The man who broke through the Northwest Passage

Fifty years ago, a ship long as the Empire State Building sailed toward obstacles that captains usually avoid.

The icebreaking tanker Manhattan was an oil company’s attempt to see if it might be profitable to move Alaska oil to the East Coast by plowing through the ice-clogged Northwest Passage.

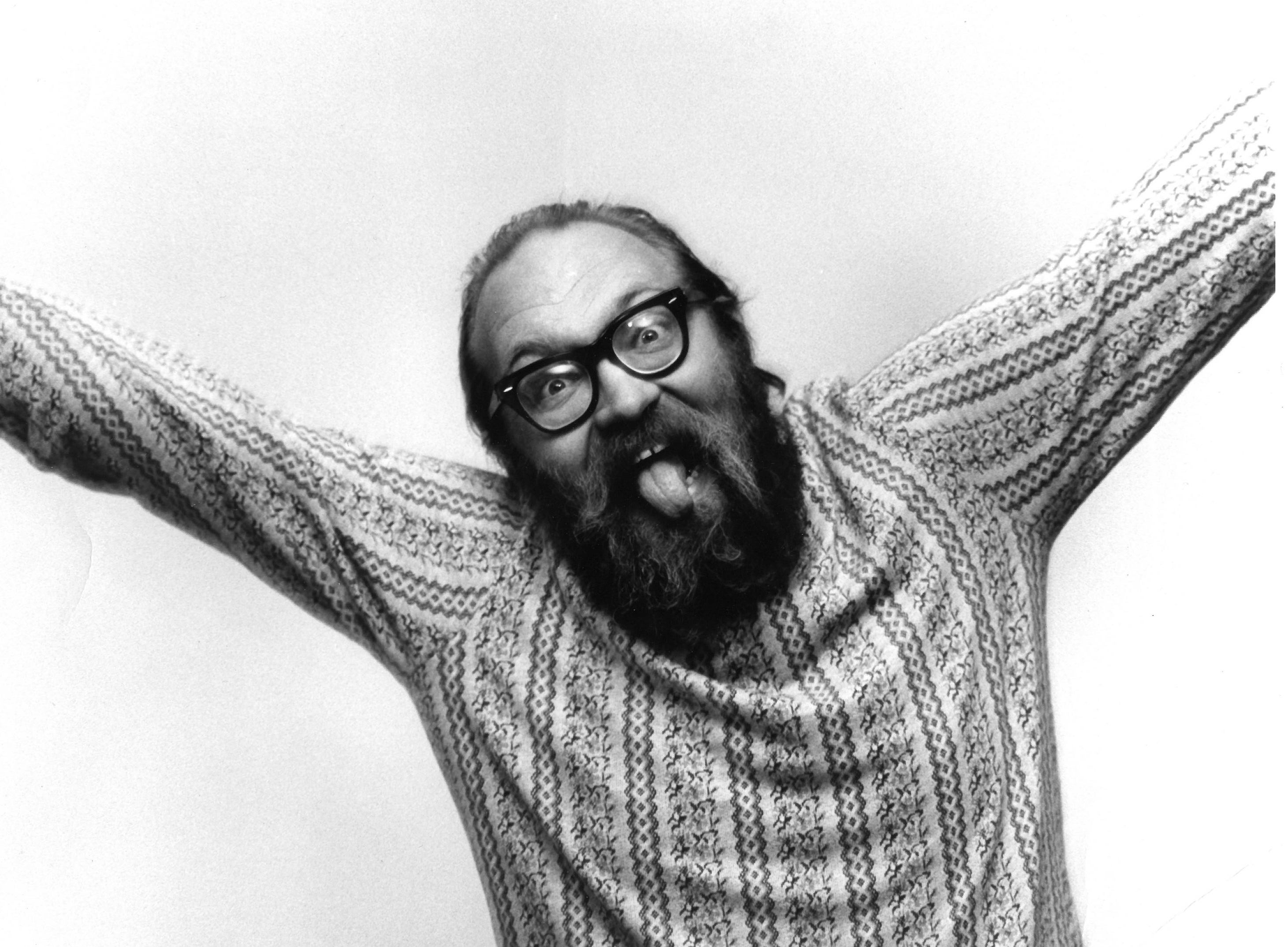

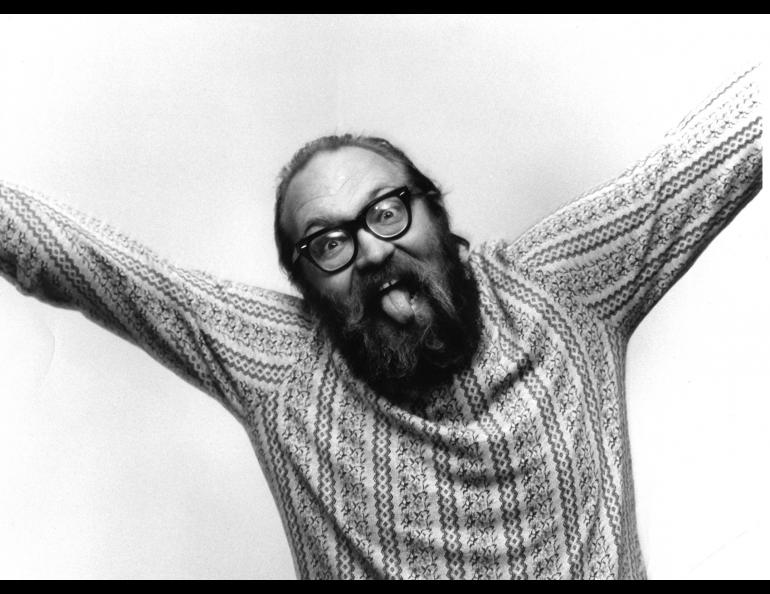

Begging his way aboard was Merritt Helfferich, then 34 and a do-all guy at the Geophysical Institute of the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Helfferich, whose life of adventures also included the first hot-air balloon flight from Barrow, Alaska, died in New Mexico on May 2, 2019. He was 83.

Back in the late 1960s, Helfferich heard of Humble Oil and Refining Company executives recruiting a team of Alaska engineers to ride the ship and measure the properties of sea ice it crushed along the way. He wanted in.

When the ship’s launch was delayed and invited professors needed to teach their fall classes, Helfferich shot up his hand. He was soon gasping in wonder at a dock in Halifax, Nova Scotia. There, he saw the giant ship he was to ride all the way north to Prudhoe Bay.

The largest ship ever to fly an American flag, the Manhattan busted its way north in search of heavy ice. If the Manhattan could prove its worth, Stan Haas and others with Humble Oil envisioned the recently discovered North Slope oil moving away from Prudhoe Bay in superships even larger than the Manhattan.

Helfferich remembered bunking on the ship in a section right over one of the nickel-iron propellers, so large the shaft that spun them was 18 inches in diameter.

“At a certain speed there was a maddening wah-wah-wah-wah,” he said in a 2013 interview. “We’d say, ‘Go faster or go slower.’”

When the sea ice bashed a Doppler speed-tracking system — one of the few setbacks for the ice-strengthened tanker — Helfferich and other scientists on board helped track the velocity of the Manhattan by throwing a block of wood to the ice and counting the seconds it took for the ship to pass it. His main duties were to helicopter out to ice in the Manhattan’s path and test its thickness, saltiness and other features he vowed to keep secret from oil companies that had not pitched in for the Manhattan experiment.

After leaving Chester, Pa., on Aug. 24, 1969 and reaching Prudhoe Bay and then Barrow by September 14, the Manhattan returned through the Northwest Passage and returned to New York by Nov. 12.

Helfferich, who was aboard for most of the trip before flying back from arctic Canada, remembered a smooth ride for the most part. The tanker-icebreaker handled most ice easily, though it sometimes needed to be nibbled out by icebreakers from Canada and the U.S. that accompanied it.

Despite a few problems, such as an iceberg puncturing part of the hull and being turned back by congested ice floes in McClure Strait (but still being able to reach Prudhoe Bay through Prince of Wales Strait), the Manhattan proved the possibility of moving oil year-round through the Northwest Passage. But Humble oil executives concluded an 800-mile pipeline was a cheaper way to go.

Helfferich flew back to Fairbanks after that 1969 adventure and got back to other endeavors, including a raft race 50 miles down the Tanana River and a rocket range in Chatanika that had his fingerprints all over.

Helfferich, smiling as he always seemed to be, once described his reaction to unusual proposals from bosses, co-workers and friends.

“I said yes to everything.”