Voyage of the Manhattan

Ever since Christopher Columbus stumbled upon the American land barrier separating the Orient from western Europe, it has been the goal of explorers to find a shortcut around this pesky continent that would provide a lucrative trade route between the East and the West. Thus began the search for the fabled "Northwest Passage," although nobody knew if it even existed.

Such famous names as Jacques Cartier, Sir Francis Drake, Sir Martin Frobisher and Captain James Cook all met with failure. Some met with disaster. Sir Humphrey Gilbert drowned during an attempt in 1583. In 1611, Henry Hudson, his young son, and seven others were set adrift by a mutinous crew when his discovery of Hudson Bay proved to be an icy trap instead of the passage he sought.

The worst tragedy came when Sir John Franklin and 129 men aboard HMS "Erebus" and HMS "Terror" vanished in 1845.

There are many other examples of failures and catastrophes in the search for the Northwest Passage.

In 1850 Sir R. J. McClure sailed eastward from Bering Strait in the "Investigator" but was forced to abandon it on Banks Island in 1853. He walked to Melville Island with his crew where they there joined the "Resolute" which was also later abandoned and the combined crews returned to England on Sir Edward Belcher's "North Star". McClure received a prize of 10,000 English pounds for his discovery of the Northwest Passage. Roald Amundsen in the "Gjoa" traversed the Passage from east to west starting in Norway in 1903 and arriving in Nome in 1906 to become the first expedition to transit the entire passage in one ship.

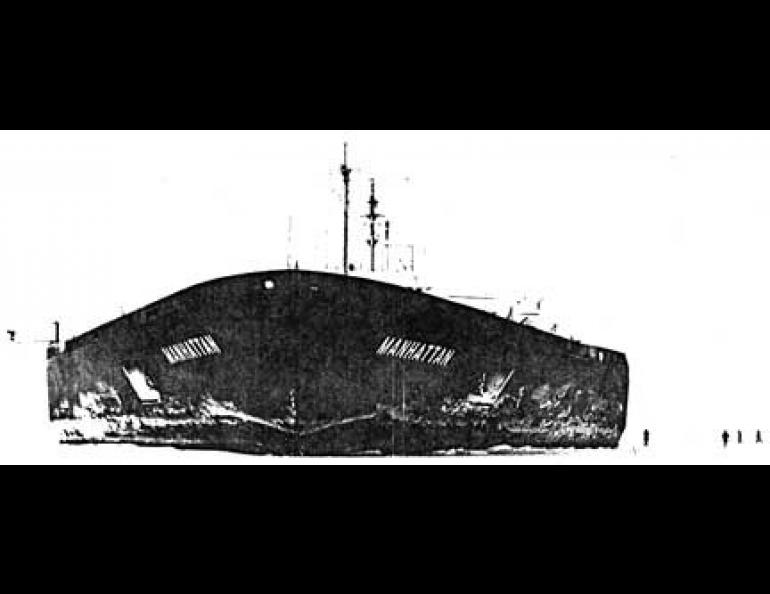

In 1969, a hot issue was the question of how to best transport oil from the recently confirmed fields of the North Slope to markets further south. Although it is history now, the pipeline option was chosen, and it was deemed unfeasible to utilize the Northwest Passage for oil transport by tanker. This decision was arrived at largely through the experimental voyage of the Manhattan, the largest and most powerful commercial ship ever built in the U.S.

The Manhattan, heavily reinforced for this voyage, was as long as the Empire State building laid on its side, and displaced about twice the amount of water as the Queen Elizabeth. She was equipped with the latest nautical navigation aids, relying largely on satellite fixes which could place her location to within a third of the ship's length. These instruments did not always work, however, and at times it was necessary for the crew to measure the ship's speed by throwing blocks overboard and timing their passage by stopwatch.

Setting sail from Chester, Pennsylvania on August 24, 1969, she managed to plow her way north to Point Barrow by September 14, and returned to New York by November 12.

But there were problems. Although the Manhattan broke ice up to 14 feet thick for extended periods and smashed ice ridges up to 40 feet, she often got stuck in hard polar ice.

Apparently underpowered in reverse, she had only one-fourth as much power to go astern as to go forward. At one point on the night of September 10-11, the Manhattan was attempting to become the first vessel to make an east-to-west passage of McClure Strait when she became locked. She escaped only when steam was diverted from heating the living spaces to squeeze an additional 7,000 horsepower from her 43,000 horsepower turbines. Even then, it was only with the assistance of her constant companion, the Canadian icebreaker, "John A. McDonald," that she was able to escape. The U.S. Coast Guard ship "Staten Island" also assisted in the effort.

Although the Voyage of the Manhattan may have demonstrated that the Northwest Passage may never be feasible for commercial ocean traffic, nuclear-powered submarines use it routinely. Many lessons were learned that may eventually lead to the construction of vessels twice her size. In addition, there were scientific experiments carried aboard that, in time, should more than compensate for this audacious undertaking.