Research provides details of possible NASA moon landing sites

A University of Alaska Fairbanks postdoctoral researcher has helped NASA better understand two of the possible landing sites for the space agency’s Artemis program, which aims to land humans at the moon’s south pole and establish a sustainable base camp there.

Planetary scientist Indujaa Ganesh assisted in the research of sites known as 007 and 011 on opposite sides of the lunar south pole prior to joining the UAF Geophysical Institute, where her focus is Venus and Mars.

“The reason for being interested in the south pole is that prior research has suggested that it contains water ice and that people will be able to access it when they get to the south pole,” Ganesh said.

Research about the two sites was published Sept. 28 in The Planetary Science Journal. Nandita Kumari of Stony Brook University in New York is the paper’s lead author.

The research occurred in 2020. Ganesh was involved as part of an internship program at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas. The program is supported by funding from the LPI and the NASA Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute at NASA Ames Research Center.

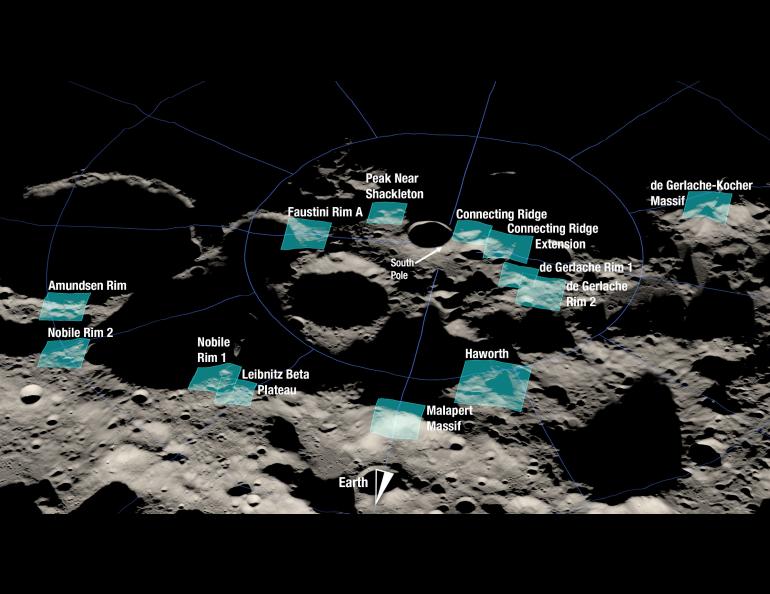

NASA was considering six Artemis landing sites at the time but in August of this year announced 13 possible Artemis III landing regions, each about 86 square miles and with multiple potential circular landing sites of about 650 feet diameter.

Artemis III is to be the first of the Artemis missions to put astronauts on the surface at the lunar south pole. Artemis Base Camp would be established after Artemis III and built up incrementally in subsequent robotic and human missions.

The six proposed landing sites, including sites 007 and 011 that Ganesh helped investigate, are within the 13 regions NASA announced in August. Site 007 is located in the region shown as "Peak Near Shackleton" on the new list, and site 011 is within “de Gerlache Rim 1.”

Site 007 sits between the 13-mile diameter Shackleton Crater and the even larger Slater Crater, which has a diameter of 15.6 miles. Site 011 is on the rim of de Gerlache Crater, which has a diameter of 20.3 miles.

The south pole is an area of extreme topography, with summits of approximately 7,500 feet above lunar datum, the moon’s equivalent of sea level, and crater floors of approximately 14,000 feet below, according to the research paper.

Ganesh and her colleagues on the 2020 research team considered several factors: likely presence of water ice and other resources, amount of illumination, geologic factors such as terrain age and slope, and suitability for scientific needs.

Illumination is key because surface operations near the south pole will rely on solar power. Both sites are illuminated about 80% of the time, sufficient for operations.

“When we're looking at these sites, we're trying to understand how much of each site will be illuminated over the course of the mission duration,” Ganesh said.

Terrain analysis is also important.

“If you are an astronaut on the surface, with or without a rover, are the places for exploration accessible?” she said. “Are you going to be in dangerous terrain? Are you going to be able to operate your vehicle or walk around safely and be able to collect those geologic samples?”

Another major consideration is availability of lunar resources, particularly water ice.

Sites 007 and 011 are elevated, allowing for ample illumination, but are also near permanently shadowed regions, or PSRs. Those regions are believed to hold water ice and other frozen volatiles such as ammonia and methane. They are also only a few degrees above absolute zero, which is minus 459.67 degrees.

“The focus was on finding places that have enough sunlight to carry out surface operations but which are still close enough to a permanently shadowed area where astronauts can potentially find water ice and make use of it,” Ganesh said.

They also looked at the mission possibilities within 1.2 miles and 6.2 miles at each site, with the larger area based on astronauts having a vehicle.

Artemis III, to launch in 2025 or 2026, will put two astronauts, including the first female astronaut, on the moon’s south pole for about one week.

Artemis I is an uncrewed test mission scheduled to launch this November, orbit the moon for about six days and return to Earth. Artemis II, to launch in 2024, will be a test flight carrying astronauts and orbiting the moon.

NASA’s Artemis program will use commercial payload systems to deliver several science instruments to the moon. International partners are providing various components of the Gateway lunar orbiting space station that will support surface operations. A robotic rover the size of a golf cart will be sent to the moon in 2024 to search for water ice prior to Artemis III.

The Artemis program will provide testing opportunities for NASA’s plan to send humans to Mars in the 2030s. NASA calls this its Moon to Mars program.

Indujaa Ganesh, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, iganesh@alaska.edu

Rod Boyce, University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, 907-474-7185, rcboyce@alaska.edu