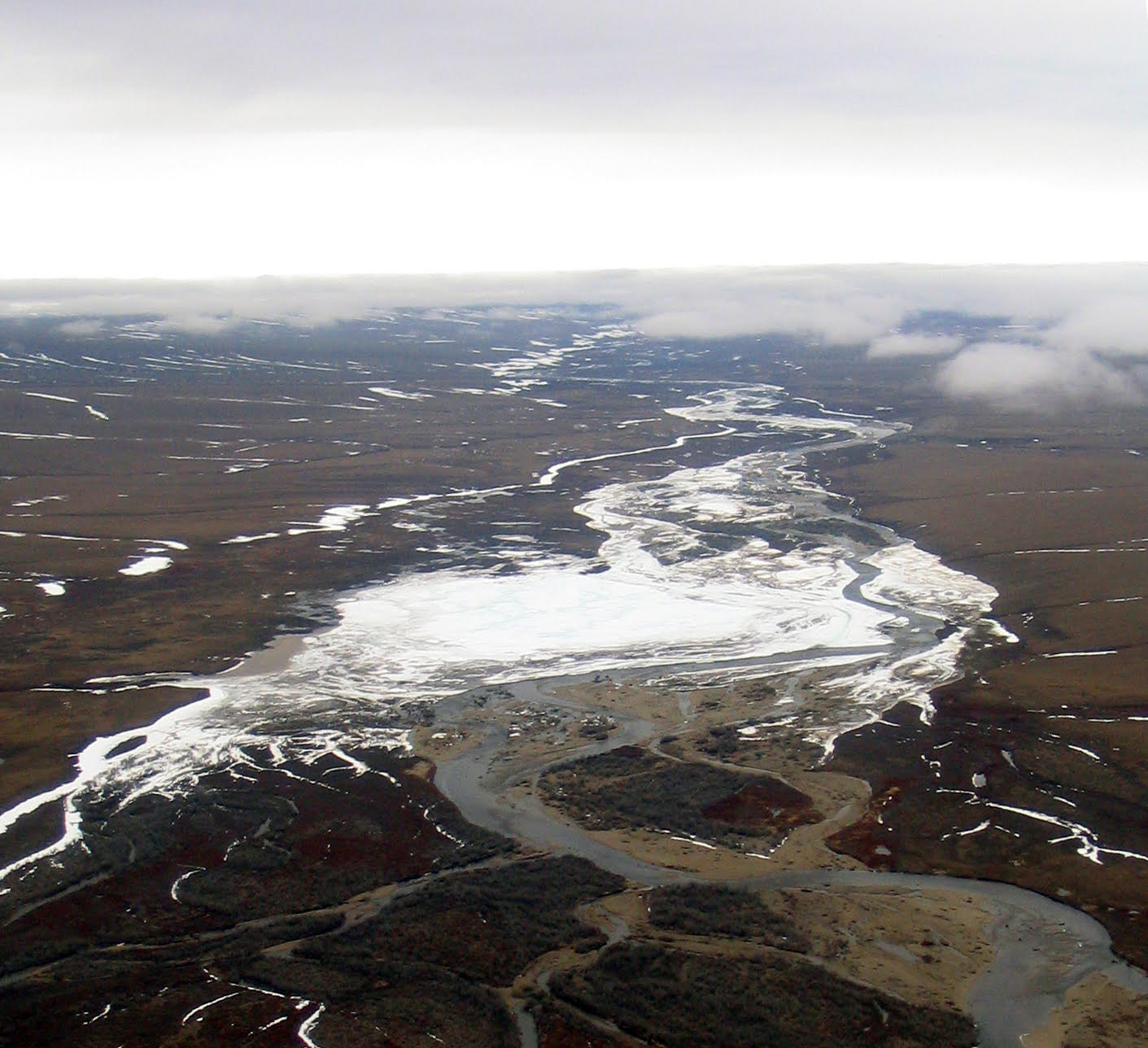

Overflow ice as northern oasis

Overflow ice, also known as aufeis, is like a field of arctic daisies that comes back year after year. Aufeis that clogs northern valleys is born when frigid winter air meets cold water welling up to the ground’s surface. Aufeis dies when warm air finally melts it in July or August.

Fields of aufeis (“off-ice”), some covering entire valley bottoms 10 feet thick, can terrify people who float northern rivers. While swatting at moose flies on 80-degree June days, rafters might see their river disappear into an ice cave ahead.

Because these white features that endure long into the green of summer are so striking, scientists have studied them for years. They have found that aufeis (German for “ice on top”) is often downstream of underground springs that gush all winter long.

Many Alaskans know this ice as overflow. Its gradual buildup has created glaciers on Alaska roadways and has in midwinter forced people from cabins as their property slowly transformed into a skating rink.

Though many scientists who have looked at aufeis have been engineers or hydrologists, a team of ecologists are likening the ice fields to oases in the cold desert of the Arctic. Aufeis, they think, enhances the diversity of northern life both in summer and winter.

Living in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Alex Huryn sleeps a long way from the nearest aufeis, but he has traveled to UAF’s Toolik Field Station for decades and is co-author on a book of the far north’s natural history.

Huryn is lead scientist on a study of a resilient spread of ice on the Kuparuk River. The Kuparuk flows from near Toolik Field Station north of the Brooks Range across 200 miles of flats to the Beaufort Sea.

Not far from Toolik Lake, a giant pan of aufeis forms each winter and endures most of the summer, crowding the gravel floodplain of the Kuparuk River. Huryn and his colleagues have probed and sampled and aimed radars at the ice and the underlying riverbed.

They are finding that the ice seems to be enabling year-round life in that frigid, dark place. As it melts in summer, the ice rejuvenates the river by providing nutrients and edibles to downstream creatures. Aufeis fields can provide one third of a river’s summer flow.

By sampling water from PVC pipes drilled into the ground beneath the ice, the scientists found evidence of of flatworms, stoneflies and other small creatures eaten by grayling and other fish.

In winter, the ice insulates the riverbed from 40 below zero air, creating a sanctuary at a time unfriendly for most life forms.

“We’re finding (30 feet) of unfrozen habitat during winter,” Huryn said. His study on the Kuparuk aufeis field continues until 2019.

Huryn’s findings come at a time when another researcher, Tamlin Pavelsky at the University of North Carolina, documented the wane of aufeis fields on Alaska’s North Slope and nearby arctic Canada.

Following up on an observation by Alaska pilot Kirk Sweetsir, who noticed aufeis fields shrinking and sometimes disappearing, Pavelsky looked at satellite imagery and compared ice conditions in 2000 to the present. He found that 70 of 122 ephemeral aufeis fields in northern Alaska and Canada are disappearing “significantly earlier in the summer.”