The rusting of northern Alaska streams

During these late winter days, researchers who are studying the rusty discoloration of northern Alaska streams are prepping for summer field trips.

Jon O’Donnell of the National Park Service is one of a team of scientists who will float rivers and streams in Kobuk Valley National Park and Noatak National Preserve in 2024.

He and his co-workers will be armed with equipment designed to help understand what is making northern rivers turn orange, and how dangerous it might be to people, plants and fish.

In the past decade, scientists such as Roman Dial of Alaska Pacific University and Paddy Sullivan of the University of Alaska Anchorage noticed on their long traverses that waterways they had remembered to be as clear as gin were suddenly flowing orange.

Some investigation and deep thought has led to this hypothesis: Though rivers and streams of the far North have probably turned rusty naturally to some extent for a long time, “things got more intense after 2018,” said Josh Koch of the U.S. Geological Survey Alaska Science Center in Anchorage.

“It’s not totally unprecedented, but the scale and intensity seem to be something new,” Koch said during a December 2023 presentation at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco.

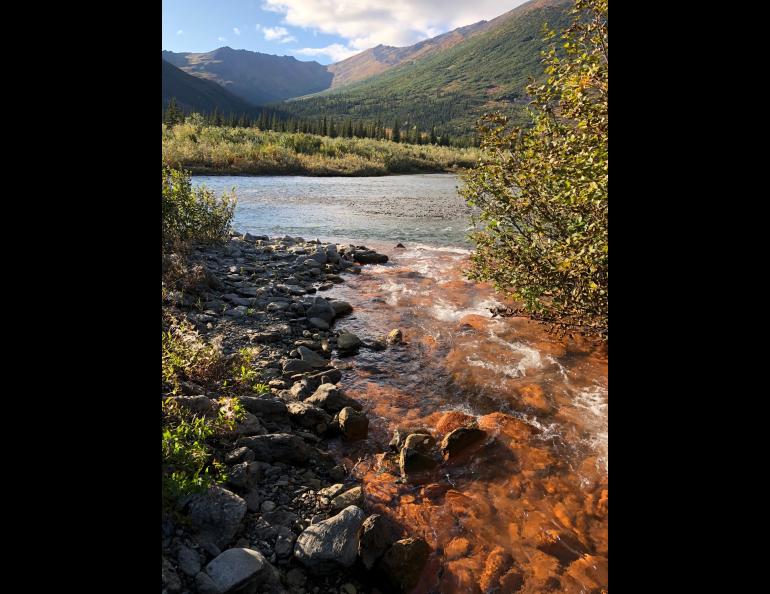

The oranging of northern rivers seems to be related to recent permafrost thaw that has allowed streams to release previously captive iron, trace metals and acid.

“Under colder climates in the past, these minerals were protected from weathering and interactions with groundwater,” O’Donnell said.

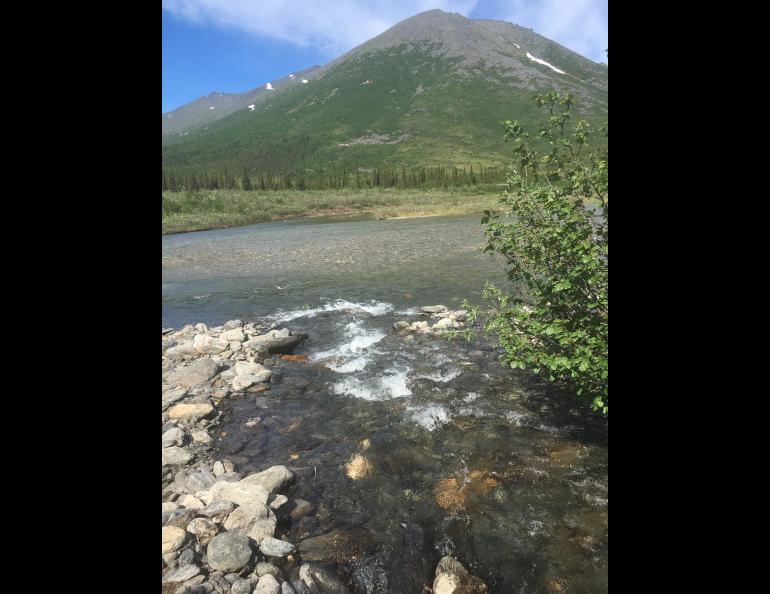

O’Donnell, Koch and others with the two agencies had the good fortune of in 2017 setting up a station to monitor stream chemistry and the living creatures present there in a clear tributary of the Akillik River in Kobuk Valley National Park.

When they returned in August 2018, they noticed their clear little creek had turned orange like so many others they had been noticing.

“This seemed like a strange disturbance that we should try and understand. But in general, it seemed anomalous,” O’Donnell said. “I hadn't seen anything like it in the Brooks Range. I figured our data could tell a cool story, or at least provide an interesting anecdote. But I was completely unaware of the scale.”

During that visit by helicopter in 2018, O’Donnell, Koch and USGS biologist Mike Carey noticed “a complete loss of resident fish — like Dolly Varden and slimy sculpin,” Koch said.

The creek had also become more acidic, fed by groundwater seeps with a pH reading of about 2, stronger than most off-the-shelf vinegar. The scientists think the fish may have moved somewhere else as their creek was becoming unlivable.

“We observed a steep decline in stoneflies, mayflies and other aquatic larvae (which are food for fish),” O’Donnell said. “It’s likely that the fish migrated out.”

Researchers have noticed more than 70 orange streams spanning the Brooks Range from the lower Noatak River to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in the east. Because the phenomenon can often be seen in a satellite view of an area, O’Donnell and his colleagues found many of those streams changed color in the last 10 years.

Streams have the ability to clear themselves. Sometimes, heavy summer rains can overwhelm the particles of iron and other trace metals, clearing the water while rocks remained stained. Permafrost within and surrounding a stream can also “recover” due to extreme cold conditions or lack of snowfall. That could lock up the reactive minerals.

On their northern explorations in summer 2024, Koch, O’Donnell and other scientists will try to determine how bad the orange streams are for fish and the tiny things they eat. High levels of trace metals like copper, nickel and zinc are not good for living things.

“It seems likely there’s a toxic effect, but we don’t know yet,” Koch said.