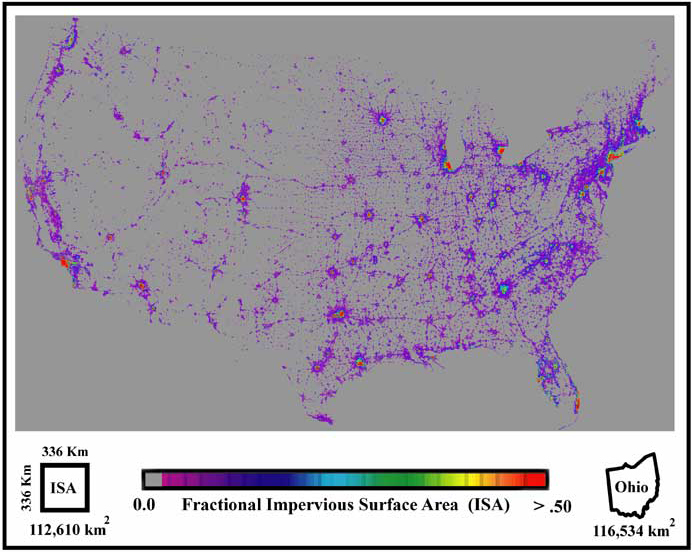

Lower 48 development footprint larger than Southeast

Researchers added up all the concrete, paved roads, buildings and other manmade hard surfaces in the Lower 48 and found a combined area of nearly 44,000 square miles, about the size of Ohio. That’s enough pavement, concrete and shingles to cover the combined areas of Southeast Alaska and Kodiak Island.

“I was surprised it was as big as Ohio, but a lot of people thought it’d be the size of Texas,” said Chris Elvidge, the main author of the study and manager of the Nighttime Lights Lab at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Geographic Data Center in Boulder, Colorado.

Elvidge and his coworkers use satellite data to produce maps of lights across North America, which is one of the inputs that helped them determine the “impervious surface area” of the Lower 48 states. The scientists didn’t include Alaska or Hawaii in their study, but will in a project they are now working on—a map of the developed areas of the entire world.

Elvidge and others produced the map of the contiguous states to see how urban sprawl is affecting the planet’s budget of carbon, a greenhouse gas when in the form of carbon dioxide.

“As you add pavement, buildings and sidewalks, you are decreasing the area that can have vegetation,” Elvidge said. “With that, you’re decreasing the uptake of carbon by plants.”

Ironically, there are some cases where the paving of America results in an increase of plants that take up more carbon dioxide, Elvidge said. Golf courses and lawns in some desert communities have changed the carbon balance there.

“Phoenix is like an oasis with a barren desert around it,” he said. “In some cases, lawns take up much more carbon than the original vegetation that would have been there.”

The transformation from wilderness to city has also created “heat islands,” where blacktop and heat-absorbing shingles make cities warmer than the surrounding countryside. Los Angeles, for example, is about 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than areas around it. Even Fairbanks is a heat island, with winter temperatures downtown up to 20 degrees warmer than outlying areas.

Elvidge said scientists who study Earth’s carbon equation are not the only ones who are interested in the new map of the U.S.’s non-absorbent surfaces. Hydrologists want the information to help them model flood potential. Other groups use the nighttime lights data to detect large fires, to monitor activity in fisheries where fishermen use bright lights to attract fish, to check where people are burning natural gas flares off oil wells, to find the best place is to set up a telescope for star gazing, and even to locate good habitat for sea turtles, which thrive on beaches with little or no artificial light.

When the worldwide map of impervious surfaces is complete in about three years, Elvidge said he expects to find a few countries with a higher percentage of developed land than the U.S.

“One I’m sure of is Singapore,” he said. “And maybe some European countries.”

He and his colleagues are sure of another thing—that America’s hard shell will continue to grow each year, with an accompanying three million more people, one million new homes built, and 10,000 additional miles of roads.