A wrinkle beneath the icy face of Alaska

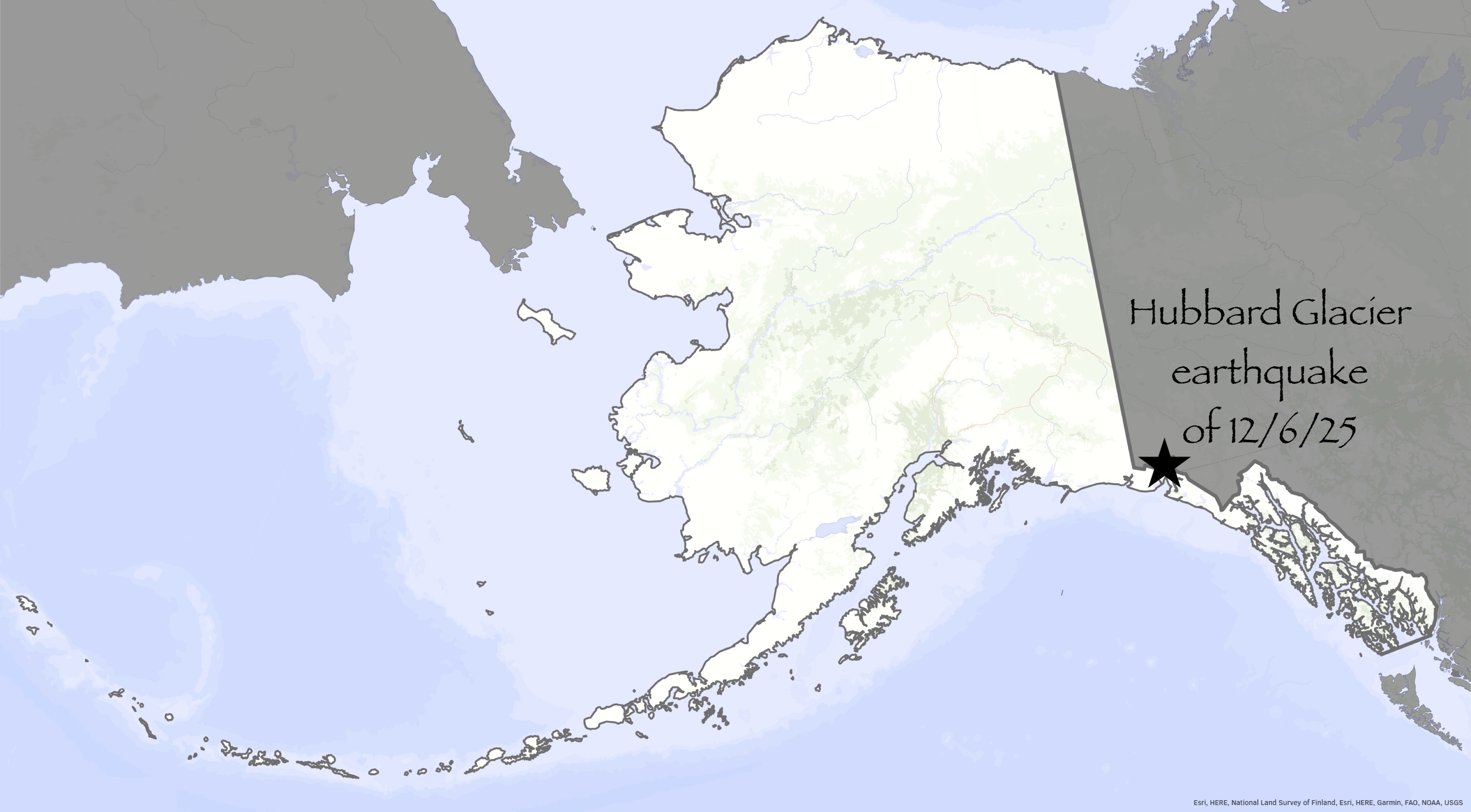

A few days ago, the forces beneath Alaska rattled people within a 500-mile radius: A magnitude 7 earthquake ripped under Hubbard Glacier.

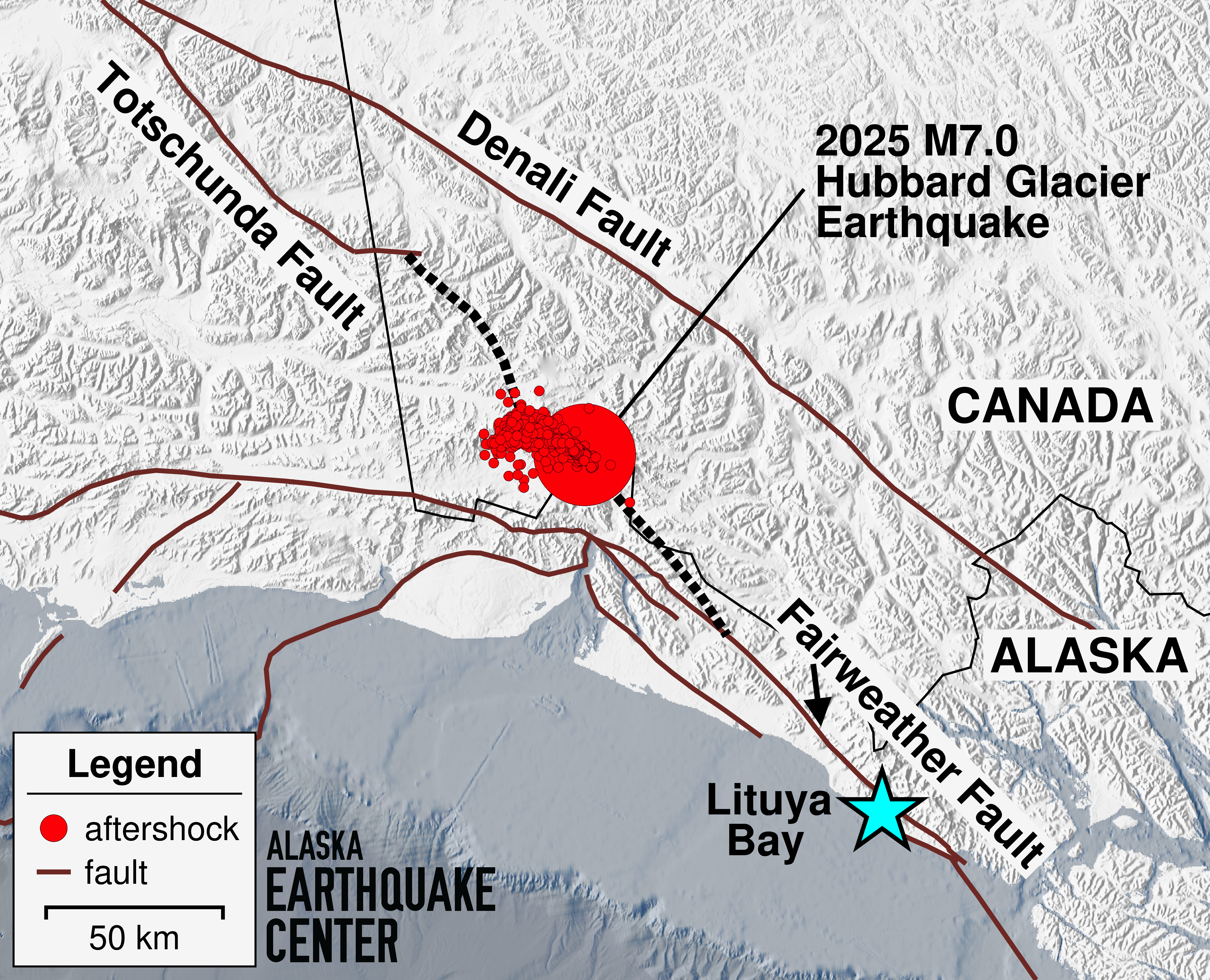

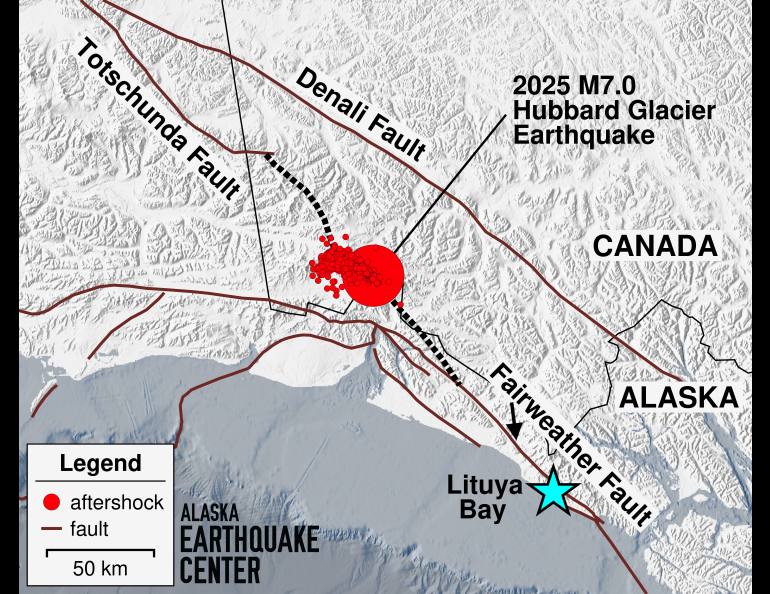

The earthquake’s main shock and aftershocks have revealed something else — a possible slash across the face of Alaska long buried by glacial ice, a feature that professionals speculated upon decades ago.

Before getting to that, here’s a review from State Seismologist Michael West on the significance of an earthquake this big:

“We get so numb to magnitude scale in this state,” he said at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, where he works for the Geophysical Institute. “A magnitude 7 is one hell of an earthquake. Put that in Afghanistan, it would kill 10,000 people.”

So far, there are no reports of injuries in the restless corner of Alaska near the fishing town of Yakutat. Nor in the bordering high country of the western Yukon or British Columbia.

But some glaciers now wear a new coat of fallen rock.

“This is violent,” West said. “It shook loose landslides all across the region.”

The earthquake and its more than 2,000 aftershocks have caught the attention of scientists who have over the years connected the dots between massive fault systems separated by some of the greatest icefields on Earth.

All those individual shocks are the science version of pointillism. That painting technique, developed by two French artists in the late 1800s, features the singular application of dots to a canvas that in time reveals a larger picture.

The Hubbard Glacier earthquake of Dec. 6, 2025 has painted a coarse line beneath the ice. Some researchers think it may trace a “connector fault” between established cuts in the thick planetary crust.

Those slices in the Earth are visible in some cases. The Denali Fault, for example, frowns across middle Alaska as a linear, sometimes ice-filled trench between mountains. And the Fairweather Fault, a northern extension of the San Andreas that slashes through the back of Lituya Bay. The Fairweather was responsible for an earthquake that shook a mountaintop into that bay in 1958, causing a 1,700-foot splash wave — still the highest ever recorded.

Looking at the records of shakes large and small from the Dec. 6 earthquake, scientists see a pattern that has intrigued them.

“That jaggedy feature, I would call it the Connector Fault,” said Peter Haeussler, a recently retired U.S. Geological Survey scientist emeritus.

Haeussler was so excited about the development that he answered an inquiry while sailing aboard his 45-foot sailboat upon Mexico’s Sea of Cortez.

He spoke about noted geologists including Don Richter and George Plafker who speculated many years ago that two of Alaska’s major fault systems had to be invisibly connected beneath the great icefields where Southeast Alaska hooks on to the rest of the state. They had a niggling but couldn’t get up there to check.

“There’s all this territory between the Totschunda (a mapped offshoot of the Denali Fault that ruptured in November 2002) and the Fairweather Fault. But it’s under the ice, it’s at high elevation, and it’s dangerous,” Haeussler said.

Julie Elliott, a research professor from Michigan State University, was a graduate student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in 2011 when she studied the creeping movement of the region using many high-precision GPS observations.

In a paper she wrote as part of her Ph.D, Elliott included a modeled Connector Fault beneath the ice, following the straight lines of glaciers that scientists had speculated would be the likely pathway of a hidden fault.

“I’ve seen some preliminary relocations of the aftershocks and they line up quite well with the location of my model fault,” Elliott said. “The geologists’ idea that a fault could lie beneath the ice fields was a good one.”

As more aftershocks paint the Alaska map one point at a time, West is hesitant to yet declare the recent earthquake the smoking gun that has revealed the Connector Fault.

He — as well as the other scientists interviewed — described that part of Alaska as a “geologic train wreck.” There, the Yakutat microplate, a thick chunk of Earth’s crust, slides along and collides with Alaska.

This causes earthquakes along strike-slip faults (ones with energy flowing both ways, like trucks zooming past each other on a two-lane highway) like the Fairweather. Over the years, the tectonic action has shoved up some of the greatest coastal mountains on the planet, among them 18,008-foot Mount St. Elias and 15,300-foot Mount Fairweather.

“This area really should be super-complicated,” West said.

West thinks the Hubbard Glacier earthquake has indeed revealed the southern end of a connector fault, but the scatter of the earthquake signals toward the northwest has his gut telling him there is another, smaller fault involved.

“This may be a little dirtier than a 50-kilometer fault ripping cleanly.”

Geologists would love nothing better than to get their boots to the site of the Hubbard Glacier earthquake right now. Once there in that quiet, cold country, they would look for the same tears along the ice-and-rock surface that showed for 200 miles after the 2002 Denali Fault earthquake.

A few complications exist: The Hubbard Glacier earthquake happened in the fleeting light of December beneath a crevassed ice field that is 67 miles away from the nearest fishing town.

“I am a bit disappointed that the earthquake happened during the winter,” Elliott said.