Northern lab cranked out the quirky and controversial

“Rectal Temperature of the Working Sled Dog.”

“Cleaning and Sterilization of Bunny Boots.”

“Comparative Sweat Rates of Eskimos and Caucasians Under Controlled Conditions.”

These are some of the studies completed by scientists who worked for the Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory from the late 1940s to the 1960s. Developed during the Cold War to “solve the severe environmental problems of men living and working in the Arctic,” the lab cranked out dozens of quirky and sometimes controversial publications.

Based at Ladd Air Force Base in Fairbanks, which later became Fort Wainwright, the Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory was a group of about 60 military and civilian researchers charged with finding the best way to wage warfare in the cold. At the time, U.S. political and military leaders feared a nuclear or conventional war with the Soviet Union and thought that Alaska was a likely battleground.

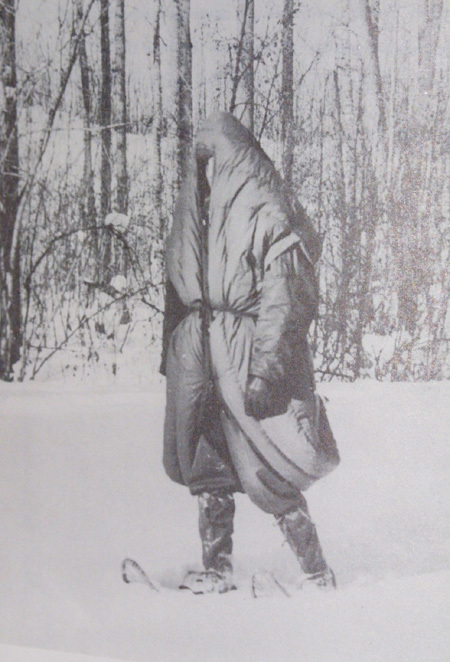

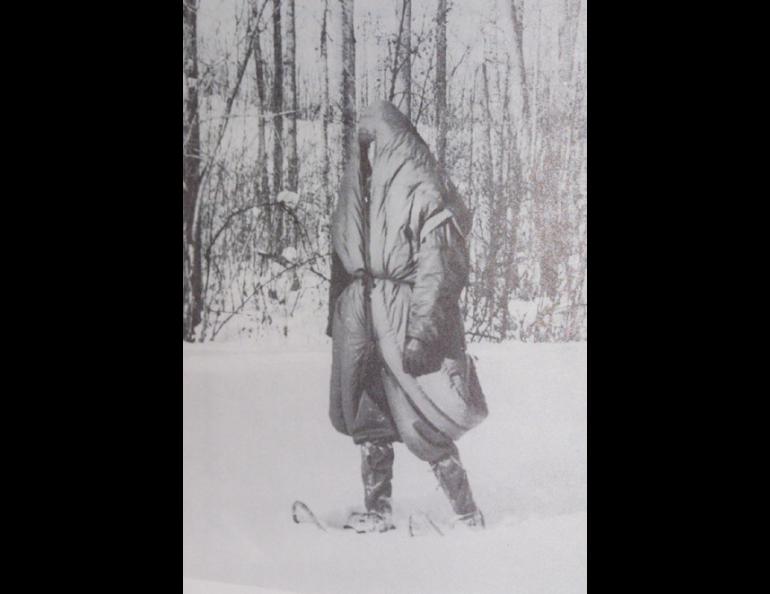

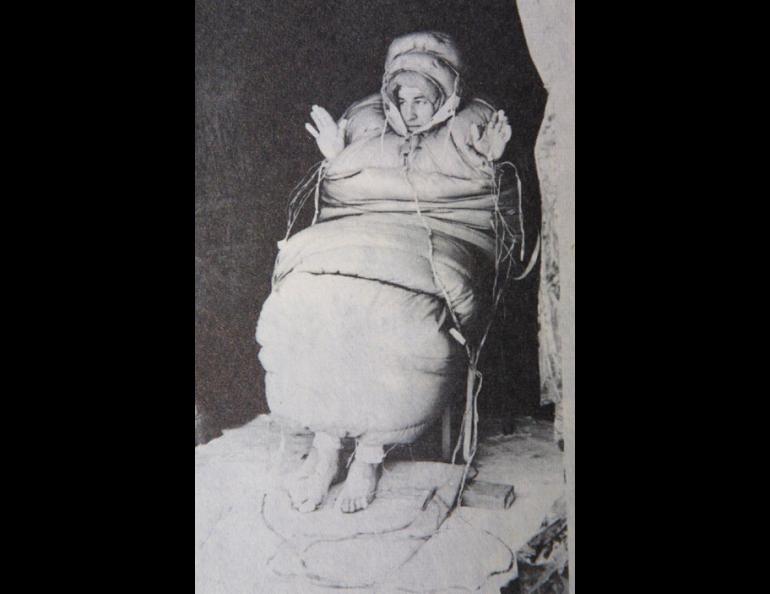

Projects from the Air Force lab in Fairbanks included cold-weather gear development (as in Technical Report 59-4, “Walk-Around Sleeping Bag,”); studies of the body structure and function of bears, ground squirrels, and other animals that hibernate; and comparisons of different races of people to determine if Eskimos, for example, were better adapted to the cold than non-Native soldiers.

Many people later criticized one of those studies, on the role of the thyroid gland in acclimation to the cold, because researchers in 1956 and 1957 gave capsules of iodine 131, a radioactive material used to trace thyroid activity, to102 Alaska Natives from five northern villages and 19 military volunteers. The National Research Council in the 1990s investigated and found ethical problems with the study but decided that the damage done by the capsules was probably “negligible,” and that the scientists “held a genuine belief, justified at the time, that their research was both harmless and important.”

Less publicized was the lab’s “simulated survival trek” from Anaktuvuk Pass to the Arctic Ocean by an Air Force captain and staff sergeant in July 1962. The men were given an aircraft survival kit and instructed to hike and float their way to the Beaufort Sea. Their objective was to “provide field experience in this area and to determine the merits and deficiencies of the F-102 Aircraft Survival Kit.”

The first deficiency the men found was the lack of raingear, which forced them to drape their small life rafts over their heads to stay dry “with only partial success . . . Both ‘survivors’ were shivering uncontrollably and had to call on considerable will power to make camp,” they wrote. Upon completion of their trip, with the help of an “observer” who traveled next to them in the Colville on a larger raft, the men recommended that a future version of the survival kit include both lightweight rain gear and salt, which they craved after shooting ground squirrels and netting whitefish.

Shivering volunteers must have been a common sight at the Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory, where researchers quantified how different areas of the body generate and lose heat. In one experiment, scientists found that no matter how thick the insulation covering the body core, a person’s hands and feet will always get cold if uncovered. To combat these weak points, the lab developed heated bunny boots and heated gloves powered by a seven-pound battery vest that would allow a person to remain somewhat comfortable standing around at 40 below Fahrenheit.

The mental health of the northern soldier was also a favorite topic of study. In one of the lab’s reports published in 1950, an Air Force major wrote about differences between infantrymen who came to Alaska from either the southern or northern U.S.

“It was found that the men from the South are significantly more depressed than those from the North, although the latter group expresses disposition changes indicative of increased frustration,” he wrote. “Both groups are similar in experiencing increased tension, lack of sociability, insomnia, and feeling of increased aggression."