The Splitting of the North's Largest Ice Shelf

Off the northern coast of Canada, a chunk of ice larger than Chicago has fractured for the first time in several thousand years.

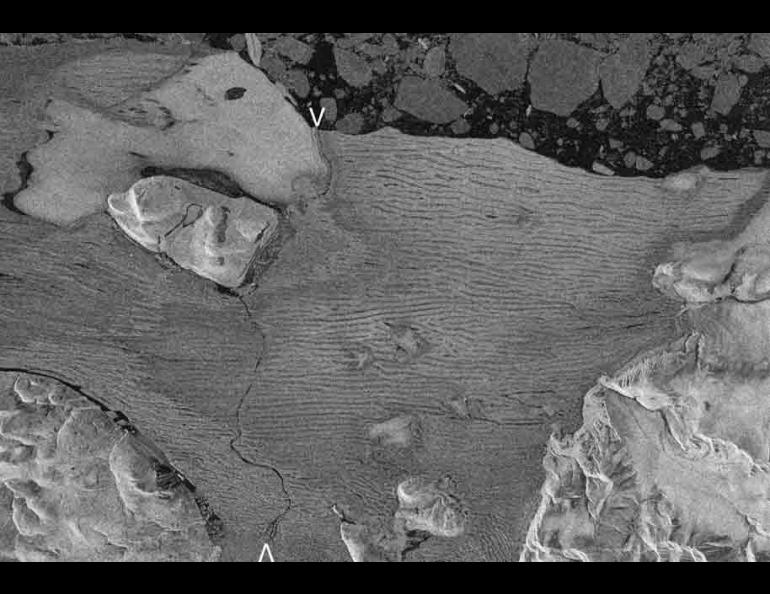

The Ward Hunt ice shelf, the largest of its kind in the Arctic, broke in two and developed many other cracks within the last three years. Scientists including Martin Jeffries of the University of Alaska’s Geophysical Institute made this discovery during visits to the mass of ice and by reviewing satellite images received at the Geophysical Institute’s Alaska Satellite Facility.

The crackup of the ice shelf has attracted comparisons to the drastic calving of ice shelves in Antarctica, which many scientists believe is compelling evidence of global warming.

Martin Jeffries knows the Arctic’s largest ice shelf better than most people; he has camped for weeks on the 270-square-mile mass of ice, which is frozen onto the northern shore of Ellesmere Island. In the 1980s, Jeffries earned his doctorate degree while studying the formation of the ice shelf, a source of icebergs that could endanger oil platforms in the Arctic Ocean. Part of Ward Hunt’s recent breakup showed why oil companies are concerned; in August 2002, the northern edge of the ice shelf broke off into the ocean, releasing about 10 ice islands with a combined area of more than two square miles.

“This is the first time we have actually witnessed—through people on the ice and by satellite—the appearance of fractures in the ice and the catastrophic drainage of an epishelf lake,” Jeffries said.

Until the recent fracture, the ice shelf served as a barrier that held a freshwater “epishelf lake” on top of salt water in 20-mile long Disraeli Fiord. Jeffries’ colleague Derek Mueller of Laval University in Quebec measured the layer of freshwater that sat on top of seawater in the fiord in 1999 and found it to be about 90 feet deep. He found the freshwater later decreased to about nine feet when he measured again in July 2002. He later flew over the ice shelf in a helicopter and noticed a crack running the length of the ice sheet from the fiord to the open ocean. When most of the freshwater disappeared, so did many unique species of organisms that lived in the fresh and brackish water. Scientists looked to the life forms in Disraeli Fiord’s epishelf lake as possible analogues to life on colder planets.

Disraeli Fiord now has a direct connection to the ocean for the first time in thousands of years. Before the fracture appeared, researchers found ancient driftwood from the Mackenzie River and Eurasia in the lake; no wood samples were younger than 3,000 years, hinting that the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf has sealed the fiord off from the Arctic Ocean for at least that long.

During the explorations of Robert Peary in 1907, The Ward Hunt Ice Shelf was a small part of a giant ice shelf on the northern rim of Ellesmere Island. By 1982, the ice that Peary saw had lost 90 percent of itself to the Arctic Ocean. In the last 20 years, the remaining ice, the Ward Hunt ice shelf, remained stable.

Now, the ice shelf is broken into two major parts and many smaller ones, and warmer temperatures may be to blame. At Alert, a small outpost nearby on Ellesmere Island, observers recorded a temperature increase of about one-half of a degree Celsius each decade since 1967. Though the splitting of the Ward Hunt ice shelf may be due in part to other factors, its behavior at a time of so much warming in the Arctic seems more than a coincidence.

“It’s the largest change in 40 years and it comes at a time when there are many other parts of the cryosphere in the Arctic also changing,” Jeffries said. “This could be additional evidence for Arctic environmental change.”