The Mechanics Of Rock-Skipping

Like any kid, I was fascinated with skipping rocks. Give me a quiet pond (actually, in my case, it was an irrigation canal) and an ample supply of skipping stones and it would keep me off the streets for hours.

I was therefore gratified to note that an article by James Trefil in the August 1985 issue of the prestigious Smithsonian Magazine takes the matter seriously. Better still, it makes reference to an even earlier article by Dr. Ernest Wright in the April 1957 issue of Scientific American.

The reason for my feeling smug about all this is that the furor is over something that I had discovered independently as a boy, but didn't recognize at the time as being worthy of such profound attention.

The observation is simply this: on a solid surface (such as the dried-out lake bed in Nevada where I did my skipping when the canal was dry), a rock hits the ground not once, but twice before soaring off on another skip. It is easy to see two scuff marks on the ground, about four to six inches apart, at every point where the rock bounces back into the air. The distance between the scuff marks seemed to be related to the size of the rock--the larger the rock, the greater the distance, but I didn't know why. I wondered if the rock also hit twice on the water. I didn't think so, but couldn't be sure.

Although my research in the Nevada desert predated Dr. Wright's observations in the 1957 Scientific American, it is only fair that he be given credit for bringing the problem to the attention of the scientific community (even if he was--of all things--head of the English Department at Columbia University). Dr. Wright admitted his shortcomings in the scientific arena, but was delighted when it developed that none of the Nobel Laureates in residence at Columbia at the time could answer the question either. With obvious relish, he wrote for the Scientific American: With the luck of a layman, I have had the novel experience of seeing several of the men who have plucked the heart out of the atom's mystery scratch their heads in vain for the solution of ... why a rock hits the ground twice when it skips." During the next decade, Wright received no fewer than 10,000 letters on the subject, none of which answered the question satisfactorily.

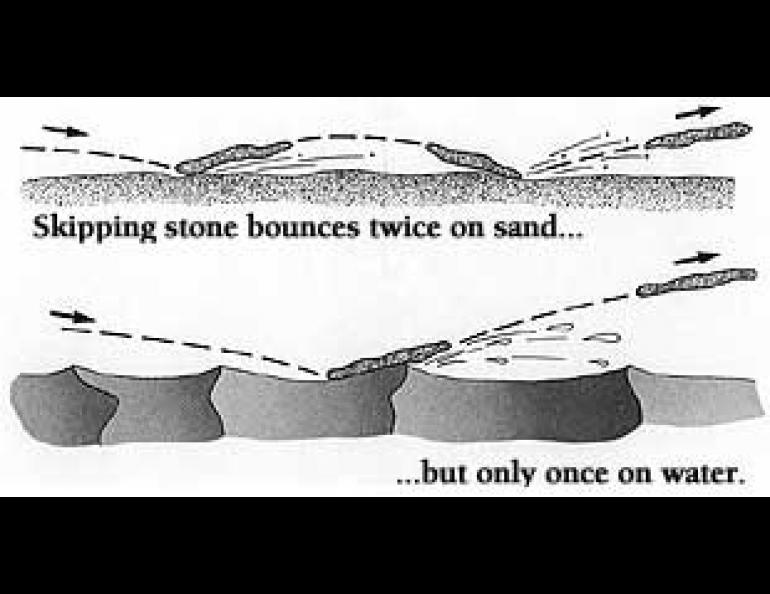

Finally, in 1967, a high school student in Connecticut came up with a solution. The student, Kirston Koths, took some high-speed photographs that showed stones ricocheting from both water and sand surfaces. It turns out that when a spinning stone comes into contact with a surface, the trailing edge usually strikes first. If the surface is hard, like packed sand, the stone tilts forward, the leading edge strikes again, and the stone takes off on the next skip.

When a revolving stone hits a fluid surface, it behaves quite differently. When its trailing edge strikes, the stone doesn't tip forward. Instead, it tilts backward, causing a small wave to build up underneath it. After planing on this wave for a short distance, the stone then takes off again without the short hop that it takes on a dry surface.