Where science and high adventure meet

Lonnie Thompson once spent 53 consecutive days at 20,000 feet, about the height of Mt. McKinley. While there, on an icefield in the Peruvian Andes, a fierce wind lifted Thompson’s tent. To prevent a 6,000-foot plunge off the mountain, he jabbed his ice axe through the tent floor.

“It was not a storm—this was the jet stream coming down and hitting the mountain,” Thompson said while visiting Fairbanks recently. “I spent the night in this collapsed tent, but at least it wasn’t moving because it had an ice axe through it.”

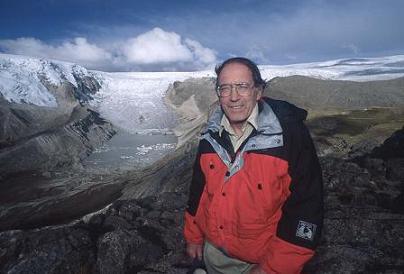

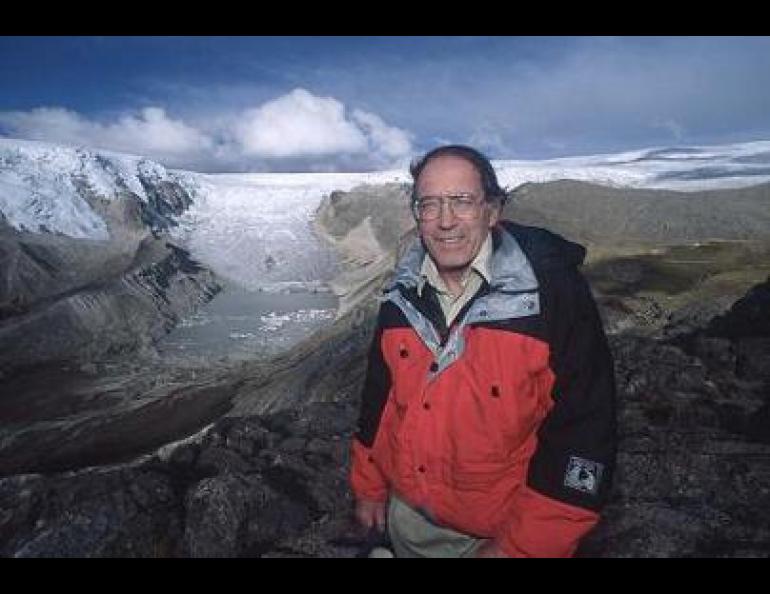

Lonnie Thompson’s adventures have taken him from Peru to Antarctica, from Greenland to China, and from Africa to Alaska. Though he is the current world record holder for most days spent living above 18,000 feet, he earns paychecks not as a mountaineer, but as a scientist.

Thompson extracts cores of ice from mountains and icefields all over the world, and the information in those cores has answered – and raised – many questions about Earth’s past climate. This research has gotten him a breakfast invitation at the White House, and he was recently available for an interview in Fairbanks while attending a conference.Thompson is the 55-year-old leader of the ice-coring group at the Byrd Polar Research Center in Columbus, Ohio. During the past 28 years, he’s completed 47 expeditions to high, cold places in 15 countries, getting drills to mountaintops and bringing home ice cores that hold clues about Earth’s ancient atmosphere, sometimes going back as much as 700,000 years. The highest place from which they have pulled a core is 23,500 feet, from Dasuopu, Tibet. In summer 2002, they drilled to bedrock and retrieved a 1,500-foot plug of ice from a saddle between the summits of Mt. Bona and Mt. Churchill in the St. Elias Range.

Ice cores can tell researchers a region’s precipitation history, trends in climate, what pollen of plants was floating around, and sometimes the fire history of a region. Thompson has done much of his work between the Arctic Circle and the Antarctic Circle. In the 1970s, he became intrigued with an ice cap high in the Andes Mountains of Peru. A few years and many obstacles later, he and his teammates were drilling the surface of Quelccaya ice cap.

They extracted two 525-foot ice cores from the tropical glacier in 1983 and found a record of the equatorial precipitation and temperature shifts dating back to A.D. 470. Their results showed radical temperature swings corresponding to a Medieval warm period and three centuries of cold known as the Little Ice Age ending around 1880. Before Thompson’s work, scientists had thought those climate swings were felt only at higher latitudes.

Thompson and his colleagues now have more than four miles of ice core stored in Ohio State’s cold room at -22 degrees F. With the extreme melting he has seen during his career, Thompson is scrambling to collect and preserve more.

“When we first started this, we didn’t realize how fast some of these archives are disappearing,” Thompson said, giving the example of Mt. Kilimanjaro in Africa, which has lost 80 percent of its ice cover since 1912. “If you continue that curve, in the next 15 years all the ice on Kilimanjaro will be gone.”

Thompson will not rest while the ice is still there. This July, he’s headed back to the Quelccaya ice cap in Peru to measure its rapid melt. In August and September, he’ll travel to the Himalayas to scout for a place to drill the following year. Because the ice is melting so rapidly, he’s seeking funding from nontraditional sources, such as Land’s End clothing founder Gary Comer, who provided funds for post-graduate researchers with Thompson’s group. Funding from the National Science Foundation, a government agency that often provides support for such studies, is too slow, Thomson says.

“We’ve got to get these archives before they’re gone,” he said. “The ice is disappearing faster than we can go through the NSF process.”