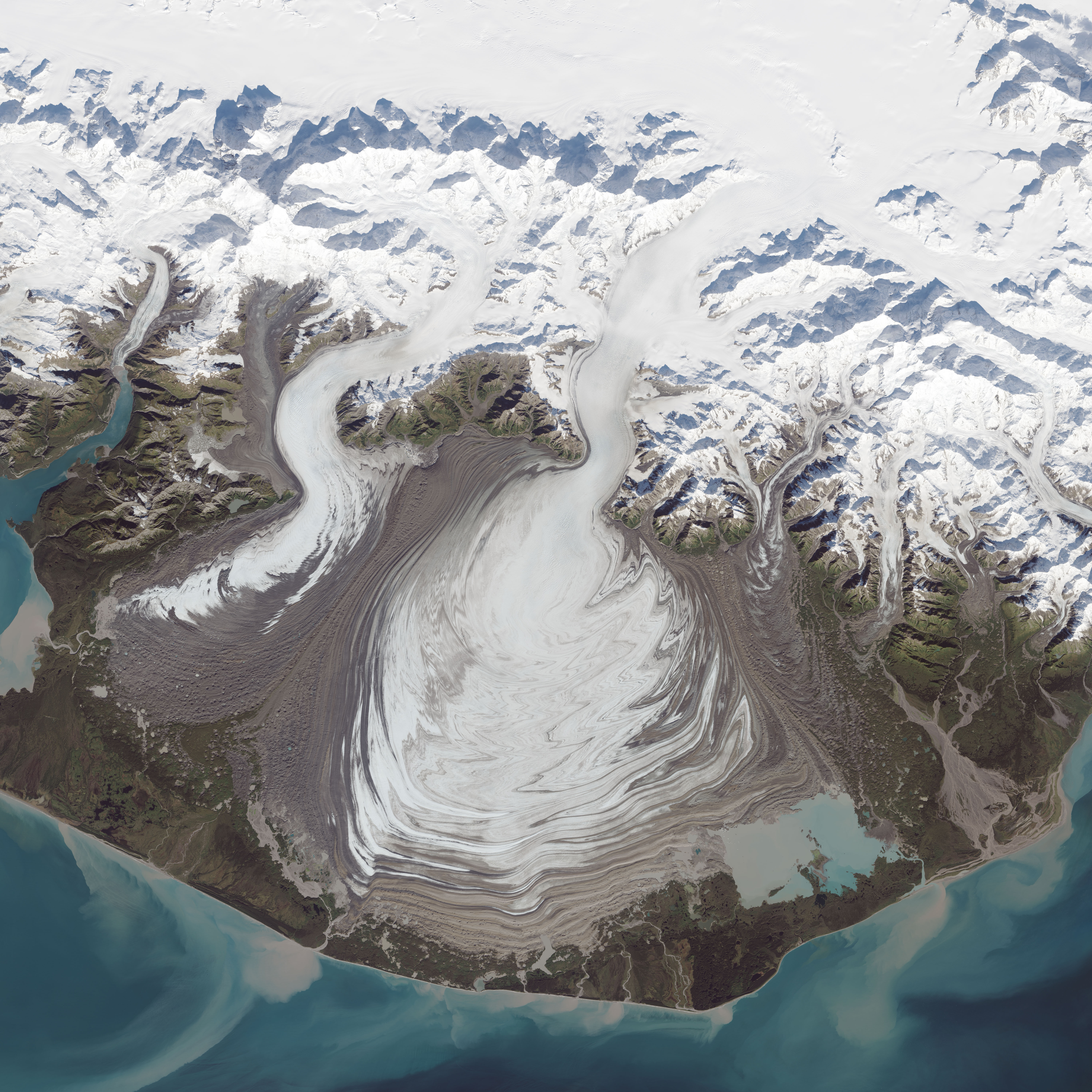

The long fade of Alaska’s largest glacier

SITKAGI BLUFFS — While paddling a glacial lake complete with icebergs and milky blue water, I dipped my left hand, then tasted my fingers.

Salty.

That was a surprise to me, thirsty there on the edge of the colossal disc of Malaspina Glacier. I was traveling with two friends, mostly on foot.

We had inflated packrafts to avoid a foot crossing of a thunderous stream outlet from the lake to the ocean. The salty water made it evident that the nearby Gulf of Alaska spills into the lake, at least at high tide and during storms.

We were floating on what scientists have named Sitkagi Lagoon. The placid body of water bordered by ice cliffs is one of many ever-growing lakes pocking the surface of Malaspina Glacier.

Someday, the power of warmish salt water will transform Alaska’s largest glacier into a blue blotch on the map, a new inlet larger than nearby Yakutat Bay.

The scientists who named the lagoon now refer to this Rhode Island-size glacier by its Tlingit name, Sít’ Tlein, which means “big ice.” In 1874, U.S. Army explorer William Dall named the dirty gray plateau hiding an expanse of ice for Capt. Alessandro Malaspina, an Italian navigator serving Spain who explored the area in 1791.

In a 2024 report for the National Park Service, Anna Thompson and Mike Loso of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve along with other authors compared the glacier’s surface to other scientists’ observations from decades ago.

“Lake numbers . . . increased from 5 to more than 200 between 1972 and 2020,” they wrote. “One of these new lakes, Sitkagi Lagoon, is ice-walled and receives input from the Pacific Ocean, portending the possible initiation of catastrophic tidewater glacier retreat.”

Vast icefields feed Malaspina its batter of blue-white ice through a notch in the St. Elias Mountains, the high ridges of which trace the border between Alaska and the Yukon Territory. Unrestrained by mountains, Malaspina’s ice oozes into its pancake shape at the elbow where Southeast Alaska bends away from mainland Alaska.

It’s hard to believe that something so big could disappear, but that appears to be happening, said Martin Truffer, a glaciologist with the Geophysical Institute of the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“It’s losing 20 to 30 feet per year in surface elevation,” he said.

The glacier has also carved its own immense, self-destructive bowl. Using radar, researchers have found glacier ice 1,000 feet beneath the level of the nearby Pacific Ocean.

“That’s kind of a bad situation to be in,” Truffer said. “Often, once retreat starts, it just accelerates. A glacier that’s on a steep slope, it can retreat back into the mountains where it’s happy, where there’s snow.”

A glacier like Malaspina (most of its ice is lower than 3,500 feet above sea level) is vulnerable to melting most of the year. Salt water eats ice even faster than mild air.

“The Gulf of Alaska has water about 7 to 10 degrees C (44-50 degrees F),” Truffer said. “As far as the ice is concerned, that’s hot.”

Malaspina has protected itself from sea water over the centuries by shoving a wall of gravel between itself and the Pacific Ocean. But the breaches into Sitkagi Lagoon and other basins are allowing salt water to seep in.

Also, the glacier’s tendency to surge — to get up and rumble forward suddenly after decades of slow movement — could someday bulldoze the earthen barrier that protects it. Malaspina has surged several times in the last half century, most recently when Truffer canceled a trip there in 2021 because the area he wished to camp upon was suddenly crevassed as the ice rumbled forward at more than 30 feet each day.

In large part due to the salt I tasted in Sitkagi Lagoon — one-third of a mile long and growing — this 1,000 square-mile lobe of ice is on the wane.

That much ice will not melt overnight. But Victor Devaux-Chupin, a graduate student working with Truffer who will soon defend his Ph.D. thesis on the glacier, said the glacier will soon start “changing beyond recognition,” with most of its incredible mass of low-elevation ice gone within the next century.