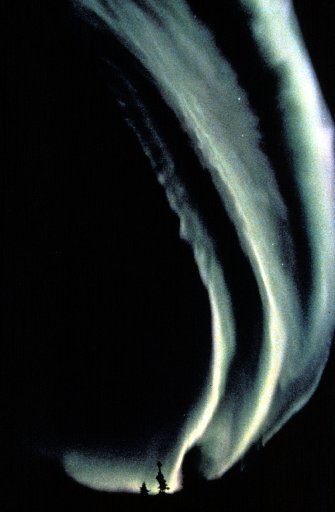

Sounds Of The Aurora

As Professor Syun Akasofu of the Geophysical Institute points out in his book Aurora Borealis, the Amazing Northern Lights, the subject of whether the aurora produces sounds can easily become a springboard for losing friendships. There are a few old-timers who insist that they have heard it, but many more long-time residents of the northland insist that this is hogwash.

As reported, the sounds usually resemble a swishing or crackling similar to that heard as waves of static on the radio. The level of intensity is said to change along with the rapidity of movement of the auroral forms overhead.

Most scientists tend to view claims of auroral sounds with skepticism for at least two good reasons. One is that, even though serious attempts at recording them have been made, none have been successful. Another is that a valid physical reason for their existence is difficult to find. Because there is insufficient air between the aurora and the ground to transmit audible sound waves, it would be impossible for them to travel directly from an altitude of 50 miles or so to an observer on the ground. At any rate, even if this could conceivably happen, the travel time would make the sound waves lag far behind the auroral movements with which they are said to be associated.

If a physical reason does exist for auroral sounds to be audible on the ground, it would most likely be due to the electrical field produced by the aurora. Power fluctuations in long transmission lines have been linked to auroral activity, and there are cases where circuit breakers have been tripped and transformers blown during highly active displays.

On the other hand, it has been suggested that it's "all in the mind" of the observer. This does not suggest that anyone who claims to have heard the aurora should be dealt with discretely and at a distance, but that the sensation of sound may actually be produced inside the head. It is not known why the electromagnetic field producing the aurora might affect the human nervous system, but most scientists do not entirely rule out the possibility that it does.

In this age of whiz-bang electronic games, most of us are accustomed to associating fast movement with some sort of sound. Perhaps the brain unconsciously adds the sound effects when a fast-moving aurora is seen. But this explanation is not very satisfying and certainly doesn't explain why the Eskimos have legends relating to auroral sounds that were told long before Pac-Man came on the scene.

Professor Juan Roederer, Director of the Geophysical Institute, counts among his many interests the physics of the brain and nervous system. He has pointed out that the brain is capable of mixing signals from the various senses before we consciously get around to interpreting what they really are. For instance, one often senses a bloody or acrid taste in the mouth when struck on the head. Roederer suggests that, in a similar manner, a signal coming from the eyes (seeing a fast-moving aurora) may be interpreted as originating in the ears.

An easy way to test this hypothesis, if you happen to be one of those who hear auroras, would be to close your eyes and see if the sound goes away.