The Sudden Disappearance of Mount Katmai

Mount Katmai was a handsome mountain with three peaks poking more than 7,000 feet into the moist air of the Alaska Peninsula on June 5th, 1912. Three days later, after the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century, the summit had disappeared. In its place today is an aquamarine lake rimmed by canyon walls 300 feet high. Mount Katmais transformation from mountain to crater lake is still a mystery to scientists because it imploded rather than exploded.

During the eruption that created the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, Mount Katmai collapsed into itself like an ice cream cone left in the sun. At the same time, about 10 kilometers to the west, a volcano named Novarupta spewed seven cubic miles of blistering rock and ash over the landscape. Researchers first thought that Mount Katmai was the source for most of the ash and rock that covers the valley. Other volcano craters, such as Aniakchak in Alaska, feature a vent in the crater that was the explosive source of the eruption. Later studies of the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes showed almost all the material came not from Mount Katmai, but from Novarupta. Novarupta, Latin for new vent, today resembles a crumb cake of gray rock about 1,200 feet in diameter and 150 feet high.

Geophysical Institute Professor John Eichelberger, of the Alaska Volcano Observatory in Fairbanks, recently climbed into this massive plug of lava. Thirteen others, including me, followed him up sharp, tipsy rocks and into the center of Novarupta. As we sat at ground zero on one of the worlds great eruptions, Eichelberger explained his hypothesis that the great eruption of 1912 was similar to an artesian well, with molten rock flowing from a chamber beneath Mount Katmai 10 kilometers westward to the eruption vent at Novarupta.

A large pocket of molten rock may have supported the former summit of Mount Katmai, Eichelberger said. The flow of magma, or molten rock, toward Novarupta may have been triggered by what Eichelberger calls a dike of another type of magma that rose from below to pierce and drain the foundation of Mount Katmai. All the magma may have then moved 10 kilometers west through an underground channel to explode through the surface at Novarupta. The sudden loss of its innards may have caused Mount Katmai to collapse in a fashion Eichelberger described in a guidebook he wrote about volcanic activity in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes:

One can imagine this great mountain mass shaking and cracking, with some of the debris spilling down its slopes but most of it just subsiding into a great growing pit.

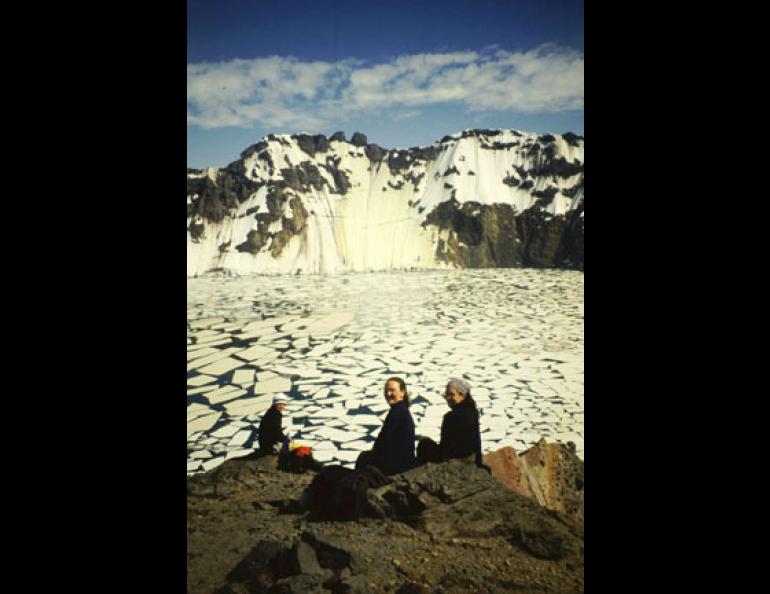

That pit, the Mount Katmai crater, is now one of the most stunning sights in Alaska. A lake more than 800 feet deep now occupies the space that used to be the inside of Mount Katmai. Three glaciers calve into the deep green water, and a 300-foot waterfall leaps from the west wall of the crater.

The lake within the crater was rising in the 1970s, but scientists havent measured it since. If its still rising, the water could spill out of the rim of the crater, quickly erode the fragile lip of rock and cause a flood that could carry boulders the size of houses. Similar floods happened at two other Aleutian Island volcanic craters, Aniakchak and Okmok. But the crater walls may be leaking as much rainwater and snowmelt as the lake is gaining, and the life of this spectacular body of water is tenuous to begin with. In the middle of a lineup of volcanoes that stretches to Russia and beyond, Mount Katmai will probably force mapmakers to redraw its summit yet again.