You can fool some of the ravens some of the time

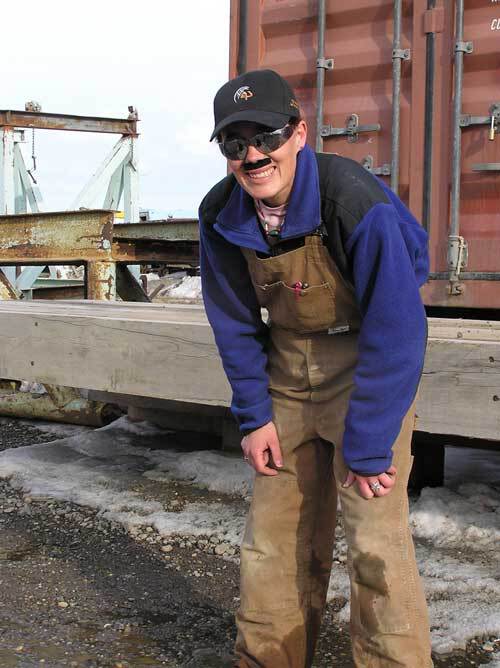

Stacia Backensto has upped the ante. The biologist and UAF student who studies ravens on Alaska’s North Slope has dropped her fake moustache and has taken more drastic measures to not resemble herself when she tries to recapture the birds.

She now wears a beard made of fuzzy fabric, a wig, and she duct-tapes pillows around her midsection to play the most fun role of her graduate-student career, that of “a grumpy old oilfield worker.”

“By the time I got around to the beard and the duct-taping of the pillows, I found myself with a 30-minute costume prep time before trapping,” said Backensto, a Ph.D. student with UAF’s Regional Resilience and Adaptation Program. “It was kind of like getting ready to go onstage.”

Backensto, studying how oil and gas development activities affect ravens, needs to hide her identity from the six or so ravens she has captured before in Prudhoe Bay.

“When I don’t have my disguise on they are a bit obnoxious,” she said, sometimes diving at her or making aggressive noises while pecking hard on metal posts in her vicinity.

She occasionally needs to recapture birds that have lost their transmitters in order to follow them around the oilfields at Prudhoe Bay. She doesn’t think she can do it without her elaborate disguise, which she accentuates by trying to walk differently.

“It actually fooled a few birds that knew me pretty well,” she said. “In 50 percent of the cases, birds that knew me seemed to be confused.”

The dean of raven studies in the U.S., Bernd Heinrich, a professor emeritus at the University of Vermont, wrote about wearing a kimono to fool ravens in “Mind of the Raven; Investigations and Adventures with Wolf Birds.”

Heinrich once kept ravens he had captured in a large pen. After a year of living in captivity, they became comfortable with him coming in to feed them, though the birds were skittish around everyone else. Out of curiosity, he saw how ravens reacted when he wore a kimono.

“When I wore it, they flew up (in alarm) at fifteen yards, but it didn’t fool them for long,” Heinrich wrote. “After my thirteenth approach in the kimono, they again allowed me to get next to them.”

John Marzluff, a professor at the University of Washington and the author of “In the Company of Crows and Ravens” did a study on the university campus where his research team captured and tagged the raven’s close relative, the American crow. First, Marzluff’s crew wore latex masks of Dick Cheney and a caveman around the Seattle campus and noticed that crows had no reaction to them. Then, the researchers captured seven crows with net guns while wearing the caveman mask. From then on, crows harassed people wearing the caveman mask, swooping and scolding that person. Dick Cheney walked around unmolested.

“We did this experiment over a year and half ago, and to this day crows are still responding to this caveman face,” Marzluff said.

The crows learned to associate the caveman with something bad in three ways, Marzluff said. The seven birds captured by the caveman remembered it, but other crows learned from either watching the caveman capture the birds or from observing caveman-savvy crows scolding the person in the mask when he or she appeared in campus crowds. For a social bird that interacts with humans, it is perhaps an advantage to remember the bad eggs, Marzluff said. He said crows and ravens are unique in this way.

“I don’t know of other birds who do this in the wild,” he said.