Northern woods filled with potential drug

Saplings of the Alaska paper birch tree produce a sticky resin on new branches that discourages snowshoe hares from eating them. Some scientists think that such chemical defenses might be useful drugs and a new natural resource for Alaskans to tap.

Tom Clausen and John Bryant think so highly of birch trees’ promise that they took a 600-mile journey up and down the Porcupine River early this summer to clip birch twigs from different locations. Using Clausen’s 21-foot wooden strip boat with a 30-horsepower motor, the researchers compared twigs from Circle all the way up to Old Crow in the Yukon Territory. They found new twigs of birch were more heavily encrusted with resin nodules the farther north they went.

“As we went upriver, the trees got gooier and gooier,” said Clausen, the chairman of the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

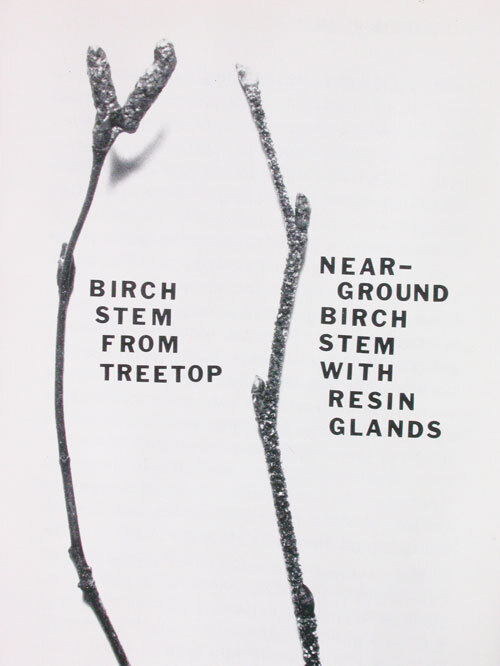

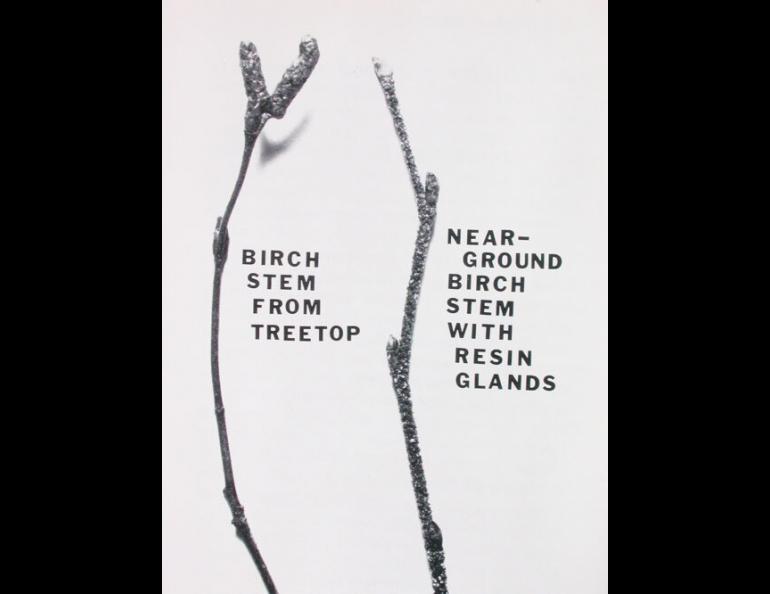

In the late 1970s, Bryant, a UAF professor emeritus who now lives in Wyoming, noticed that Alaska birches seemed to protect themselves from hares by producing resinous glands on saplings and stems growing close to the ground. Current UAF Provost and chemist Paul Reichardt determined that the stems of birch saplings are stubbled with tiny beads of papyriferic acid, a sweet compound with a bitter aftertaste. Twigs growing higher on mature trees don’t have the glands.

“When a tree gets knocked down, the tops are like candy for hares,” Clausen said.

The papyriferic acid on sapling twigs causes snowshoe hares to pass more sodium with their urine. This loss of sodium indicates birch defenses, such as papyriferic acid, which are potential hypertension drugs, Bryant said.

“Papyriferic acid and other substances are clearly affecting hares, and things that affect mammals are of interest as potential drugs,” Clausen said. Medical researchers first derived aspirin, for example, from a chemical extracted from willows, and the cancer drug Taxol originated in Pacific yew trees.

The north has a bumper crop of birch and other trees and shrubs that seem to be loaded with papyriferic acid and other potentially valuable chemicals. Bryant has sampled trees from Connecticut to Galena, and the northern ones are the richest.

“In Connecticut, trees contain no papyriferic acid; Old Crow trees have 50 percent,” Bryant said. “That’s a huge difference.”

On their recent trip to the village of Old Crow and beyond, Clausen and Bryant found a striking relationship between forest fires, snowshoe hares, and resinous birch. The extreme forest fires of the North—an area the size of Vermont burned in Alaska in 2004—could be a reason why it’s such a storehouse for papyriferic acid and other natural chemicals.

“Fire yields hare habitat, which yields hares, which yields hares eating plants, which yields juvenile plants evolving a chemical defense against hares,” Bryant said.

Since the birches with the highest concentrations of the chemical are between Fort Yukon and northwest Canada, Bryant envisions potential for villagers to start a new industry of harvesting young birch and other woody plants. This sort of small industry is already underway in Minnesota, where researchers from the University of Duluth have joined a biotech company to harvest birch bark for betulin, a chemical effective as a herpes and skin cancer drug, and as a component of cosmetics.

“If one wants to look for drugs, it makes sense to look at plant-mammal interactions,” said Bryant, “and the strongest plant mammal interaction is between hares and trees and shrubs of northern Alaska and northern Canada.”

“There’s tons of this stuff right outside our door,” Clausen said.