed up to stay in Antarctica another season. Fifty years later, he has since evolved into one of the world’s experts on the continent, and he is still traveling there, having returned this January as part of a University of Wisconsin team. Bentley has stood on Antarctica in six consecutive decades. And what changes has he noticed in that time?

“Marvelous old planes from the ‘30’s are still flying around,” he said. “And field camps always seem to have good cooks, just like they used to . . . The ice changes are too large in scale to see. By inspection (from the ground), you’re never going to see any differences.

“Changes in the ice sheet may be hard to see, but they are measurable and they are accelerating, contributing to global sea-level rise,” he said. “The world ignores Antarctica at its peril.”