The Return of Halley's Comet

By now, just about everybody has heard that during the latter part of this year, Halley's Comet will be making its first appearance in earth's skies since the famous visitation of 1910. How many of us have wondered since we were children if we'd be alive to see its return? But don't reserve any seats just yet--Alaska is not going to be on the 50 yard line. Sadly, this time around, it's likely that it will require a good pair of binoculars and a knowledge of just where to look in order to be able to see it at all. To understand this, it is helpful to recount what can be expected from the comet, based on observations made during its return at 76-year intervals, throughout history.

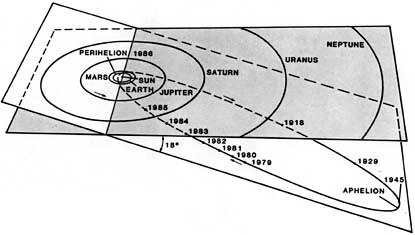

In order to visualize more easily the comet's path in the sky, we'll speak of distances in terms of the Astronomical Unit (AU). This is the mean orbital distance of the earth from the sun, about 93 million miles.

Halley's comet moves in a highly elliptical orbit, ranging from a distance of over 35 AU from the sun at aphelion (greatest distance from the sun) to just over one-half AU at perihelion (closest approach to the sun). It follows that it was last at perihelion during the 1910 appearance, and invisible from earth at aphelion in 1948. Perihelion during this orbit will occur on February 9, 1986. It is then that the comet will be at its most brilliant and will produce the longest "tail." Unfortunately, it is also then that it will be on the opposite side of the sun from the earth, and it will be invisible to viewers during the time of its greatest display.

Yet another factor will prevent the comet from being easily visible from the northern latitudes: the comet's orbital plane is tipped so that most of the path is below the ecliptic--south of the plane in which the sun and most of the planets' orbits lie. That, combined with the tilt of the earth on its axis, means that the comet will be below the horizon in the northern hemisphere most of the time. Only for a relatively short period from late November 1985 into January 1986 will circumstances combine so that the comet is near enough to the sun, near enough to the earth, and traveling high enough above the ecliptic so that it will be visible from most of Alaska. Even then it will not be spectacular, but it should be dimly visible (about as bright as a faint star) low on the southern horizon.

The comet will be above the ecliptic at perihelion, and soon after emerging from behind the sun in mid-February, it will again cross to below the ecliptic plane between the orbits of earth and Venus and be visible only to more southerly observers. As luck would have it, during the time that it can be viewed from earth, this is probably when it will be at its brightest. Comets typically exhibit more of a tail after, rather than before, their closest encounter with the sun, and the closest approach to the earth will occur after perihelion.

Unfortunately, although scientists stand to learn a great deal from their measurements and observations, there can be no escaping the conclusion that this year's visit by Halley's Comet will not be nearly as spectacular as the one in 1910. During that event, the approach to earth was much closer (0.14 AU, compared with a closest approach of 0.42 AU on April 11, 1986), and the comet was visible at perihelion. It was a worldwide sensation. Cartoonists had a field day playing on the fears of kings, Kaisers, and the common man. New products and brand names sprang up overnight, and sideshow hucksters sold "comet pills" by the handful and gas masks to ward off the perils that would ensue when the earth passed through the tail of the comet (which actually may have occurred).

It was all good fun, but not likely to be repeated this time around. For the optimist, though, there's always 2061 to look forward to.