And the mountains shrugged...

The Denali Fault earthquake jiggled the Alaska Range with enough force that the mountains gave off an acoustic signal detected in Fairbanks, scientists recently discovered.

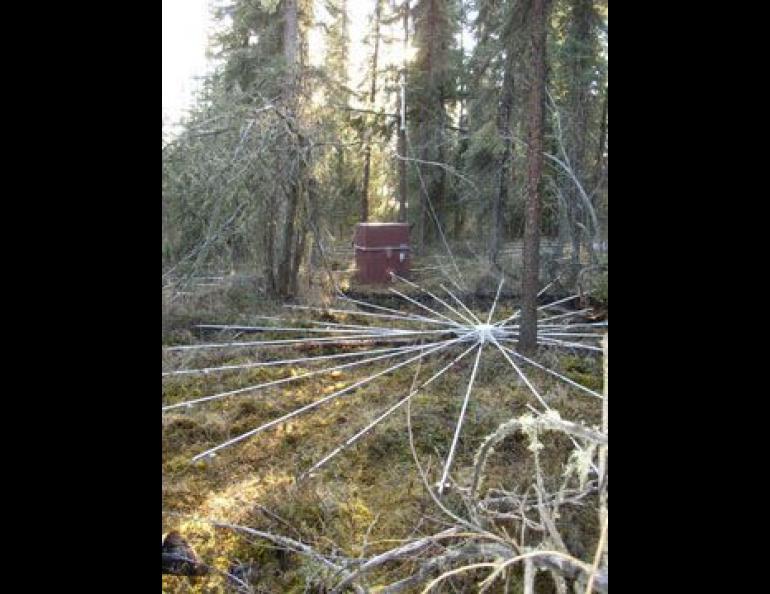

John Olson, Charles Wilson, and Daniel Osborne heard the mountains move with microphones installed in the woods on University of Alaska land. The microphones are part of an infrasound system of the sort used to detect nuclear explosions. Olson is a physics professor and Wilson is a professor emeritus at UAF’s Geophysical Institute, and Osborne is a project engineer there who turns their ideas into reality.

The magnitude 7.9 Denali Fault earthquake of Nov. 3, 2002 ripped a scar across 210 miles (340 kilometers) of Alaska. The ground along the Denali Fault moved as much as 29 feet (8.8 meters) during the earthquake. The sudden jerk of the mountains shoved large parcels of air and created an acoustic signal in the same way a speaker cone produces sound.

“Imagine Mt. Hayes and Mt. Hess moving 30 feet,” Olson said, referring to two Alaska Range peaks visible from Fairbanks. “The mountains were pushing on air, creating pressure waves.”

The song of the Alaska Range was too low for people to hear, but the sensitive microphones at UAF picked it up. Olson decided to check his instruments’ data after talking to another scientist at a conference in Vienna. Nicolas Brachet, an official with the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization, told Olson about a similar signal received at Manitoba, Saskatchewan on November 3rd. The Denali Fault earthquake had shaken the entire Rocky Mountain system through Canada, Brachet said.

Once back in Alaska, Olson told Wilson about the shaking of the Rockies. Wilson then checked the recordings of the Fairbanks infrasound network and saw that their microphones had captured the shudder of the Alaska Range. The microphones recorded the entire earthquake sequence, from the ground shaking to the delayed arrival of the acoustic wave. The microphones are sensitive enough that earthquake motion (or even the footsteps of a nearby moose) will trigger them, as will a reduction in atmospheric pressure if the microphones are lifted, which also happened during the earthquake.

Using the digital graph of the microphone recordings, the scientists were able to clock the speed of the earthquake’s rupture of ice, rock and tundra and the slower acoustic signal. While the earthquake ripped through the Alaska Range at about 2 miles (3.3 kilometers) per second, the acoustic wave took about 14 minutes to reach Fairbanks from the Alaska Range, traveling about 990 feet (300 meters) per second.

In addition to monitoring the sudden movement of mountains, the UAF infrasound instruments have detected storm surges in the Gulf of Alaska, the rumblings of volcanoes, meteors screaming into the atmosphere, and even the aurora. Infrasound waves are sound waves with a frequency below 20 Hertz, which is about the lowest frequency detectable by the human ear. Infrasonic signals move around the planet in slow, concentric circles. An infrasound wave from a 1980 nuclear explosion in China took more than six hours to get to Fairbanks. The wave registered again 37 hours later as it completed another lap around Earth.

The UAF scientists have installed the network of microphone arrays in the woods surrounding the campus to test the best designs. Sixty such arrays will be set up around the world by countries whose leaders agreed to ban the testing of nuclear bombs in the atmosphere. Wilson, Osborne and colleagues have traveled to Antarctica to set up an infrasound station for international monitoring. Closer to home, their microphones are capturing many of the world’s vibrations, including those generated by mountains that move.