What’s in an Alaska name?

I once asked a snowmachiner heading out on a trail from Nome where he was going.

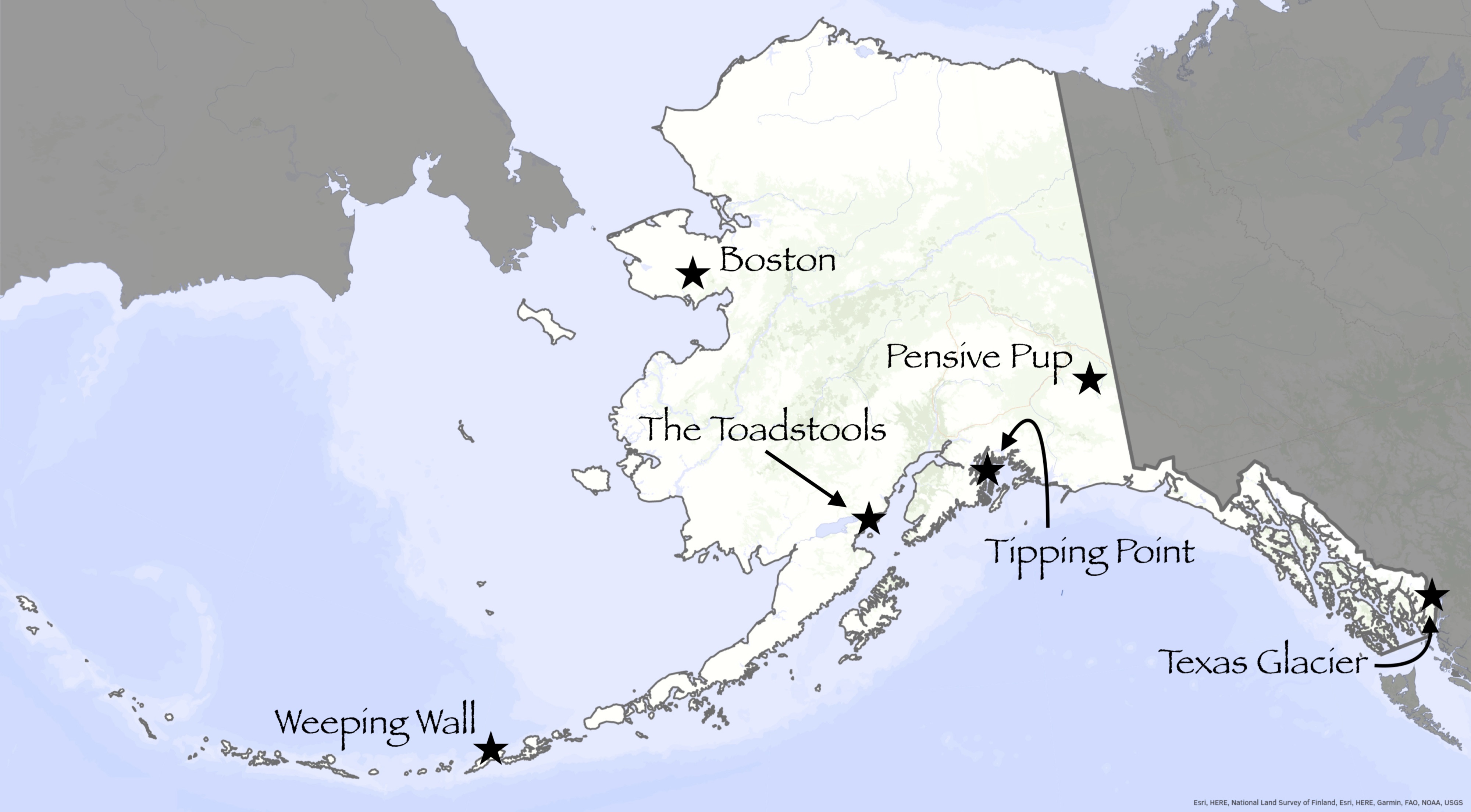

“Boston,” he said before speeding off.

Not knowing of any Boston within 3,600 miles, I thought I had misheard him.

But later that day I looked at a map of the route of the All-Alaska Sweepstakes dog race that started the next day (the last race was held in 2008). In the middle of the course was a checkpoint: Boston, Alaska.

A day later, I walked into the Nome library to see if it had U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper No. 567, also known as Donald Orth’s Dictionary of Alaska Place Names.

The 6 1/2 –pound blue book (not recommended for backpacking) listed Boston as a stopping point on the old Nome-to-Candle Trail. A prospector named it sometime before 1902, for the nearby Boston Creek. Like so many other places in Alaska, the name stuck but the place didn’t.

On the same trip, which involved two weeks of snowmachining on Alaska’s western coast, we passed through Hamilton, New Hamilton, Nokrot, Klikitarik, Barrabora, Egavik, Walla Walla, Topkok, Belmozok and Ikpek, Alaska. We didn’t see a soul in any of them. And at most of those places we didn’t even see buildings.

I then looked up the entry for the town in which I was sitting. “Nome” came from the nearby Cape Nome, which a mapmaker wrote after misinterpreting “? Name” written on a nautical chart in the 1850s.

An 1880 census map of the lower Kuskokwim River shows the villages of Shineyagamute, Kuskigamute, Iliutagamute, Chimiagamute, Apokagamute, Shevenagamute, Kakhuiyagamute, Akooligamute and Mumtrekhlogamute, the latter of which is now known as Bethel.

Mumtrekhlogamute disappeared from the current map of Alaska when two priests of the Moravian church set up a mission there in 1884. They changed the name to reflect a Bible passage: “And God said unto Jacob, Arise, and go up to Bethel.”

A good number of current names on the Alaska map are the result of white explorers from England, France, Russia and the Lower 48.

But some local names endure. Most names beginning with a K are Native in origin —including Koyukuk, Kuskokwim, Kobuk, Kiska, Kipnuk, Katmai, Kivalina, Kotlik, Kiana, Ketchikan, Koyuk, Kuparuk, Kuskulana and Kodiak.

In the late 1800s, gold seekers named everything they encountered, often for flora and fauna (including 67 Willow creeks and 63 Bear creeks).

Since government geologists and explorers also mapped Alaska at a time when prospectors were crawling all over it, many of the miners’ names remain.

There are only eight places named for Alaska, including the Alaska Range, the Alaska Peninsula and the Gulf of Alaska. However, gold diggers named 36 features for California (including more than 26 California creeks).

Even Texas, with 10 namesakes — including a glacier — appears on the map more times than Alaska.

The 40,000 entries in Orth’s book also might help you name your garage band. Potentials include Tipping Point, Mosquito Flats, Ptarmigan Drop, Noisy Passage, Witches Cauldron, Weeping Wall, The Toadstools and Pensive Pup.