Fast-moving Greenland glacier has the attention of UAF scientists

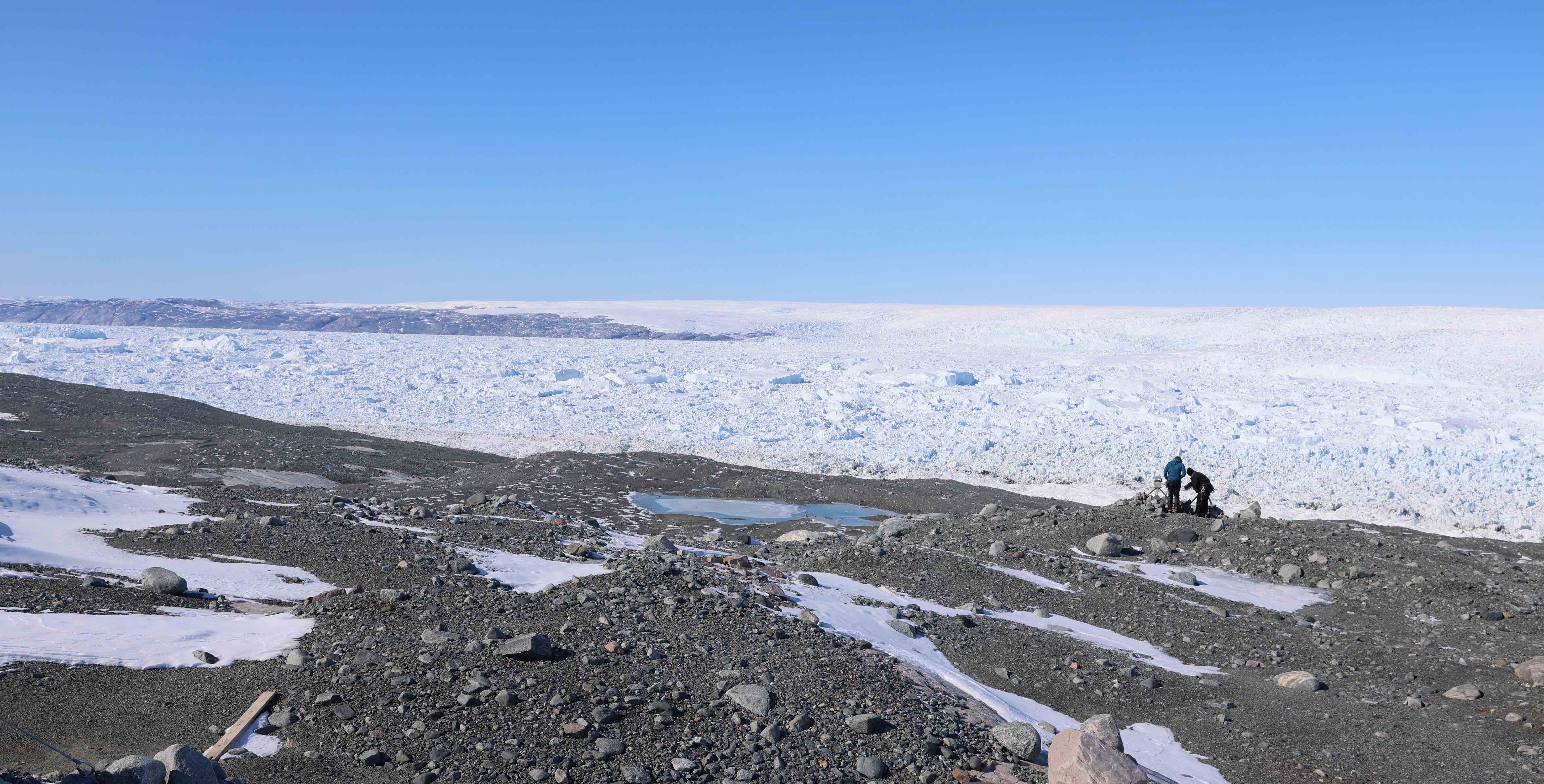

A powerhouse of ice flows rapidly on Greenland’s west coast, heading toward the ocean. Some of Earth’s largest icebergs are produced here, tumbling from the tip of Jakobshavn Glacier.

Jakobshavn is one of Earth’s fastest-moving glaciers and one of the Greenland Ice Sheet’s largest glaciers. It produces about 10% of Greenland’s icebergs.

It is also rapidly retreating.

“We don't have a good handle on how quickly this glacier could move in the future or whether there is some sort of speed limit,” said Martin Truffer, a University of Alaska Fairbanks physics professor.

Visit our StoryMap format of this story to see videos, including a time-lapse video of the glacier's movement.

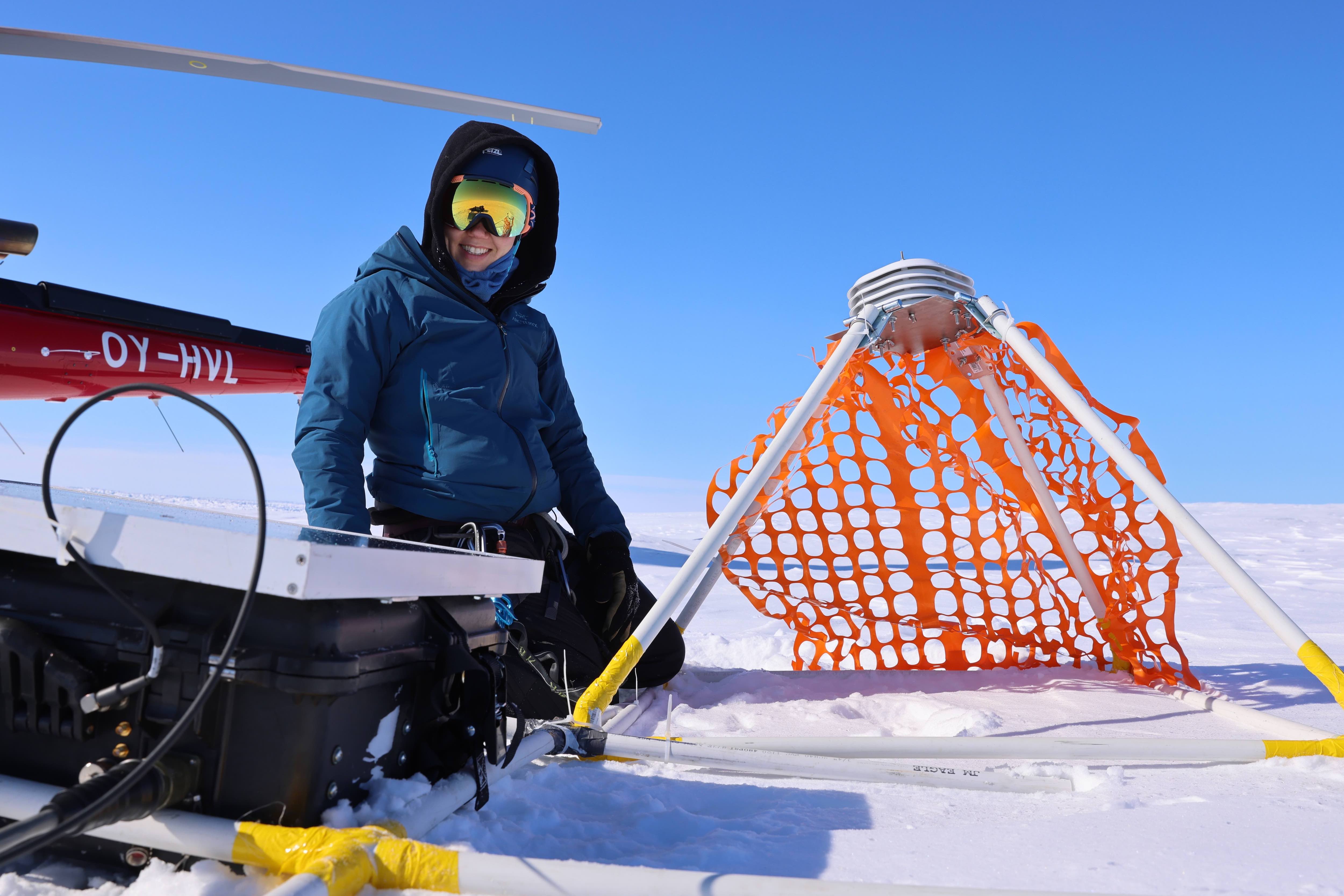

Truffer, who specializes in glacier dynamics, and UAF Geophysical Institute graduate student researcher Amy Jenson returned earlier this month from their second trip to Jakobshavn, where they are studying how meltwater and the ocean affect the glacier’s ice loss.

“This is important, because these fast-moving outlet glaciers are the main mechanism for the ice sheets to shed ice into the ocean,” Truffer said. “The mechanisms of fast glacier flow and how it varies are still not sufficiently understood.”

The glacier has retreated about 25 miles since 1850, with the most significant changes occurring since the late 1990s. It briefly advanced from 2016 to 2018 due to cooler ocean waters but has since resumed its retreat.

Jakobshavn, whose Greenlandic name is Sermeq Kujalleq, is one of the most significant contributors of glacial melt to global sea level rise. It drains about 7% of the Greenland Ice Sheet and has produced some of the Northern Hemisphere’s largest icebergs.

Truffer and Jenson placed 12 GPS units on their latest visit. They placed time-lapse cameras at the glacier front in 2024.

“GPS helps us measure flow on short time scales, from less than a week down to hours, which are time scales not currently accessible by space-based observation,” Truffer said. “Runoff can affect ice flow within hours, so we need high time resolution to document that.”

The GPS units, some accompanied by weather instruments, were placed on the north, central and south branches of the glacier because they represent the main three flow paths toward the terminus, Jenson said.

“The sites we chose are also far enough from the terminus that the surface is smooth enough for us to land the helicopter, deploy the instruments and be able to recover them in the fall,” Jenson said. “Stress is high close to the terminus, and the surface is too crevassed to deploy our instruments.”

Data from the four-year research project, funded by the National Science Foundation, will improve computer models used to forecast glacial ice loss.

The project includes creation of a museum exhibit about tidewater glacier change in Alaska and Greenland. The researchers are working closely with the University of Bergen, which operates a Science and Art Center in Ilulissat and with the Ilulissat Icefjord Center.

The exhibit, still in planning, will appear first at the University of Alaska Museum of the North in 2026.

The research project’s principal investigator is Lizz Ultee, an associate research scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and Morgan State University in Maryland. Also involved is geophysics professor Jason Amundson of the University of Alaska Southeast. Amundson was Truffer’s first doctoral student and studied Jakobshavn Glacier for his Ph.D.

Jakobshavn has become a glacier of intense research interest. Its sensitivity to ocean temperature changes offers critical insights into how warming seas affect ice sheet dynamics and coastal stability.

And that draws the pair of UAF researchers.

“Watching the time-lapse video was incredible,” Jenson said. “After being there in person and watching the video, I could see just how far the glacier terminus moved over the year and how much ice was discharged into the ocean.”

“I’m used to seeing Alaska glaciers, where changes on this scale take place over many years, not months,” she said. “The scale of the glacier and the changes in terminus position seem big on paper or in satellite images, but seeing them in person is far more impressive. “

Jakobshavn even leaves a mark on a veteran glaciologist like Truffer. As a glaciologist for 30 years, he has traveled to glaciers in Europe, Asia, North and South America, Antarctica and Greenland.

“Fast flowing ice has always fascinated me, things like surging glaciers and tidewater glaciers,” he said. “Jakobshavn is a really rapidly changing glacier, so seeing the landscape changes on this scale is really impressive.”

• Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu