Searching for Ancient Answers in Southeast Alaska

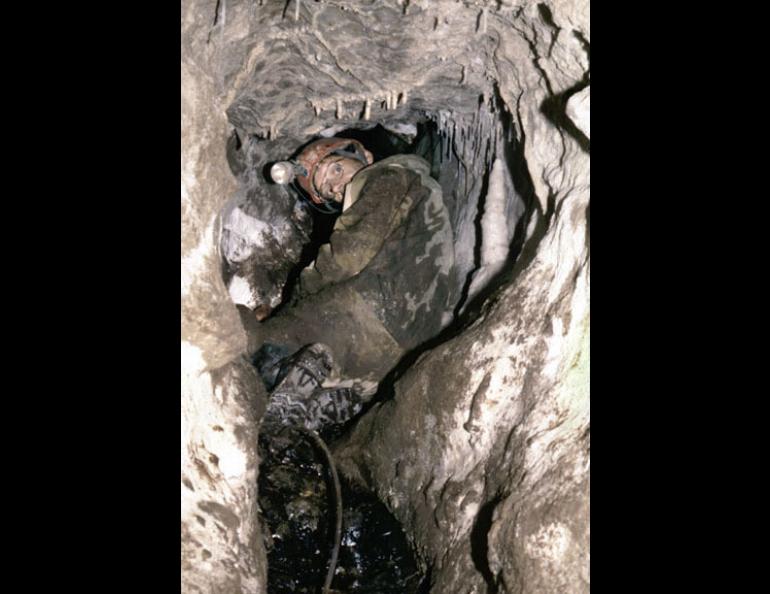

Tim Heaton has his summer plans set—crawl through rainforest caves wearing raingear and a headlamp, unearth hundreds of ancient animals, and, possibly, bump into the remains of Alaska’s first human visitors.

Heaton is a caver and paleontologist from the University of South Dakota who discovered the 9,800 year-old bones of Alaska’s oldest man on Prince of Wales Island in 1996, and the 40,000 year-old bones of black and brown bears in the same cave. The bones had a lot to say about how the first people populated the Americas and the extent of ice during the last glacial period. In summer 2003, Heaton and a team of students will explore more bone-filled limestone caves in southeast Alaska and the Queen Charlotte Islands.

The ancient human and animal bones Heaton has found in southeast Alaska support the notion that the first people in the Americas may have been boaters who skirted the huge ice sheets on land by paddling from bay to bay on what is now Alaska’s outer coast. Another popular theory is that early humans crossed the Bering Land Bridge and migrated through a narrow ice-free zone that opened up on the plains of Canada between two colossal ice sheets.

Heaton and his colleagues have dug up evidence that animals lived in Southeast before, during and after the last ice age, which lasted from about 25,000 to 13,000 years ago. The ice age was a time when glaciers covered much of northern North America, from the Arctic to as far south as New York and Chicago. Bones in the caves of southeast Alaska suggest that the ice may not have been a barrier between northern Alaska—which was not covered with ice—and the rest of North America. James Dixon, an archeologist with the University of Colorado’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, said that ancient people might have used boats or rafts to come down the northwest coast and settle in green patches amid the glaciers.

“Early humans could have used watercraft to skirt the ice along the northwest coast, dodging glaciers like recreational kayakers do today,” Dixon said.

Heaton will concentrate on animal bones while exploring the caves, but also will look for human artifacts as he and his team of five University of South Dakota undergraduate students excavate layers of bones from the caves. One of the caves they will explore is on Coronation Island, south of Baranof Island. The Coronation Island cave is unique in that ice did not cover the island at the peak of the last ice age.

“The outer island could easily have an older human record,” Heaton said. “We’ll be on the lookout for archaeological material.”

While he will seize the opportunity of finding human bones or tools, Heaton’s main focus is ancient animals. In the bone-rich On Your Knees Cave on Prince of Wales Island, Heaton found the bones of ringed seals and arctic foxes dating back to when southeast Alaska looked a lot like Barrow. The 40,000-year old bear bones suggest that bears used the cave at a time when other researchers theorize the area was buried in ice.

In addition to Coronation Island, Heaton will visit caves on the mainland across from Wrangell, Alaska, and on the Queen Charlotte Islands. In one or more of those dark limestone chambers, Heaton hopes to find out if southeast Alaska offered a refuge for animals in an otherwise frozen world.