Steaming Tailing Piles in Winter

On the still, cold and sunny days of winter, many of the long abandoned tailing piles in Interior Alaska appear to be venting something that looks like steam. This is best seen during temperatures of minus 20°F or colder, with the observer positioned to look toward the sun in the direction of the tailing piles. The dredge tailings in Fox and Ester are two prominent locations to observe this unusual effect.

Tailing piles as a geothermal source? That would be handy, but not practical in view of the tiny amount of heat being "pumped" by these miniature "chimneys" of coarse rocks. What we see, of course, is not steam, but a steady flow of (relatively) warm, moist air coming in contact with the frigid out-of-doors temperature. As the moist air quickly cools to the surrounding temperature, it is forced to give up most of its water vapor. The invisible vapor condenses into either supercooled fog droplets or ice crystals, both of which are visible on windless days under certain lighting conditions.

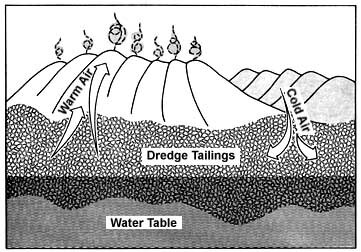

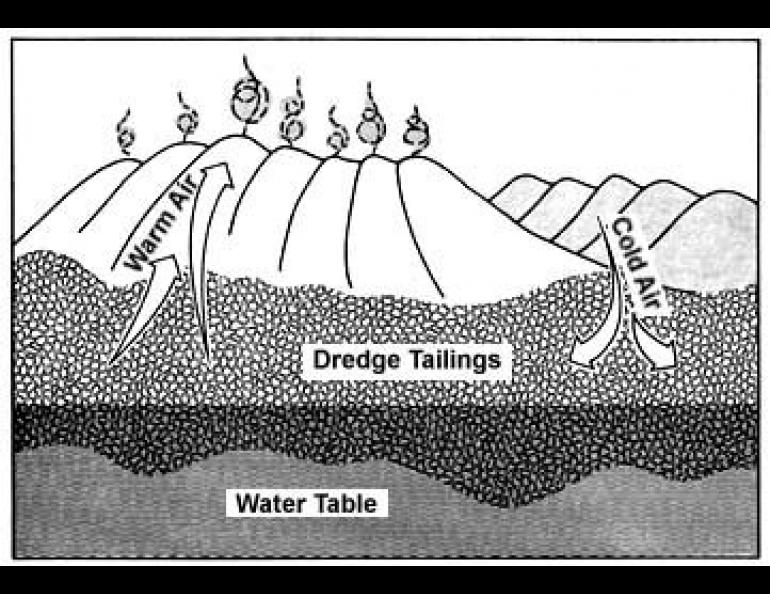

But what is the source of the constant flow of air? Is there a huge, pressurized cavern under the ground supplying a constant flow of air to the surface' Not quite. The mechanism responsible for the steady venting of water vapor is a type of heat pump. Tailings provide a volume of coarse rocks, bedded some places in the local water table, and exposed at the top to the cold, outdoor air. One characteristic of dredge tailings is a total absence of any fine material, so that a volume of these very coarse rocks encloses almost an equal amount of air which is free to circulate through the tailings.

The temperature of the water at the bottom of the tailings remains around plus 36°F even in the winter, and is much warmer than the minus 20-40°F air at the surface. The cold air at the surface is much more dense than the warmer air in contact with the water table, so the cold air tends to sink downward into the "valleys" in the ridges of tailings and then through the coarse rocks until it reaches bedrock or the water table, whichever comes first. In the process, this infiltration of cold air displaces the warmer, moist air which then moves upward toward the "peaks" of the ridges where it finally escapes, cools, and dumps its moisture.

The most active vents tend to be associated with the most discrete and tallest ridge tops, which act like "chimneys" to the convection currents of air. Sometimes miniature cones of frost cap these snowladen "chimneys" like inverted funnels, and these can force the escaping vapor into surprisingly vigorous currents of air.