A group of University of Alaska Fairbanks faculty, students and staff has been conducting Arctic fieldwork in Utqiagvik since mid-April to measure snowmelt, but the melt only started in mid-June.

This is an exceptionally late melt year.

The Snow Albedo Evolution in the Arctic team, or SALVO, has been working hard through the midnight sun, which never sets in Utqiagvik. The group includes Jennifer Delamere, Matthew Sturm, Melinda Webster, Anika Pinzner, Phillip Wilson, Ema Mayo, Serina Wesen, Hannah Chapman-Dutton and Owen Larson, all affiliated with UAF. The team also includes David Clemens-Seawall from Dartmouth and David Shean with the University of Washington.

"The goal of the project is to understand the mechanisms that control the speed with which the landscape clears of snow and therefore absorbs solar radiation,” said Sturm, group leader for the Snow, Ice and Permafrost Group at the UAF Geophysical Institute.

The team began this year’s fieldwork in Utqiagvik in mid-April to set up four snowmelt sites: two on sea ice and two on tundra. These initial pre-melt measurements can be compared to the May and June melt.

The team returned to Utqiagvik on May 15 and initially planned to leave on June 15 based on when the snow melted in previous years.

The group expects to still see snow in Utqiagvik on the summer solstice. Due to this year’s late melt, the team will have members stay until the end of June.

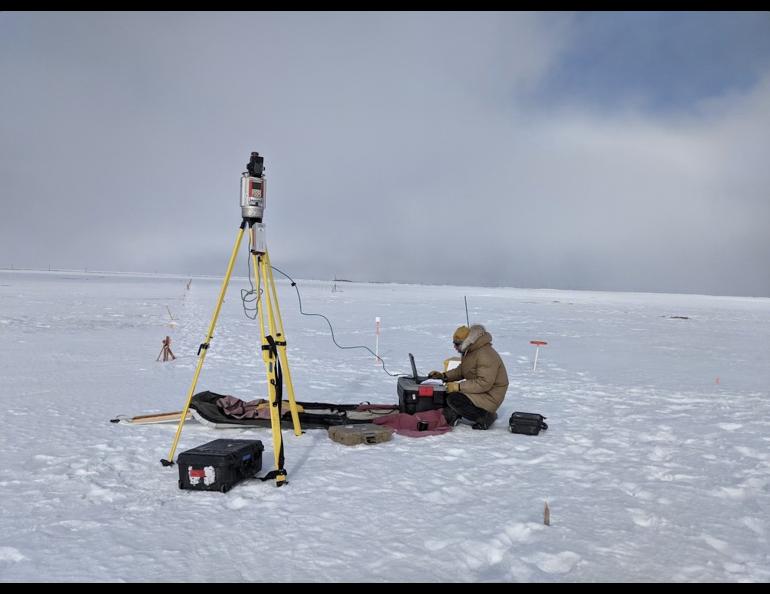

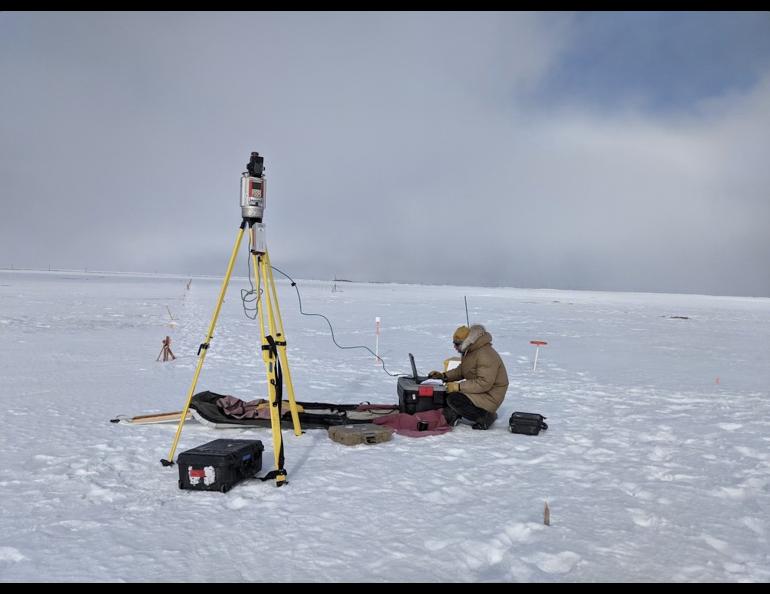

Melt ponds have begun forming on the sea ice, causing it to break up, but the group is still able to carefully snowmachine to a Chukchi Sea study site. Key activities include digging snow pits, measuring snow grain size, gathering basal snow temperatures and snow water equivalent, measuring albedo and incoming radiation, using GPS-enabled snow depth probes, photographing sites, taking snow samples to find impurities and making terrestrial lidar scans.

The team is not alone in the Arctic, with polar bears, migratory birds, seals, caribou, and other Arctic life keeping them company.

“By taking all of these measurements, we are trying to understand what drives the change from a completely white, snowy surface to much darker summer surfaces like tundra or sea ice melt ponds,” Pinzner said.

Even though snowmelt has occurred earlier in more recent years, this year’s delayed late snowmelt is an anomaly related to a changing Arctic climate.

The project is sponsored by the Atmospheric Sciences Research Program of the U.S. Department of Energy. The team would like to recognize that this ongoing research is occurring on Inupiaq land and could not have been completed without the wisdom and generosity of the Utqiagvik community.

–

Serina Wesen is the education and outreach designer for the Geophysical Institute’s Snow, Ice and Permafrost Group.