Taking a walk through time

As I start a walk through time, the sun is shining in Fairbanks and a warm breeze touches my cheek. Each step I take represents one million years in the history of Earth; by the time I walk back to my office, I’ll have covered one mile and 5 billion years.

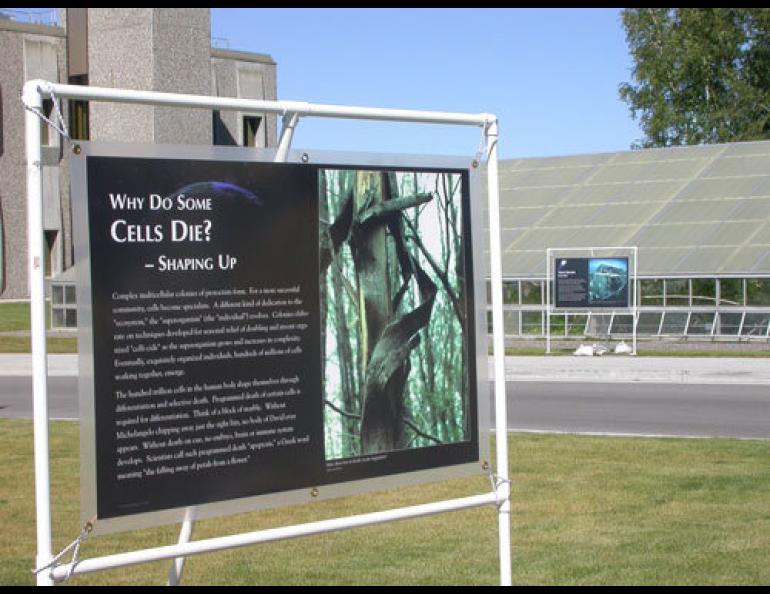

I’m checking out an exhibit of 90 museum-type panels standing outside in a somewhat linear mile on the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus. A professor of natural resource planning, Susan Todd, brought the national exhibition, called “Walk through Time . . . From Stardust to Us” here, and installed the panels with the help of the Quintal family. Part of Todd’s goal is that people taking the walk would gain “a concept of the immensity of time.”

Off I go, starting at UAF’s Wood Center. There I bump into atmospheric scientist and curious person Glenn Shaw, who has just passed the panels going the other way.

“It’s pretty humbling to think of every step you take as one million years,” he says.

He walks on, gaining millions of years on me as I pause across from Kobuk Drive to read about the formation of Sun and Earth about 4.6 billion years ago.

Ten minutes later, I learn about how the oldest mineral crystals on Earth, zircons found in western Australia, date back to 4.3 billion years ago. I’m standing across from Skarland Hall, where I lived as a UAF student in 1986. The blip of time since then is a fraction of an inch on this walk.

Twenty minutes have ticked away by the time I reach the Yukon Drive overlook of the sharp white peaks of the Alaska Range. Here, the panel representing 3.3 billion years ago describes how the exhalations of microbial life on Earth developed an atmosphere unlike that of Mars or Venus, one that allowed for the development of the fragile species known as us.

After walking and pausing at the displays for a half-hour, I’ve reached the UA Museum of the North, still under construction with the whine of power saws eating through sheet metal. The Walk through Time is like being in an outdoor museum; it’s a pleasant experience on a day like today, made possible in part because of the ultraviolet-ray blocking power of ozone, which developed above Earth 2.1 billion years ago.

With one hour and three-quarters of a mile under my sneakers, I’m on UAF’s West Ridge, where a poster standing in front of the Irving Building represents 800 million years ago, when Earth’s first ice ages trapped much of the world’s water in ice. Above, swallows feed their squeaking newborns in mud nests under the cement eves of the Irving Building.

I’m still 540 million years away from the present as I reach the Geophysical Institute and the International Arctic Research Center. A panel there informs me that “ . . . fossil traces (furrows and burrows) recorded our distinguished, flexible ancestors—the worms.”

After running out of sidewalk in its quest for a straight mile, the timeline bends eastward toward the Arctic Health building. Panels are crowded together here, reflecting a relative wealth of knowledge about recent periods.

I’ve been walking an hour and 20 minutes and have advanced to 65 million years ago, when an asteroid six miles in diameter banged into Earth and “all animals over 55 pounds disappear, including the beloved (dinosaurs).”

After an hour and a half, I’ve reached the last panel. About five feet from the end of my mile, I get to the point where “Homo sapiens sapiens spread over the world, entering North America through the Bering land bridge.”

To cap off the experience, which to me is striking in that it shows how much and how little we know about the planet, I see a final graphic. On the time scale I’ve been walking, the human population on this blue and brown sphere has increased from zero to near six billion in the last quarter inch.

The "Walk Through Time . . . From Stardust to Us" exhibit will reappear on the UAF campus on Sept. 6, 2005. This column is provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community.