Tiny, ancient life discovered in Southeast

In a world crawling with insects, those billions of tiny bodies fall into just 30 major descriptive groups, known as orders. That’s why Derek Sikes, curator of insects at the University of Alaska Museum of the North, was disappointed with a graduate student when she failed to identify a creature that was wandering her plots on Prince of Wales Island.

“Every entomologist should be able to ID every insect to its order just by looking at it,” Sikes said.

Jill Stockbridge, doing research for her master’s degree work on spiders and beetles on Prince of Wales Island, tried her best to identify “little tiny spots jumping around like fleas.” When she could hesitate no more, she called Sikes for help.

“I thought I knew what it was,” Sikes said. “It had features of a wingless wasp or a bark louse, but it wouldn’t key out.”

“I felt way better when he didn’t know either,” Stockbridge said recently in the Entomology Lab in the UA Museum of the North in Fairbanks.

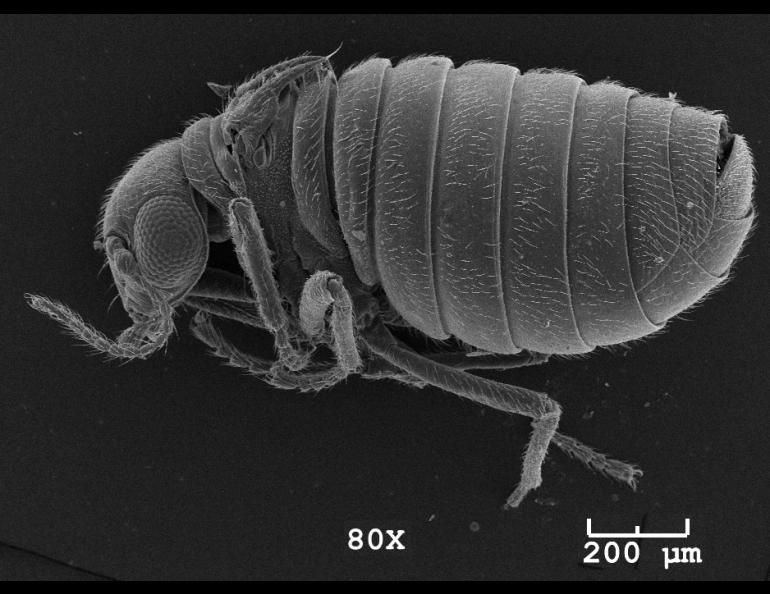

The tiny animal, now known as Caurinus tlagu, was different because it is a species new to science. It hops in a small group of snow scorpionflies that includes just one other species.

Sikes, who shared with Stockbridge the honor of naming the insect with the Tlingit word “tlagu,” meaning ancient, was at first so baffled that he posted its photo on Facebook. He hoped his entomologist friends might have a clue.

One did. Michael Ivie recognized that the elusive insect resembled one studied by another colleague, Loren Russell of Oregon. In the late 1970s, Russell wrote his dissertation on a similar creature he found in Oregon. In exquisite detail, Russell wrote of his many observations of the insect, such as its appetite for a leafy liverwort plant and that it had no apparent predators in the miniature rainforest jungle of spiders and psuedoscorpions. He also documented its ability to cement its eggs to leaves with a dark lacquer, its lifespan of more than one year and its peculiar tendency to headbutt its food.

In May, Russell traveled to Prince of Wales Island with Sikes and Stockbridge. In the lush greenery of the sample sites, Russell demonstrated how to collect the insect. Like a museum curator dusting a display, he wristed a soft brush on the greenish portion of stumps with a collection cloth beneath. Though Stockbridge had only gathered 37 of the creatures in her initial sampling (along with 10,218 beetles), the Alaska entomologists now know how and where to find lots of Caurinus tlagu.

The amber, wingless insect living on Prince of Wales Island is quite similar to the one that so fascinated Russell in the 1970s, but is separated by more than 650 miles. Sikes and Stockbridge found that the Alaska version of the insect is a new species because of DNA sequences. The Alaska males also have fewer lenses in their compound eyes and the Alaska females have a shallower notch at the end of their wee abdomens.

Caurinus tlagu fascinates the scientists not just because it’s a new species, which is cool on its own, but because it belongs to a group that has been around so long.

“This really is an ancient insect,” Russell said over the phone from Oregon. “It was well into the age of the dinosaurs, the Jurassic, when it split off (from other similar insects). That it was there on Prince of Wales Island through periods that were so heavily glaciated suggests that there were little pockets of forest, maybe stunted spruce surrounded by ice, like in Glacier Bay.”

Russell pictures the flea-size insect underfoot at campsites used by the first Americans, the adventurous souls who might have paddled kayaks to the New World thousands of years ago.

“It’s a signal that there were patches of coastal forest that might have helped people migrate,” he said. “That’s what’s exciting to me.”

Sikes sees Caurinus tlagu as a relic creature from a world millions of years ago, not unlike the horseshoe crabs he saw on a recent visit to beaches on the Delaware coast.

“We find new species all the time,” he said. “But we don’t find such unusual new species belonging to groups dating back to the Jurassic.”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.