The Man Who Made Portraits of Snowflakes

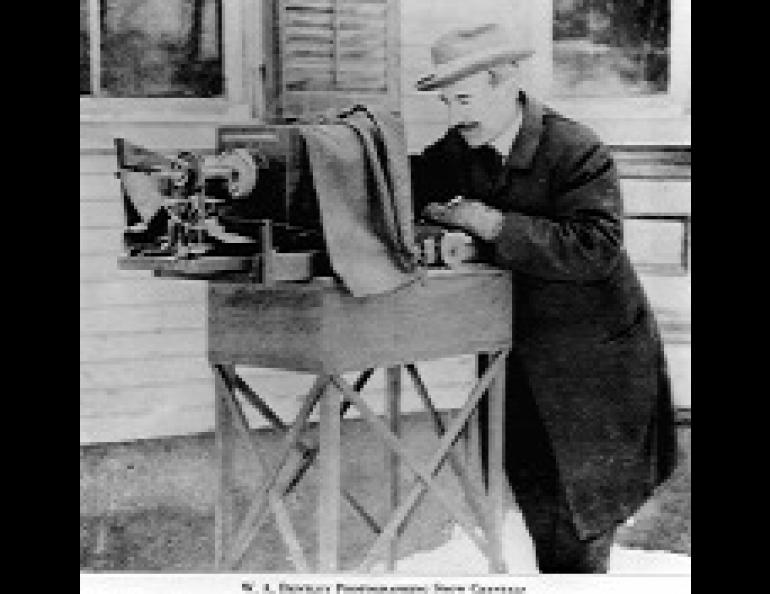

Jericho, Vermont, between 1880 and the 1930s. Snow. A man walks out of an unheated shed, holding a black board briefly into the swirling flakes, then goes back under cover and begins to examine the board with a hand lens, Sherlock Holmes in a blizzard. Carefully he lifts a bit of white from the board with a wooden splint, lays it gently on a glass slide, and brushes it lightly with a small feather to force it to adhere. Then under the microscope. Disappointment -- one of the delicate arms is broken. The board is brushed off and held into the snow again. Again the careful scrutiny, the gentle transfer, the feather brush, the microscope. This time his care is rewarded -- the snowflake is unbroken and symmetrical, a lacy gem of its kind. A different microscope is brought into play, this one on its side, pointing at the sky, with a camera bellows and a ground glass plate. Carefully the bellows and lenses are adjusted to produce a sharp image on the glass, while the man keeps the warmth of his breath and body well away from the microscope slide with its frozen captive. The lens is covered, and the glass plate is replaced with a covered photographic plate. The cover is removed from the plate, then from the microscope lens. It's a heavy storm, the exposure will need to be longer than usual. Forty seconds pass before the lens is covered again, then the plate, which is removed and added to the growing stack in the shed. The man glances at the sky, consults his watch. Time to get another photo or two before the light fails. Again the board is held out into the falling snow.

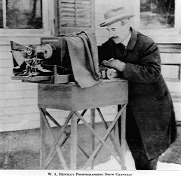

No record survives of what W. A. Bentley's Vermont neighbors thought of his hobby. But as the years passed and he shared his microphotographs with artists and scientists around the world, his work became recognized as a unique contribution to the study of ice crystals. He was not the first to study snowflakes; Johannes Kepler, who had deduced the orbits of the planets, wrote a charming little book speculating on why snowflakes were hexagonal, and finally concluded that the answer was beyond his powers. By early in the nineteenth century, Arctic explorers such as Scoresby were making careful drawings of snow crystals. But Bentley's work was unique in the objectivity of the camera lens. His admirers were concerned that his photos not be lost, and finally an anonymous donor presented the American Meteorological Society with the funds to publish the best of Bentley's snowflake photos, together with a few of his other, related photos -- of windowpane frost, raindrops, and dew.

Bentley was not fully satisfied with his photographs, however. There are two ways to make a microphotograph: with light from above or to the side of the subject, which shows surface texture only but gives a dark background, and transmitted light, which shows internal structure but gives a light background. Bentley's photos used transmitted light, as much of the pattern in a snowflake is due to air inclusions which can only be seen in this way. In order to increase the beauty of the photos chosen for the book -- almost twenty five hundred of them -- Bentley made duplicate negatives and carefully cut away the background from each snowflake. The result was images with all the detail possible only with transmitted light, but looking as if photographed against black velvet.

There are more recent collections of snowflake microphotographs than Bentley's. Some of these, with far more detailed information on the temperature and moisture conditions under which the flakes grew, have superseded his in scientific usefulness. But "Snow Crystals" by W. A. Bentley and W. J. Humphreys, originally published in 1931 and republished by Dover in 1962, is still the most beautiful collection of snowflake photographs available.