Farewell to the Wizard of the GI Machine Shop

Larry Kozycki never liked attention, but he was too talented to avoid it.

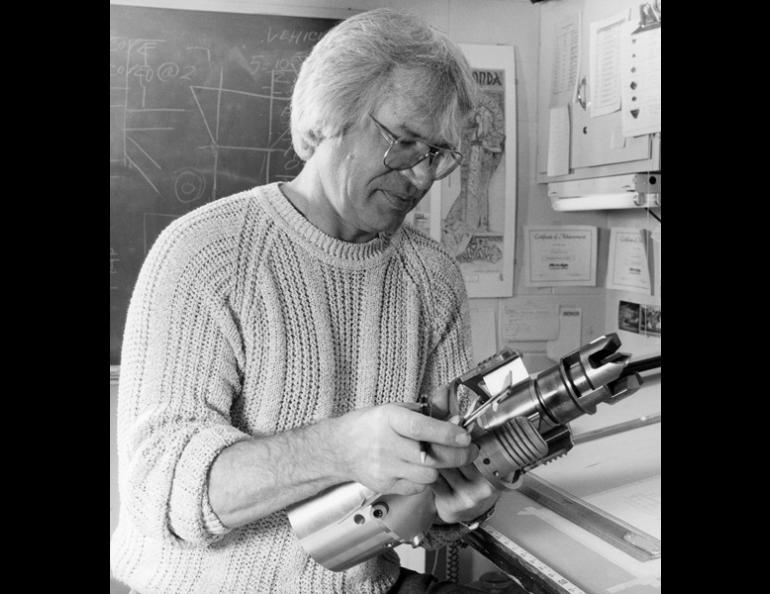

As supervisor of the machine shop at the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Kozycki's job was to take fuzzy ideas from scientists and transform them into precision instruments. Kozycki died of cancer the morning of October 24, 2001. He was 56.

For two decades, scientists visited Kozycki when they needed a tool, machine, or part they could not get elsewhere. He solved problems for dozens of scientists by sitting with them in his basement office, asking precise questions, then designing obscure scientific instruments. Kozycki's inventions included a drill bit that penetrated the Greenland ice cap and two machines that pluck tiny bones from salmon fillets.

"Larry was a rare combination of talents," said Geophysical Institute Director Roger Smith, a space physicist who uses Kozycki's creations for his experiments in Antarctica and the Arctic. Smith said Kozycki combined the vision of an engineer with the skills of a machinist and the dedication of a perfectionist.

"I learned very quickly not to tell him how to make something, but to tell him what I wanted the instrument to do," said Dan Osborne, a project engineer at the Geophysical Institute. "He always did a better job than what I had in mind."

The last thing Kozycki made for Osborne was a calibrator for an instrument that picks up low-frequency vibrations from underground nuclear tests and other sources.

"Now we've got the only one in the world," Osborne said. "A researcher at Los Alamos looked at it and said, 'That thing's built like a Swiss watch.'"

"Larry would design something incredibly complex, do all the drawings, and when his shop assembled it, it would work. That doesn't happen often," said Eric Johansen, a machinist with UAF's Mechanical Engineering Department.

One of Kozycki's greatest achievements was the design and construction of a drill the Polar Ice Coring Office used to penetrate more than 10,000 feet into the Greenland ice cap. With the drill, scientists recovered an ice core with a record of volcanic eruptions and ancient atmospheres from the past 200,000 years. John Kelley of UAF's Institute of Marine Science was head of the ice-coring project in the late 1980s. When a prototype drill didn't work, he sought Kozycki.

"Without Larry, we would not have had a chance," Kelley said. "He could make sense out of the most complicated design you would give him, and he would never say no."

International Arctic Research Center Director Syun-Ichi Akasofu was Kozycki's supervisor when Kelley approached Kozycki about the drilling project. Akasofu, then director of the Geophysical Institute, asked Kozycki if he had ever made a similar drill.

"He told me he had not," Akasofu said, "But he asked me to let him try. Larry responded beautifully."

Scientists who approached Kozycki with a problem always came out of his office with more ideas than they carried in. He was opinionated and well read, and he delivered his views with dry humor. "I'll miss his unique perspective on machinery, the university, Fairbanks, Alaska, Ireland, Afghanistan . . .," said Richard Collins, an assistant professor of space physics and aeronomy at the Geophysical Institute.

Kozycki's creativity was not limited to work projects. Ned Manning, a machinist who turned many of Kozycki's designs into useful objects, gathered some of Kozycki's creations in a corner of the GI machine shop. Among them were a rubber-tracked device Kozycki designed for a motor-powered snowboard and a "gold-sucker" mining tool made from a weed-whacker.

"He had the ability to see in 3-D," Manning said.

His talent to envision what others could not is what made Larry Kozycki unique in the university environment of academics and scientists. He once explained to me what it was like to have an inventive mind.

"If you're in this trade, you don't call a repair person when something breaks," he said. "You lie in bed staring at the ceiling, and you keep turning the problem over and over again until you get it."