Twenty weeks through the heart of Alaska

"It is a very remarkable fact that a region under a civilized government for more than a century should remain so completely unknown as the vast territory drained by the Copper, Tanana and Koyukuk Rivers."

So wrote Henry Allen in a government report on his muscle-powered journey from the mouth of the Copper River to the mouth of the Yukon, from where he returned by steamship to the civilized 48. Pushing on when Native guides wouldn't join him for fear of starvation, Allen and a few tattered comrades traveled from near present-day Cordova up to what is now Bettles. They then turned around and then beat winter to St. Michael, where they jumped the last boat for San Francisco.

The U.S. Army lieutenant executed the journey from spring equinox to early September in 1885, completing an epic his commanding officer, General Nelson Miles, compared to the Lewis and Clark expedition of 80 years before.

After he visited Alaska one year before to check the progress of another explorer, Allen proposed the expedition, which he detailed in the compelling "Report of An Expedition to the Copper, Tanana, and Koyukuk Rivers, in the Year 1885, for the Purpose of Obtaining all Information Which will be Valuable and Important, Especially to the Military Branch of the Government."

Allen's mission was to map and describe the uncharted core of the immense land recently purchased from the Russians. He was also to report on the Native people and the threat they might pose to white settlers who would someday arrive.

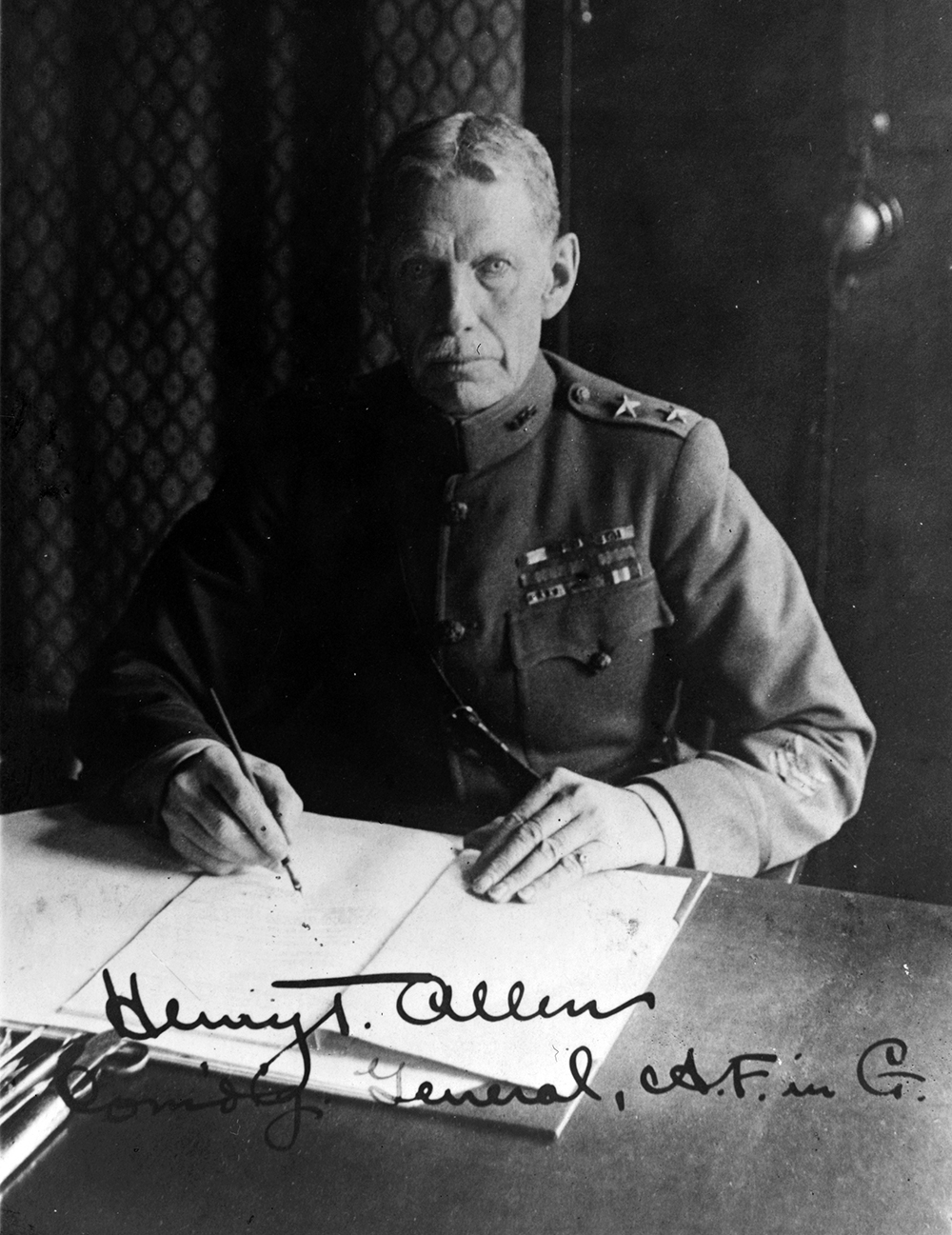

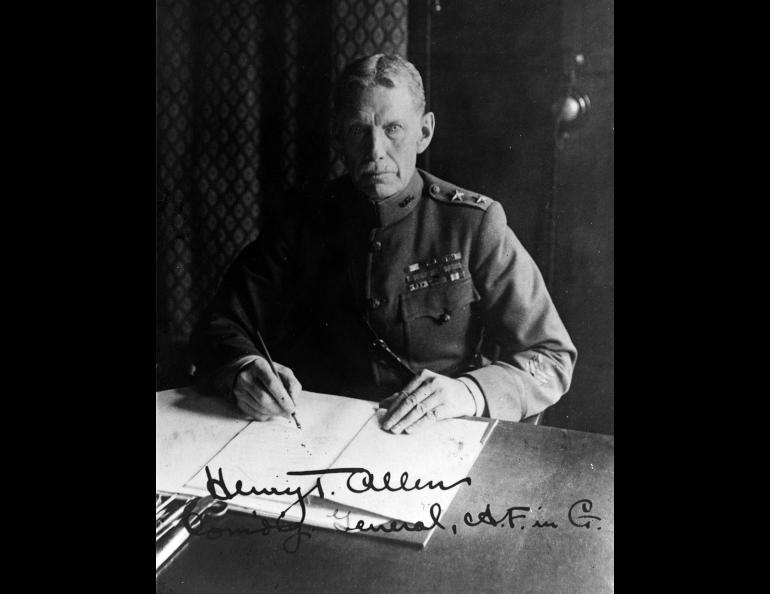

Allen, who graduated from West Point in 1882, ended his career as a general and commander of occupation forces in Germany after World War I. He traveled the world as a military attaché to Russia and Germany and was a military governor in the Philippines. But one wonders if his most memorable adventure was splashing his way through Alaska during the summer he turned 26.

Despite the $2,000 they were endowed, Allen and the few men who joined him were required to "live off the country." Working their way up the rotting ice of the Copper River in late March with soon-to-be-useless sleds, Allen "made the first attempt at eating the entrails of an animal — a porcupine. They were not relished then as they were at a later stage."

At times guided by Natives who were themselves famished while waiting for the return of salmon, Allen never stopped for long. His small group sniffed out and raided caches and bartered for food with whomever they encountered. His partner Private Frederick Fickett detailed much of the group's hunger in his journal, including this passage about moose scraps found on the ground at a Native camp near present-day Chitina: "These, that neither they nor their dogs would eat, we were forced by hunger to gather up and make a meal on. This is it. Allen's birthday, and he celebrated by eating rotten moose meat."

Incredibly, Allen reported that he and his traveling partners never saw a moose or caribou in covering more than 1,500 river-valley miles. Allen attributed the lack to the animals being hunted out. His report has many passages similar to the one in which he describes a Native guide bringing back one snowshoe hare for a party of nine men. Hares were the number one subsistence food on the trip.

"For days and weeks almost our sole dependence was on these little animals, and during a season when they did not possess a particle of fat."

When the protein finally came to Allen's party, as the salmon returned in June to Suslota Lake in the Mentasta Mountains, Allen walked away from them, obedient to his task and faithful that more food would appear in the unknown ahead. Many times he and his charges staggered into encampments to be saved by the meager amounts the Natives had to share. His men’s feet swelled and skin blackened from scurvy.

Even when hungry, Allen drew fine maps of the river country, which he traveled in Native skin boats or traversed on foot. He also noted the farthest north volcano — steaming Mount Wrangell — and described ice lenses and permafrost. He bestowed names on features like the Robertson River (for Sgt. Cady Robertson at his elbow) but always wrote the Native name for a river or mountain if it was evident.

Allen got to know Alaska Natives as few white men had. He adopted their footwraps (or went barefoot when paddling downstream), ate their food and coaxed some of them to guide him. He was frustrated with their "ignorance of methods of computing time" and disliked bartering with them, but admired their ability to survive.

In recommending what sort of U.S. forces might be sent to subdue these resourceful people if conflicts arose similar to recent skirmishes with the Cheyenne, Comanche and Sioux, Allen said the troops should be like the men who, unknown to him, would soon flood the country: "Each man should be chosen for his obedience, strength, endurance, and ability to live in a country where food is difficult to obtain . . . I know of no class of men so capable of fulfilling these conditions as mineral prospectors."

Since the late 1970s, the director of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks has supported the writing and free distribution of this column to news media outlets. This is Ned Rozell's 20th year as a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.