Flying Saucer Clouds

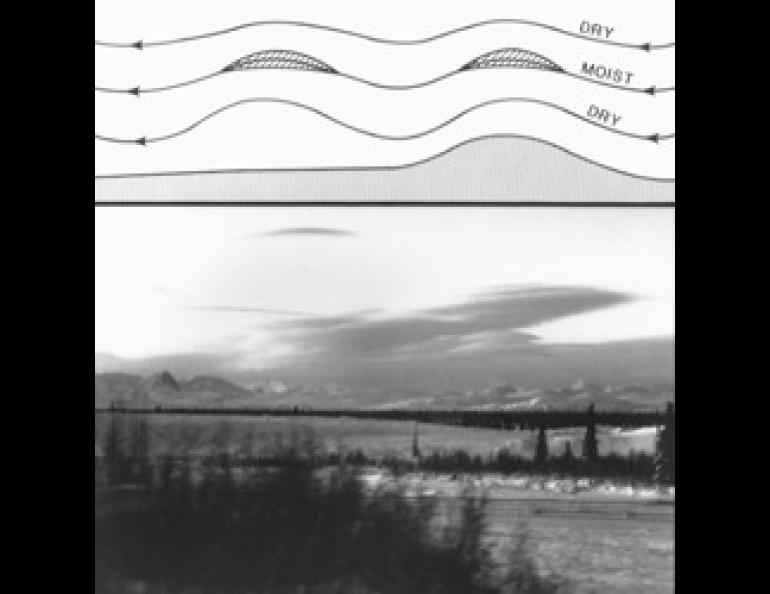

Although a few cases remain unexplained, the overwhelming majority of "Unidentified Flying Objects" (UFO's) are in fact identified rather quickly. Weather balloons, high altitude research balloons, the planets Venus and Mercury, and certain clouds have all produced UFO reports. (My own "UFO" turned out to be the reflection of a street light on a telephone wire.) The clouds most likely to produce flying saucer reports are lenticular clouds, which are common in Alaska in the winter.

Lenticular clouds, also known as wave clouds, are the most common member of an unusual class of clouds that remain stationary while the wind blows through them. They are normally generated by mountains, and almost every place in Alaska has enough mountains to allow wave clouds to be observed. They form because of two fundamental properties of air and water. First, when air is lifted and expanded, it cools. This is why temperature normally decreases with height. Second, as air cools, the amount of water it can hold decreases. If air that is already holding almost as much water vapor as it can hold is lifted and thus cooled, the water will condense out fairly promptly onto any particles that may be in the air, forming a cloud. If the air is dry to start with, the air has to be lifted much farther before a cloud forms. When the air descends again, it is warmed, and the cloud droplets evaporate.

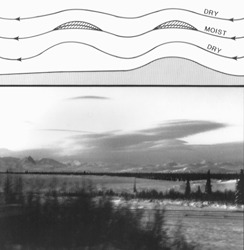

Now suppose a wind is blowing over a mountain, being lifted on the upwind side, descending and warming on the downwind side, and flowing in a smooth arc over the top of the mountain. If the humidity is high to start with, a solid ceiling of clouds will form, hiding the mountain. If the air is very dry, it may not be cooled enough to produce a cloud at all. But if most of the air is dry, with one or two thin layers that are wetter, clouds will form only in the wet layers. As the air rises, droplets form in the moist layer a little upwind of the mountain peak. These droplets are carried along in the wind as the air arcs over the mountain; as the air descends and warms on the lee side, the droplets evaporate. Individual droplets move through the cloud with the wind, while the cloud as a whole stays fixed over the mountain. If the air is flowing over the mountain in a smooth arc, the cloud will follow the shape of the air flow, and resemble an upside-down saucer. If there are several wet layers in the air, with drier layers between them, a wave cloud may form in each layer. The technical name for such a cloud formation, pile d'assiettes, actually translates as "pile of plates". Given that these plates in the sky are upside down, it is a very good description of their appearance.

Sometimes the waves started by a mountain range continue downwind of the range. When this happens, wave clouds may occur at regular intervals for a considerable distance to the lee of a mountain range. These lee waves are often visible on satellite photographs, and occur over large areas of Alaska when the winds are favorable.

When the ground is warm, heating of the lower air may destroy the smooth shapes of wave clouds. During winter and early spring, however, they occur fairly often. Keep your eyes open for flying saucer clouds this spring.