Listening to the voices of killer whales

In the deep blue ocean just off the coast of Alaska, killer whales are now communicating with one another with clicks and whistles. Scientists are hearing them.

Hannah Myers has listened to many hours of orca calls in the Gulf of Alaska. The University of Alaska Fairbanks graduate student often knows a killer whale’s family group after hearing just a few syllables of its call.

Using hydrophones (underwater microphones) lowered into saltwater entrances of a few iconic Alaska bays, Myers has found that killer whales are present even in winter, something scientists did not know before.

Myers’ year-round listening complements decades of work by Dan Olsen and Craig Matkin of the nonprofit North Gulf Oceanic Society based in Homer. Olsen and Matkin have long studied killer-whale diets, have identified individuals with photos and have documented the damage done by a leaking oil tanker.

After joining Olsen and Matkin’s team in 2019, Myers has developed a great appreciation for the creatures whose echoes and squeaks she hears in her headphones. Killer whales are somewhat like humans in a few ways:

* Orcas live to about the same age as people, with females living longer than males.

* Their body temperature is the same as yours and mine.

* Female killer whales undergo menopause.

* Killer whales often form pods, family groups led by mother whales that can include their babies, those babies’ babies and even great-great grandwhales.

Scientists describe killer whales as “cosmopolitan,” meaning they can be found in just about any ice-free ocean on Earth, though most live in colder waters. At least 50,000 of the sleek black-and-white mammals are jetting through salt water today.

Swimming off Alaska’s southern coast are three distinct groups of killer whales that are almost identical to the eye but have likely not bred with each other for hundreds of thousands of years.

Scientists call the first of these killer whales residents. They eat mostly salmon, preferring chinooks. Residents are the orcas in stable social groups led by females.

Transient killer whales eat seals, sea lions, porpoise and other marine mammals. Myers’ sound recordings have included the voices of seven transient killer whales that are the only surviving whales of a group devastated by effects of the crude oil released by the Exxon Valdez in 1989. The seven remaining are from a group that had at least 22 members before that event.

Offshore killer whales, found in the deep ocean away from the coast, eat sharks, especially Pacific sleeper sharks, with a fondness for their livers.

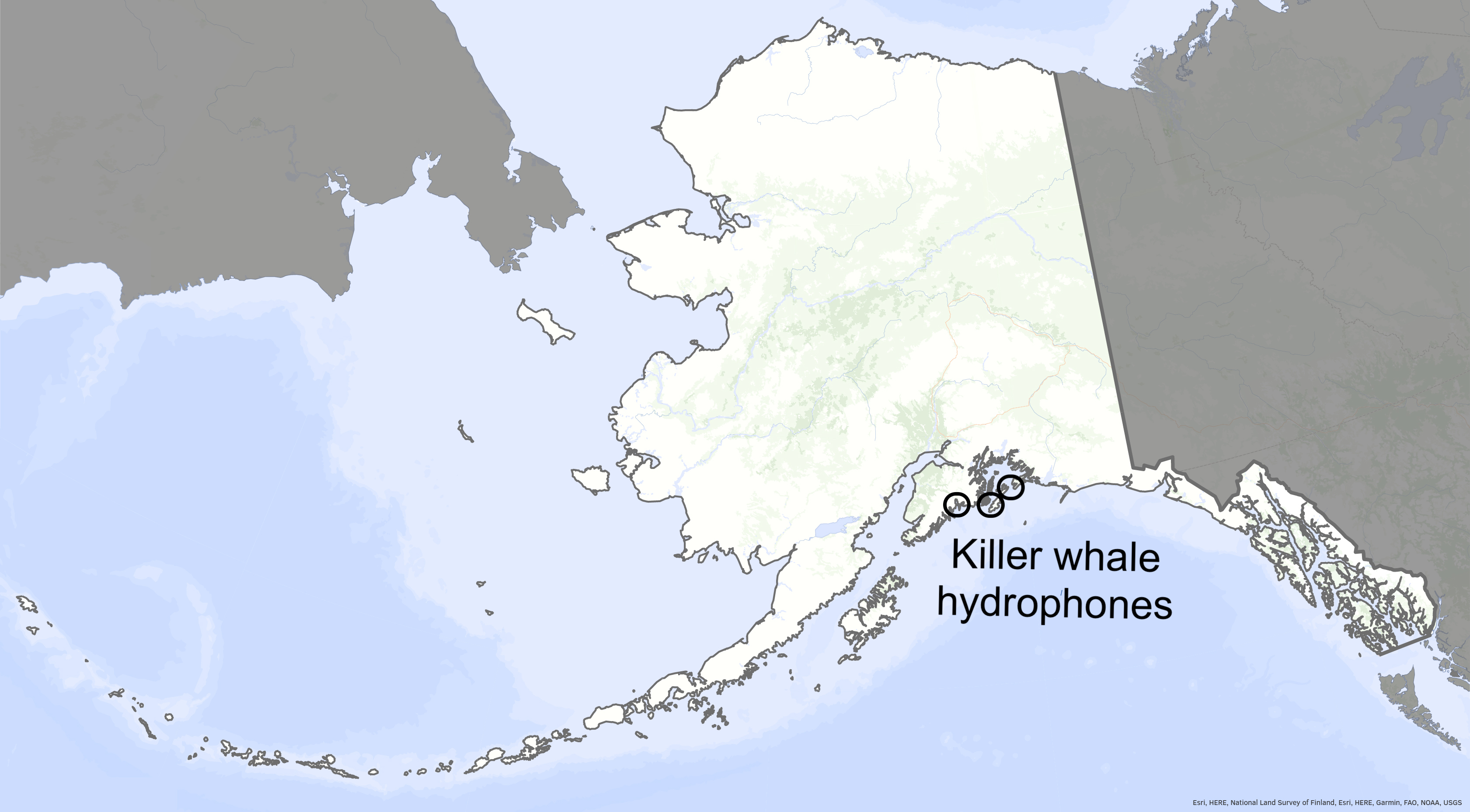

To learn more about the distribution of all three of these orca groups throughout the year, Myers deployed hydrophones at three locations in the northern Gulf of Alaska: at the head of Resurrection Bay, which leads to Seward; at the entrance to Montague Strait in western Prince William Sound, and at Hinchinbrook Entrance, farther east in Prince William Sound.

The hydrophones, which Myers and the North Gulf Oceanic Society team recover once each year with a grappling hook or by diving for them, are suspended about 10 feet above the sea floor. The instruments can detect a killer whale’s vocalizations from up to 15 miles away. The whales use clicks for echolocation just like bats, whistles for short-range communication and repeated calls that are unique to a group.

She has also heard eerie humpback whale calls, rain splattering on the ocean surface, waves crashing during storms and the noise of our species.

“Boat engines are extremely loud, even in a relatively pristine environment like Prince William Sound and Kenai Fjords,” Myers said.

The thrum of an oil tanker’s engines might interfere with killer whales’ ability to communicate or echolocate. Myers’ team’s results may help people help the federally protected orcas, such as by requiring ship captains to throttle down to reduce engine noise.

Myers’ fieldwork, executed on a 34-foot vessel that sails out of Seward, is shedding light on the undersea world off the south coast of Alaska. She is eavesdropping under the surface to help protect the top predator of the world’s oceans.

“We at least need to know where they are,” she said.