Mendenhall Glacier to pull toe from lake

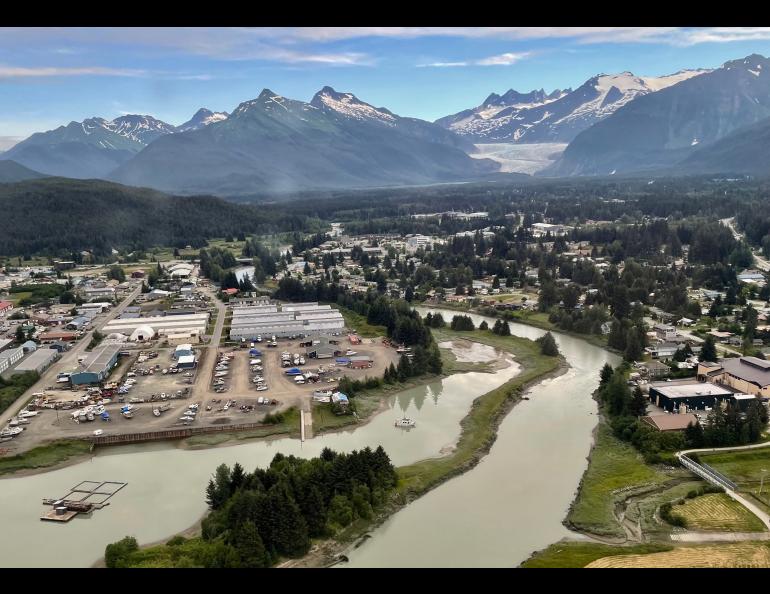

In the near future, Juneau’s Mendenhall Glacier will withdraw its icy toe from the lake of its making, scientists say.

“The lake is about to not have a glacier in it,” said hydrologist Eran Hood of the University of Alaska Southeast in Juneau. “Within the next few years is my guess.”

Hood is part of a UAS team whose members are studying glacier outburst floods from Mendenhall Glacier. He and his colleagues have been watching Mendenhall’s recent retreat from the lake, which first appeared as the glacier retreated in the 1920s.

We are close to the end of a long era of fresh icebergs floating in front of one of the most-visited glaciers on Earth.

“We’ll be able to see the glacier for several more decades at minimum, but once it backs out of the lake it’ll be climbing away from us,” Hood said. “In 2050 or beyond, it’ll be completely out of sight.”

Hood’s colleague Jason Amundson noted how the Mendenhall Glacier is part of the character of Alaska’s capital city.

“The glacier is part of the town, kind of its symbol,” Amundson, a professor at the University of Alaska Southeast, said. “There are several glaciers around Juneau, but this is the glacier.”

Native Tlingits may have called the glacier Áakʼw Tʼáak Sítʼ (glacier behind the little lake). In 1879, John Muir named this giant body of ice, which flows seaward from the Juneau Icefield, Auke Glacier. Thirteen years later, workers for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, the nation’s first scientific agency, renamed the glacier for its superintendent, Thomas Corwin Mendenhall, who helped map Alaska and its boundary with Canada.

Warming temperatures in Juneau consistent with the rest of Alaska have initiated a decades-long retreat of Mendenhall. The glacier, which spilled over much of the Mendenhall Valley during its peak in the late 1700s, has shrunk dramatically since then.

“Near the end of the glacier, the ice surface melts at 10 to 15 meters per year,” Amundson said. “There’s not enough flow coming down the glacier to replace it.”

Scientists predicted Mendenhall’s change from a lake-calving glacier to a mountain glacier as early as 2002, when Roman Motyka and his colleagues wrote that “over the next one to two decades, (Mendenhall will have) a terrestrial terminus.”

Motyka, 83, a University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute emeritus glaciologist, is a Juneau resident who has watched Mendenhall’s terminus creep toward the mountains.

“It has retreated over a kilometer since Ellie Boyce (currently with the Alaska Volcano Observatory) did her master’s thesis on the terminus in 2006,” he said.

Motyka was surprised no glaciologists had worked on such an iconic glacier in the early 2000s, when he and his colleagues received funding to study Mendenhall. Part of the impetus was the start of helicopter tours that allowed tourists to step on the ice.

One of those helicopter tour companies maintained a camp on the glacier that Motkya’s team found was set up on ice with a bed elevation below sea level. That beneath-ice basin might soon become visible.

“If the glacier continues retreating, there will be another lake (where the helicopter camp was located),” Motyka said.

For those in Juneau, Hood and Amundson will give a talk, “Researching the Mendenhall Outburst Flood: 2025 and Beyond,” on Friday, Oct. 10 at 7 p.m. at the Egan Lecture Hall of the University of Alaska Southeast.