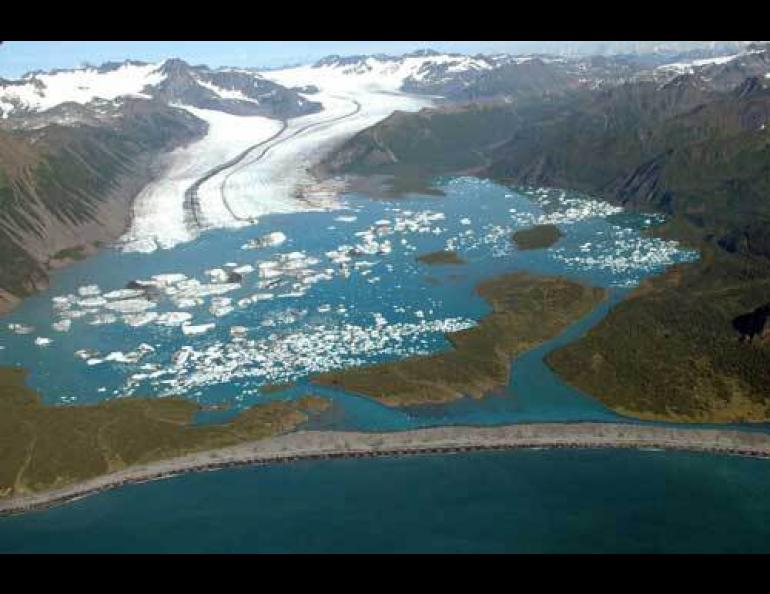

Bear Glacier on the Kenai Peninsula floating on a lake of its own creation, photographed in 2005. Photo by Bruce Molnia, USGS.

Ptarmigan hammer the willows on Alaska’s North Slope during their spring migration from mountains to the lowlands. Photo by Ken Tape.

More tales of a changing Alaska

More Alaska-related news from the notebook after a week at the December meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco:

- In autumn 2007, temperatures north of Alaska over the Arctic Ocean were about 10 degrees Celsius warmer than longtime averages, and in November there was still open water on the Chukchi Sea. “These are most likely the largest temperature anomalies on the globe for autumn,” said John Walsh of the International Arctic Research Center during a talk he gave at the conference. Walsh said that open water on the ocean and the heat it absorbs make the Arctic a real driver of the entire world’s increased warmth during autumn and early winter, and that role will only be enhanced if sea ice on top of the globe continues to decline. He also said the open water at the end of summer may have made the region stormier. Because the ice-free zone north of Alaska and Siberia persisted well into autumn, the ocean was able to provide the atmosphere with an extra supply of heat and moisture, the perfect ingredients for storms. Walsh said increased turbulent weather caused by open water is what climate models predict and what people observed in the Bering Sea region last fall.

- Many Alaska glaciers seem to be behaving like ice at the planet’s opposite extreme in Antarctica. Glacial geologist Bruce Molnia of the U.S. Geological Survey and an adjunct professor at the University of Alaska has watched Bear Glacier on the Kenai Peninsula and about 50 other Alaska glaciers follow a pattern. Molnia has noted that many glaciers thin so much they float on the surface of a deep-water lake of their own making, and then meltwater beneath the heavily crevassed glaciers inspire a dramatic breakup that features tabular icebergs. “The Antarctic ice shelves always have floated and had lots of crevasses, but they just recently got warm enough to have abundant meltwater fill the cracks and crevasses,” Molnia said. “This resulted in the catastrophic failure of the Larsen B Ice Shelf.” In Alaska, glaciers have always had the meltwater and crevassing elements, but recent warming has resulted in the rapid thinning of many glaciers, resulting in their tongues beginning to float, Molnia said.

- Birch shrubs seem to be responding best to a warmer North Slope, according to studies done by a few researchers. Robert Pattison of University of Alaska Anchorage and his colleagues have found during a 12-year study that shrubs are increasing on the North Slope and “dwarf birch is doing particularly well.” The University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Eugenie Euskirchen used a model to indicate that the net primary productivity of birch species in shrub tundra was three times larger than any other plant.

- One overlooked agent of change in Alaska’s far north might be the ptarmigan, according to Ken Tape of UAF’s Institute of Arctic Biology. On spring traverses he’s done recently by dog team, Tape noticed that ptarmigan have eaten willow buds from stems that stick above the snowline. In certain areas, “Ninety-seven percent of the buds were gone (just above the snow),” he said. “It’s like hedging or something. Then they perch on branches to eat higher buds.” He said “tens of thousands” of ptarmigan hit the willows on their migrations from the Brooks Range to the North Slope, in January and February and then in April. The willows, which like birch shrubs seem to be thriving under changing conditions on the North Slope, are in turn benefiting ptarmigan and moose, Tape said.