When the Gobi Desert Visited Alaska

A windstorm in the Gobi Desert recently sent a wake-up call to two Alaska scientists. At 2 a.m. on April 12th, the cell phones of two volcanologists in Anchorage began to ring, a sign that tiny particles the size of volcanic ash were floating in the air above Cleveland Volcano in the central Aleutian Islands.

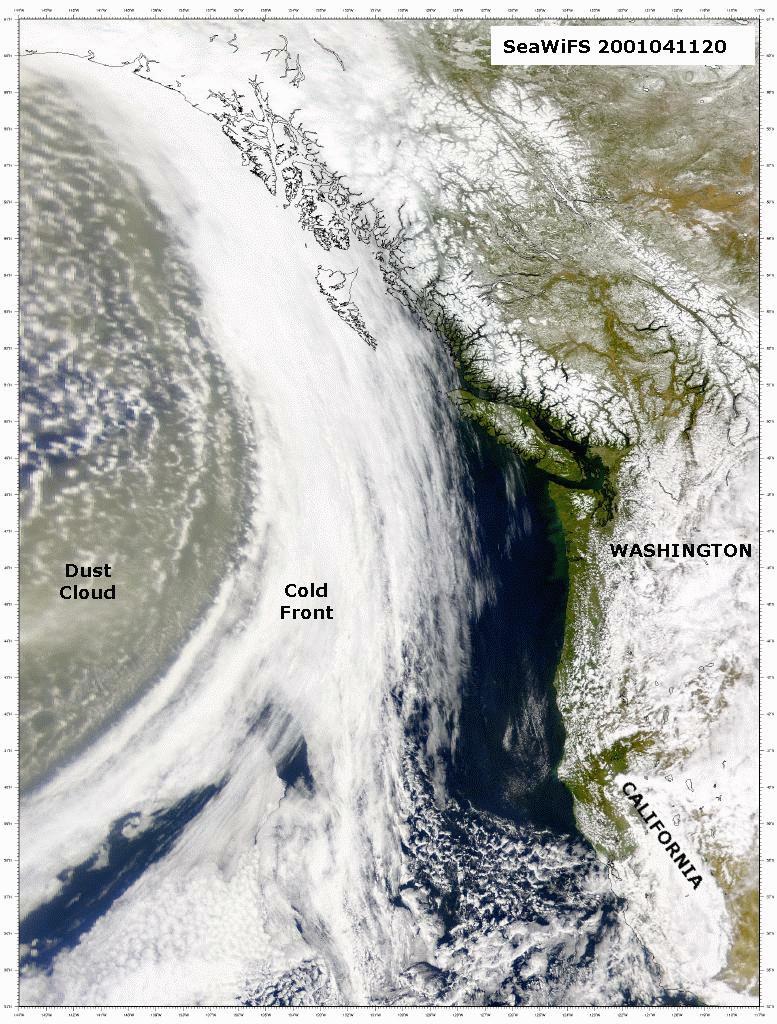

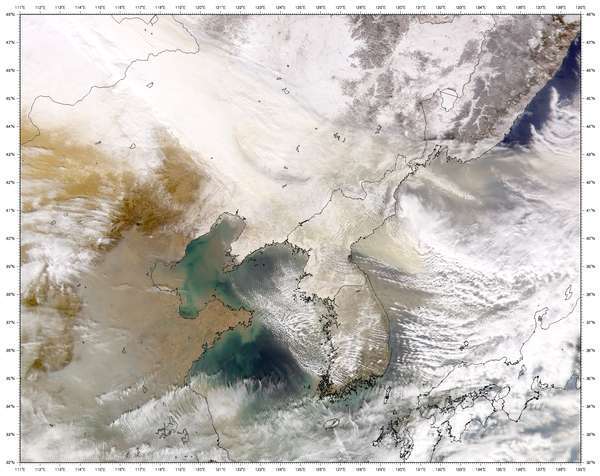

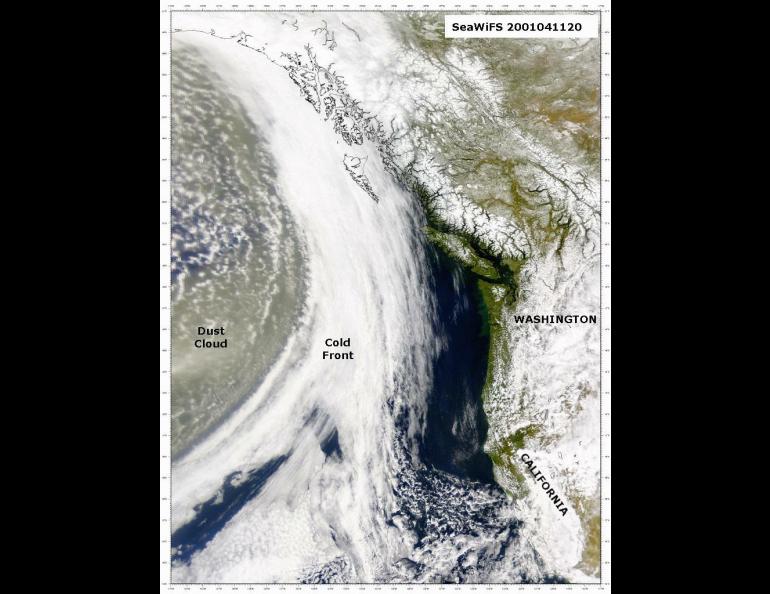

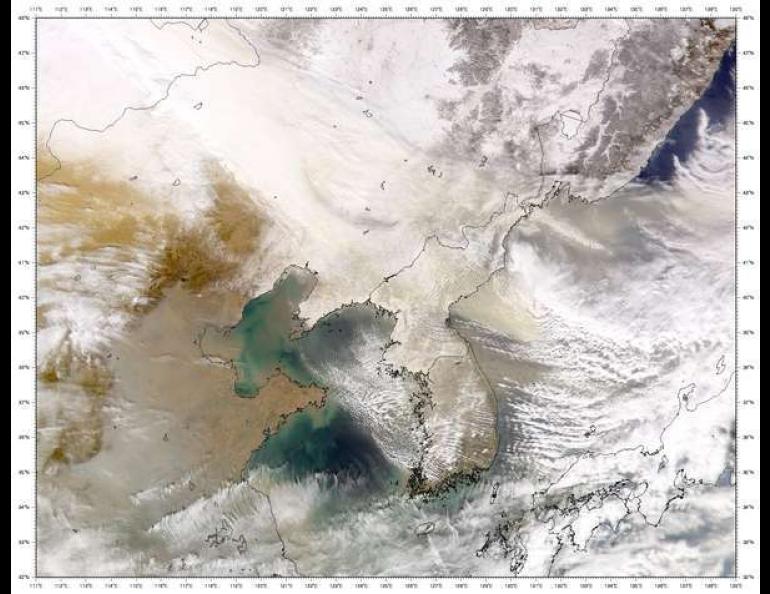

The cell phones of these scientists, on-call members of the Alaska Volcano Observatory, were linked to satellites that detect volcanic ash in a buffer zone around Cleveland Volcano, which first erupted on February 19. Dave Schneider, who works for the observatory, tracked the mystery cloud back to its source using another satellite signal. He discovered it was a now-famous dust cloud born in the Gobi Desert in eastern Mongolia and the Taklimakan Desert in western China.

A few days later and a bit farther north, atmospheric scientist Glenn Shaw looked southward from his office window at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and noticed a milky haze where there should have been mountains. "The Alaska Range was just obliterated," he said.

Shaw, who studies Earth's atmosphere at the Geophysical Institute, can identify the usual culprits when the Alaska Range disappears from view. Glacial dust whipped up by local winds, fire smoke, and arctic haze-pollution from Asia and Siberia that visits in the spring-can all wipe out distant views when tiny particles in the air scatter light. But this haze was a little different, a bit more yellow than usual.

Shaw and Cathy Cahill, an atmospheric chemist at the Geophysical Institute, tracked Alaska weather patterns back a few days and found that the particles hiding the Alaska Range came from Asia. Then, they checked the filters of an air-sniffing device installed about 33 miles north of Fairbanks. There, on clear sticky film 5,000 miles from home, was yellow-brown dust from the great deserts of Asia.

The massive dust cloud that reached Alaska started as powerful winds that swept up millions of tons of debris from deserts in China and Mongolia. The dust became a cloud the size of Japan that weather systems carried around the globe, sometimes as high as seven miles above the ground. Winds caused by a low-pressure system in the Aleutians may have siphoned off some of the dust and carried it to Alaska.

The dust's long journey highlights how small the world is. For 25 years, Shaw has studied arctic haze, which descends on Alaska during the spring because of unique weather patterns. Though arctic haze has been decreasing lately, perhaps due to the breakup of the Soviet Union and the reduction in factory emissions, Shaw thinks pollution from China will increase as it becomes more industrialized. "Asian dust can be mixed in with considerable amounts of pollution from China," he said. "And it's just going to get worse." Dust from the recent cloud has been impressive in its longevity. Those tracking the dust cloud say particulates from the storm can orbit the planet once before gravity finally pulls them from the sky. The dust from this particular storm has now settled all over the planet, which means that tiny grains of sand walked upon by Genghis Kahn may now rest in a spruce bog near you.