Research straightens out what caused the arc under Alaska’s mountains

Two related major tectonic processes that occurred simultaneously 75 million to 50 million years ago created the grand arc on which three Alaska mountain ranges sit today, according to new research by a University of Alaska Fairbanks scientist and others.

The research links fault movement on the far northern reach of North America, which was split by a seaway at the time, to the forces that also caused a tectonic plate collision that added material to the south on that landmass.

The concurrent actions led to the curvature seen today in the arc of the younger Alaska Range mountains, Wrangell Mountains and St. Elias Mountains.

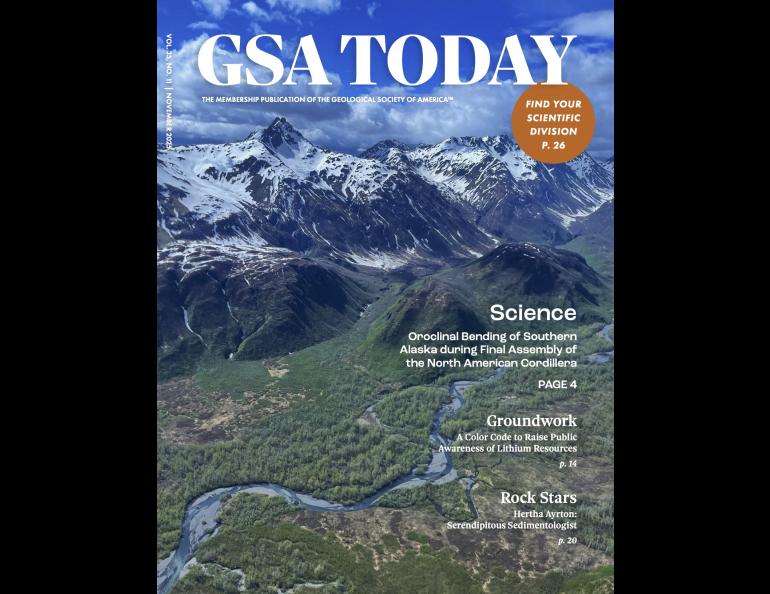

The work by UAF geology professor Sean Regan and two colleagues at other institutions was published on the cover of the November edition of the Geological Society of America magazine GSA Today.

It provides a new and definitive understanding of how forces bent the ancient edge of the North American continent into what is now Alaska.

The findings result from new and precise dating of ancient geologic events in Alaska and western Canada. Scientists have been investigating the curvature’s cause since at least 1955.

“One of the difficult things in Alaska is that it’s so big and has so many different geologic things that have happened over its history that it’s difficult to develop a causal relationship between processes,” Regan said. “Our work brings together a lot of the large-scale observables and explains them.”

The three mountain ranges constitute what geologists refer to as the Alaska orocline, a folded mountain belt.

The Alaska orocline is part of the Alaskan-Canadian Cordillera, which is part of the North American Cordillera, a string of connected mountain ranges running from Alaska to Mexico. That cordillera is part of the longer chain of mountains that concludes at the tip of South America.

“The edge of the modern Alaskan-Canadian Cordillera went through a lot of changes between 75 million to 50 million years ago,” Regan said.

What was happening?

Curved mountain belts are common around the world and are closely tied to tectonic plate subduction. Alaska’s curved belt is different, as it doesn’t involve one plate sliding beneath another. Millions of years ago, Alaska, like the rest of Earth’s surface, didn’t look much like it does today. Instead, the land that would become Alaska was the northward-pointing tip of a long and slender north-south landmass. It was separated from the rest of North America by a seaway.

Regan and his colleagues write that large crustal blocks at the northern end of the slender landmass began sliding past each other on major strike-slip faults, where two blocks move past each other like cars moving in opposite directions on a highway.

They also determined that additional crust attached to the landmass’s western edge farther south at the same time.

The added crust collided with the western edge of the young continent at an angle, simultaneously pushing in while sliding northward. That helped build the coastal mountains of today’s Alaska and British Columbia.

The combination of the northern fault action and the southern land accretion instigated the counterclockwise rotation at the top of the slender landmass, the researchers report in their November publication.

The rotation would bend and stretch the largely straight mountainous region to create Southwest Alaska and the eventual Alaska orocline of the Alaska Range, Wrangell Mountains and St. Elias Mountains, they write.

“We know that 80 million to 100 million years ago the cordillera was much straighter,” Regan said. “Trying to understand when and how it developed and the actual physical processes causing it or driving it is a large-scale question that wasn’t resolved.”

How they did it

The researchers began by looking at paleomagnetic data from 31 sites in western Alaska to figure out how the crust there has rotated through time.

Paleomagnetism studies the magnetic field recorded in rocks at their formation to understand how continents and crustal blocks have moved over time.

Geologists can calculate how much a landmass has rotated by comparing the magnetic declination of a site’s dated rock samples with the site’s present-day declination. Magnetic declination is the variance in degrees from geographic north.

They then compared the Alaska rotation and its dates with what has been known about the evolution of the coastal Alaska and British Columbia mountains, where land was being added, during the same period.

That showed a clear time association.

“Alaska had been rotating in a counterclockwise fashion from 75 million years ago to approximately 55 million years ago,” Regan said. “Evidence of that is preserved in the paleomagnetic record.”

The big picture

The new paleomagnetic analysis shows the events were part of a broader regional reshaping driven by the currents of the liquid mantle, the sinking of oceanic plates and the push from the formation of new ocean crust as molten rock rises.

“We feel there is a causal relationship that helps us understand the development of the southern Alaska margin from the Cretaceous to the Cenozoic,” Regan said.

The lead author is Trevor Waldien of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. Bernard Housen of Western Washington University is another co-author.

• Sean Regan, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, sregan5@alaska.edu

• Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu