Unmanned aircraft used to survey ice for whalers

Researchers used an unmanned aircraft to map the sea ice north of Barrow in April as part of a cooperative effort between the Native community of Barrow and the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Whaling captains want to know the safest route across the ice to reach leads where bowhead whales will pass by. Every year, the community of Barrow uses hand tools to build trails that extend up to several miles across sometimes very rough sea ice. Knowing the most efficient route through the ice ahead can save labor and improve safety for hunters on the landfast ice. If the ice is too thin and poorly grounded to the ocean floor, it may break off during severe wind events or ocean currents, a potential hazard for people on the ice.

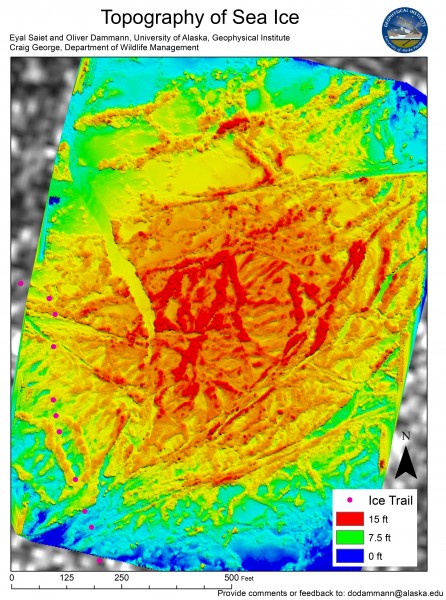

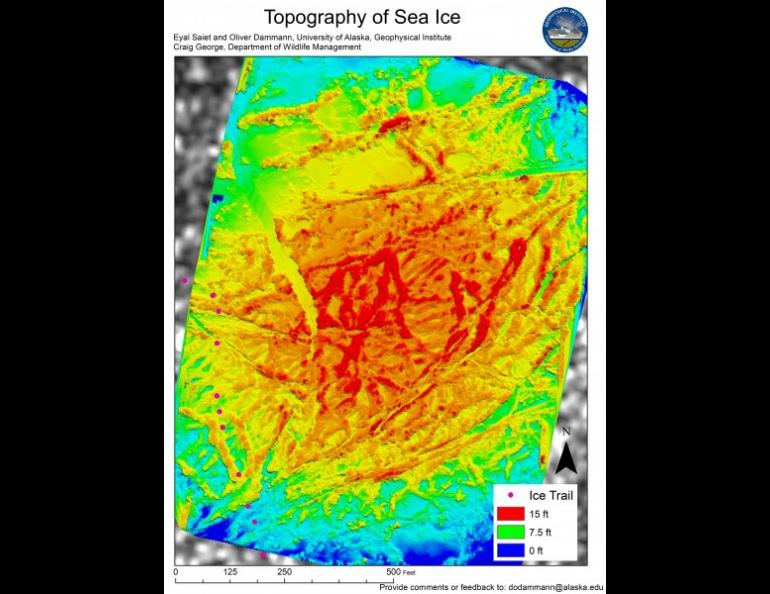

Some parts of the ice are crumpled and folded, extending down to the sea floor, while other areas are smoother and easily travelled. Craig George of the North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management and whaling captains Harry Brower and Eugene Brower were interested in more information about the topography and geography of the constantly changing sea ice.

UAF scientists Hajo Eicken, Andy Mahoney and the sea ice group at UAF have worked with the Barrow community for years to understand and monitor the sea ice and map the trails across it. The sea ice group installed a radar and a webcam in 2007 to provide a continuous view of the ice from a vantage point in Barrow. While these provide important information to both scientists and locals, the view from the side and the resolution at a distance limit their usefulness. Satellite data is available, but expensive.

Doctoral student Dyre Oliver Dammann and Eyal Saiet, a staff member for the Alaska Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration and masters student in remote sensing, decided to try mapping the ice using a Ptarmigan, a small hexacopter designed and built by UAF electrical engineering student Ben Neubauer. This aircraft is particularly handy for short flights and experimenting with new instruments. The NovAtel company sponsored a small and highly accurate GPS unit, and the unmanned aerial vehicle was fitted with this and a high-quality camera.

John Roberts, an experienced helicopter pilot, flew the UAV in a grid pattern 400 feet over a section of ice about 200 by 800 meters. It was 5 degrees with a wind, making it difficult to keep his fingers warm, but Roberts was able to complete the grid after three pauses to change the UAV’s batteries.

The Barrow community and Ukpeagvik Iñupiat Corporation’s UIC Technical Services provided transportation for the people and gear, including a cooler with an electric blanket to keep batteries warm, generators and a bear guard.

After the flights, Saiet used a technique pioneered at UAF’s Geophysical Institute for Arctic applications, called structure from motion, to create an accurate three-dimensional map of the surface. He was able to print copies and share them with the whalers. Maps also can be uploaded to cell phones, iPads and the like.

Saiet and Dammann hope to try again next spring, this time with a fixed-wing UAV that can fly longer and carry the equipment before its battery needs replacing.

Sue Mitchell, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-5823, sue.mitchell@alaska.edu

Eyal Saiet, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-455-2029, ejsaiet@alaska.edu

Oliver Dammann, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-5648, dodammann@alaska.edu