Pollen scientist was one of a kind

Jim Anderson has died, and the world is a more boring place.

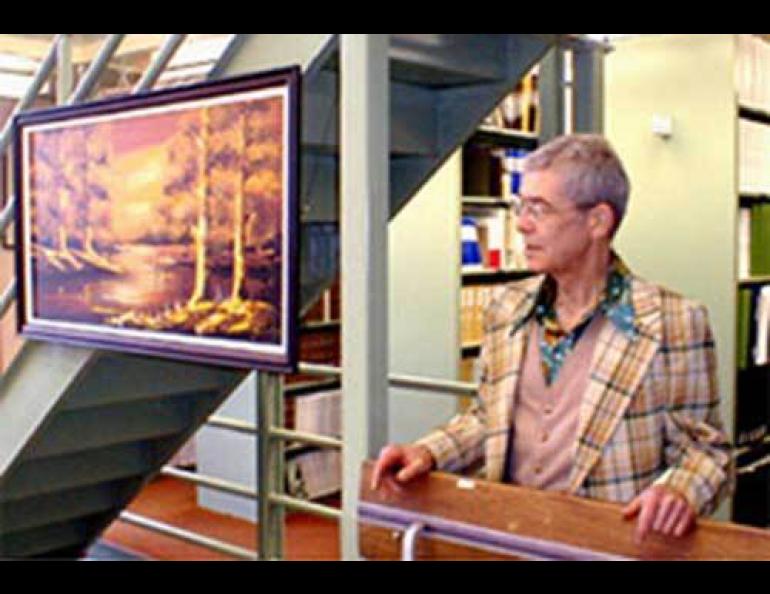

Anderson was 66. He suffered from ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease, for several years before his death. A few weeks ago, the disease killed him. I felt a pang of loss even though I spoke only a few times with the former librarian of the Biosciences Library at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

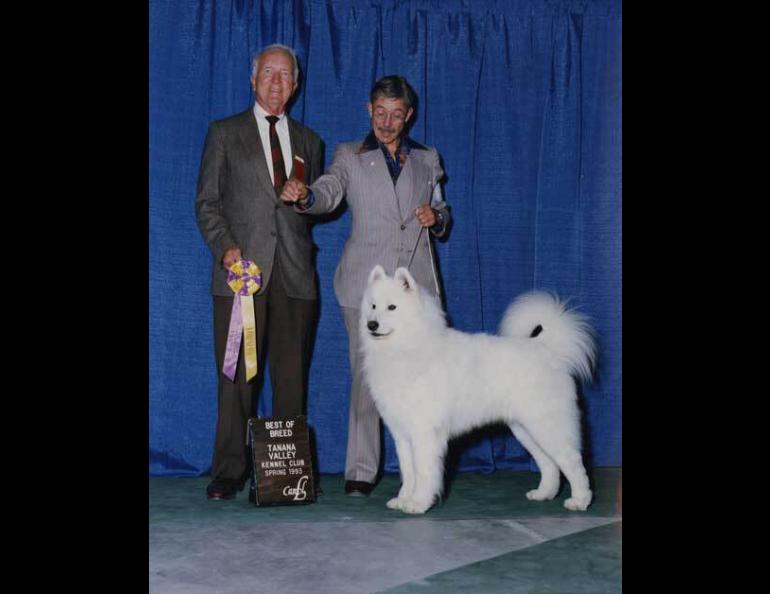

I remember a man who dressed in colorful plaid jackets with wide lapels, someone who was a good interview because he knew his stuff so thoroughly. Until his death, I didn’t know he lived alone in a cabin with two Samoyed dogs, 25 typewriters, hundreds of teddy bears, 700 sport coats, and that he had a collection of 12,000 books on his property.

“Sometimes I think people noticed only the eccentricities and the compulsions Jim had (such as collecting 7,000 neckties), and miss the value of that very compulsiveness,” Karen Jensen wrote in an email. Jensen was Anderson’s co-worker for a few years at the Biosciences Library.

One of those compulsions for Anderson was the study of a small airborne irritant that each spring makes life miserable for one in five northern people: pollen. For years, he sampled pollen with a mechanized air-sniffer on the roof of the Arctic Health building on the UAF campus. By being meticulous in counting the pollen grains trapped on the clear film of his samplers, Anderson came up with a pollen calendar for Fairbanks, and later Anchorage. His calendar shows that birch trees in both cities release the most pollen—up to 4,500 grains per square meter of air—from May 10 through the 20th.

Birch pollen grains are so small that eight of them could fit on a period. People’s immune systems react to the protein coating, called exine. “EXINE” was also the word on the license plate of Anderson’s van.

He climbed to the roof for his pollen counts every day in spring, and spent many hours looking through a microscope to see what species of pollen were stuck to his slides. He found that the concentration of pollen in the air was highest three days after birch leaves popped from buds.

“He loved that phenomenon, how predictable it was,” said Dr. Tim Foote, a pediatrician and allergist at the Tanana Valley Clinic in Fairbanks. “Before Jim, nobody even had a name for what the pollen was (that irritated them). Everybody thought it was spruce pollen that was bugging them.”

Anderson helped Foote, and his colleague Susan Harry, set up pollen counters at the clinic. Now, thanks to Anderson, they can alert patients to the worst pollen days.

“He championed a cause that very few clinicians or patients knew anything about,” Foote said. “I loved him—he was the epitome of a scientific mind.”

Beginning in 1974, Anderson also kept a 30-year record of the date of “greenup” in Fairbanks, when leaves emerged on a hill visible from the university.

“He was looking at the idea of whether he could look at global warming with the greenup data,” said Carol Haas, who worked with him at the Biosciences Library.

Anderson grew up in Kennewick, Washington, and went to college at the University of Washington, Michigan State, and Brigham Young University before settling in Alaska in 1970. He found himself attracted to the solitude of the Goldstream Valley north of Fairbanks in 1974. He lived there most of his adult life.

“It’s heaven out there,” he once told journalist Tom Delaune.

Anderson, who left his books, typewriters, and other possessions to UAF, was different, Karen Jensen said, but that was his gift.

“The fact that he was a rather odd man is to me proof positive that this world really does need all kinds of people, and that while most of us fall comfortably into conformity, those who don’t—like Jim—might have something really terrific to contribute.”