A search for the coldest ice worm

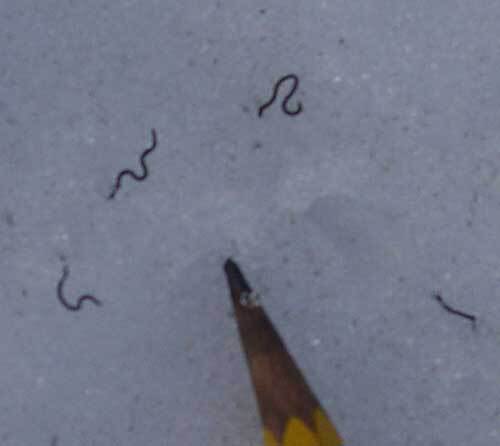

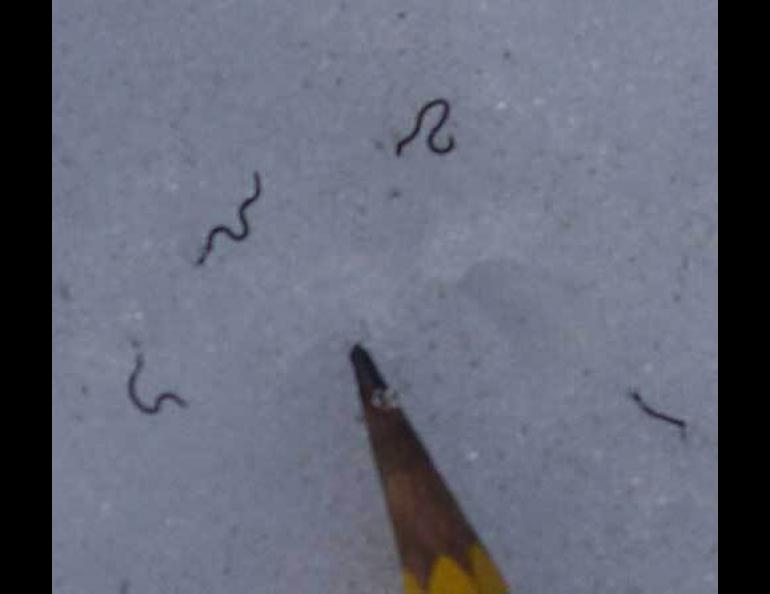

Ice worms, so small and wispy that several would fit on your fingertip, live on warmish glaciers, eating algae and slithering toward the few spots in the narrow range of temperature they can endure. Ice worms die if the temperature drops much below freezing. At temperatures comfortable for humans, they disintegrate.

This summer, a few biologists are making a ski-and-crampon trek over the glaciers on the south side of the Alaska Range to see if rumors are true of the ice worm’s existence there. Ice worms typically live on warmer glaciers in lower latitudes or near the coast of Alaska, not on the colder ice of the Interior.

“A worm in Denali would have to be a bit different to survive the harsh winters,” said Rutgers professor Dan Shain, a trekker and one of the few people who study ice worms.

Shain, Alaska Pacific University professor Roman Dial, and a few others are making a ski and packraft traverse of the southern Alaska Range this August in search of the ice worm. Mountaineers, pilots, and park rangers have reported seeing ice worms on glaciers within Denali National Park.

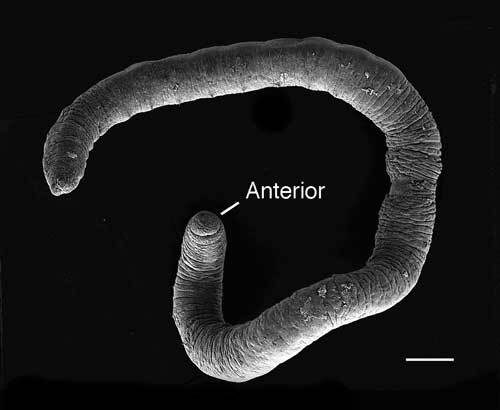

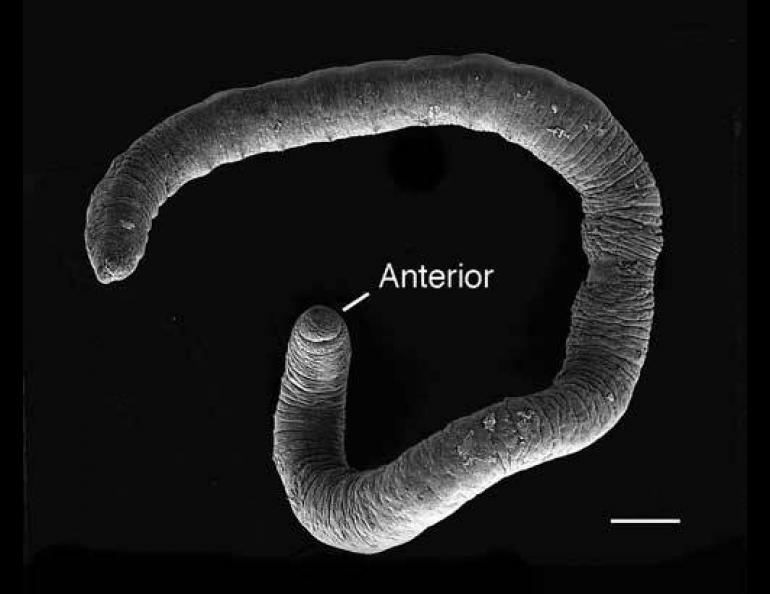

For the past six years, Shain has stepped foot on more than 100 glaciers from Oregon to Alaska, finding ice worms on level snowfields, steep cones of avalanched snow, crevasse walls, hard glacier ice, and glacial rivers and pools. The worms are similar in structure to earthworms, but an inch-long ice worm is a large one. They are as thin as thread, and are super sensitive to temperatures. Ice worms freeze and die if their bodies drop just a few degrees below 32 Fahrenheit, and dissolve at temperatures warmer than about 40 degrees.

How does such a fragile creature survive? Ice worms stay within glacier ice during the heat of the day, but squirm to the surface in the evening. For this reason, the group will be on the lookout for worms after 8 p.m. on the Denali National Park trip. Nobody knows where ice worms spend the winter, but Shain said they probably burrow within ice and snow that provides insulation and temperature stability during the darkest of days.

And what does this unlikely creature eat? Shain said the worms appear to feed on the single-celled algae that grows on glaciers, and may also eat bacteria, fungi, and other organic material the wind blows onto glaciers.

During the current trip, the biologists will use their mountaineering skills on a traverse over glaciers flowing south from the high peaks of the Alaska Range. They plan to fly from Talkeetna onto the Eldridge Glacier, then ski and walk over glaciers just south of Mt. McKinley, including the Buckskin, Ruth, Tokositna and Kahiltna glaciers. Shain spoke with a climber who saw Alaska Range ice worms that were small enough to fit on his fingernail with room to spare. That body size—probably smaller than ice worms on glaciers farther south—might be an adaptation to living on colder northern glaciers.

If the group finds ice worms, Shain will collect several hundred and bring them back to his lab in New Jersey to see how different the worms are from those living much farther south.

“Finding them would be great, and would likely mean a new species to science,” Shain said. “The alternative (not finding them) is less appealing, but that is the risk.”